The Divine in the Connubial Paradigm

By Smita Mukerji

Not too far back there was a series of calumnious tweets on the Rāmāyaña by Audrey Truscke, an author of questionable scholarship and dubious connections, who has built her fame doing hit jobs on Hindus and airbrushing historical crimes against them, that once again lays bare the inveterate antagonism that the Abrahamic cults harbour towards naturalistic traditions like Hinduism and seek to destroy it through ceaseless assaults directed towards it. This hostility in case of Christianity has only changed form, from cruel inquisitions and genocidal campaigns of the past centuries to a war of elaborately contrived sophistry to coerce a narrative bound to their predications and suitable to the interests of the Christian world.

But other than the fact that the recent bit of scurrility calls attention to such repeated bids at imposing a certain ideological framework by fitting a timeless literary work into themes of oppressive patriarchy and suffering feminity, Truschke’s spurious claims merit little more of our time, repudiated as these have been thoroughly by several reasoned voices in social media, the ones she is wont to promptly label as “Hindutva trolls” and block the moment her bluff is called. What is far more worth our while is to deepen our own understanding about some of these aspects of the epics which appear troublesome when assessed against modernist ideas. One such episode is the agniparīkśā in the ‘Yuddha Kāṇḋa’ of the Rāmāyaña.

Today is ‘Sītā Navamī’, the day the Goddess Lakśmī is said to have incarnated to unfold the divine play of Nārāyaña in the Trētā Yuga conjoint with the avatāra of Śrī Rāmaćandra. Their eternal story remains imprinted on the psyche of this land as the exemplary humans of their age worthy of emulation, love and reverence.

“The world idea [of the time] is a glorious androgyny. Complementarity is its underpinning. Compliments on the consummation of the praxis in complementation are reserved mostly for her [Sītā].”

If one has read the Vālmīki Rāmāyaña, one would know that Rāma did not ‘put Sītā through a trial by fire’ as is the common refrain in revisionist versions. The narration in the epic is thus: As Jānakī approached Śrī Rāma, he assumed a rigid countenance and said to her, that he had acted in accordance with his manly dharma in freeing her from the oppression she was suffering and cleansed the blemish on his lineage. But there was a doubt cast on her character as she had resided in another man’s house and having her in his power he would have molested her. And therefore Rāma said to Maithilī that she was free to go wherever and with whomsoever she wished, but he was unable to accept her back. Struck with grief at these harsh words, the mortified Vaidēhī addressed Rāghava through her tears saying that his behaviour was that as of ordinary men who cast aspersions upon the conduct of ordinary women and thereby cast doubts on entire womankind. She berated him for being a feeble man who had disregarded his wife’s devotion and virtues. Greatly distressed and immersed in thought, Sītā then commanded Lakśmaña to prepare the fire, as that was the only medication for the calamity that had befallen her, having suffered a false accusation, and the only destination of those who had no destination, since that was her predicament abandoned in an assembly of people by her beloved.

The scene is a metaphorical representation of the judgement women must go through in the world every day. Śrī Rāma assumed a stern exterior because he knew Sītā would have to go through it. Mother Sītā went through agniparīkśā on her own volition. In spite of Lakśmaña’s furious protestations, Sītā and Rāma were firm and one in their decision. Because they both knew.

It is clear from the narration that this episode addresses the inferior, lowly minds that assail the character of women and would have done so even with Sītā and not considered her a dēvī fit to be worshipped alongside Śrī Rāma. Don’t some perverted minds still do so, allege that Sītā had been ‘raped’ by Rāvaña? It is to silence the baser thoughts of humanity and not to satisfy the ego of Rāma as a common male that the agniparīkśā episode is incorporated in the Rāmāyaña.

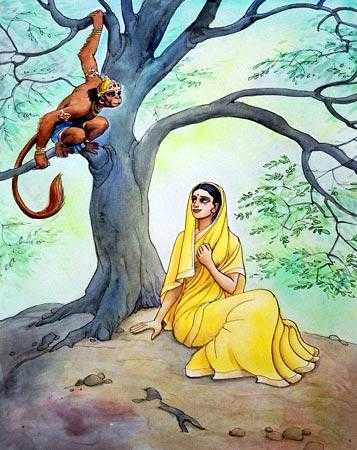

Sītā and Śrī Rāma are the ultimate complementing partners who support each other’s dharma (calling) and enable their mutual līlā (divine play) to unfold independently. Sītā did not need a man to ‘rescue’ her. She was verily dēvī, the Divine Feminine Herself and by her own limitless power capable of protecting herself. She was the manifestation of Divine Śakti who could lift the mighty bow of Śiva effortlessly with her little finger. There are numerous points in the epic where she herself reveals her divinity. But how would Sītā’s extraordinary powers be of any relevance to the common women of the world? Would they be safe from the evil people who are waiting to violate them at the first opportunity? Sītā safeguarded her physical integrity with no weapon other than holding up a single blade of grass which Rāvaña would not dare to cross, failing which he would be burnt alive. But would that stop tongues from wagging in posterity? Would it not provide an opportunity to the world to besmirch Sītā’s character as of other women? Didn’t a certain washerman do so subsequently? Possibly they would say, Rāma gave in to desire and the māyā (weakness that leads to lapse of judgement) of a mere woman and therefore accepted Sītā back? That would put the veracity of both their avatārs under question. Sītā could destroy Rāvaña by her own tēja, the effulgence of her being alone. But that would not have been conducive to Rāma’s manly dharma as an ideal husband, to strive to deliver his wife from captivity of a powerful, unwanted male constraining her? Sītā is not a passive, helpless spectator of her fate, but allows herself to be delivered by her husband. She refused to be rescued by Hanumāna even though he had declared himself her son, because that is a husband’s manly dharma and due honourable action. She knew he would come to redeem her and he knew she would pass through the fire unscathed. They both made a statement of absolute, implicit trust. Sītā’s purpose was not to seek her own deliverance alone but that of the whole world by allowing the design of Śrī Rāma’s incarnation to be fulfilled of slaying the tyrant Rāvaña. The validity of their incarnation is in having lived as common people, among them, through the tribulations, sentiments and the feelings experienced by them and in that context demonstrating the ideal of the avatāra as maryādapuruśottama. The masterly epic is not premised on ideas of progress or regress of society.

“The salience of the kāvya, which is plotted along union and separation though, doesn’t hinge on notions or impressions of a society gone to seed. Both the ethos and mythos of the epic are misappropriated by such a fraught exigesis. It concerns male-female dynamics in a sensibility zone of excelling each other instead of a riven man-woman dichotomy.”

Śrī Rāma explains in the following ślokas quoted from the Vālmīki Rāmāyaña his object behind the enactment of this sequence:

एवमुक्तो महातेजा धृमानुरुविक्रमः |

उवाच त्रिदशश्रेष्ठं रामो धर्मभृतां वरः || ६-११८-१२

Hearing those words, the courageous Rāma of great prowess and the foremost of those upholding the virtue, replied to the fire-god, the best of gods.अवश्यं चापि लोकेषु सीता पावनमर्हति |

दीर्घकालोषिता हीयं रावणान्तःपुरे शुभा || ६-११८-१३

Sītā certainly deserves this pure factory ordeal in the eyes of the people in as much as this blessed woman had resided for a long time indeed in the gynaecium of Rāvaña.बालिशो बत कामात्म रामो दशरथात्मजः |

इति वक्ष्यति मां लोको जानकीमविशोध्य हि || ६-११८-१४

The world would chatter against me, saying that Rāma, the son of Daśaratha, was really foolish and that his mind was dominated by lust, if I accept Sītā without examining her with regard to her chastity.अनन्यहृदयां भक्तां मचत्तपरिवर्तिनीम् |

अहमप्यवगच्छामि मैथिलीं जनकात्मजाम् || ६-११८-१५

I also know that Sītā, the daughter of Janaka, who ever revolves in my mind, is undivided in her affection to me.इमामपि विशालाक्षीं रक्षितां स्वेन तेजसा |

रावणो नातिवर्तेत वेल मिव महोदधिः || ६-११८-१६

Rāvaña could not violate this wide-eyed woman, protected as she was by her own splendour, any more than an ocean would transgress its bounds.प्रत्ययार्थं तु लोकानां त्रयाणाम् सत्यसंश्रयः |

उपेक्षे चापि वैदेहीं प्रविशन्तीं हुताशनम् || ६-११८-१७

In order to convince the three worlds, I, whose refugee is truth, ignored Sītā while she was entering the fire.न च शक्तः सुदुष्टत्मा मनसापि हि मैथिलीम् |

प्रधर्षयितुमप्राप्यां दीप्तामग्निशिखामिव || ६-११८-१८

The evil-minded Rāvaña was not able to lay his violent hands, even in thought, on the unobtainable Sītā, who was blazing like a flaming tongue of fire.नेय मर्हति चैश्वर्यं रावणान्तःपुरे शुभा |

अनन्या हि मया सीता भास्करेण प्रभा यथा || ६-११८-१९

This auspicious woman could not give way to the sovereignty, existing in the gynaecium of Rāvaña, in as much as Sītā is not different from me, even as sunlight is not different from the sun.विशुद्धा त्रिषु लोकेषु मैथिली जनकात्मजा |

न विहातुं मया शक्या कीर्तिरात्मवता यथा || ६-११८-२०

Sītā, the daughter of Janaka, is completely pure in her character, in all the three worlds and can no longer be renounced by me, as a good name cannot be cast aside by a prudent man.

The part of Rāmāyaña that describes Sītā’s exile also needs a particular perspective to understand. This part of Rāmāyaña exemplifies the fulfilment of rājdharma, the ideal of a ruler who as prajā-vatsala-rājanya (a king committed to his subjects) puts the interests of his subjects above those of his personal goals. When the people of Ayōdhyā express the view that dharma was imperilled as a woman of questionable reputation, who had resided with another man was their queen, and they would as a repercussion have to tolerate the scandals of their own wives, Rāma is obliged to give in to their remonstrations, not because he doubted Sītā’s character, but to make them realise the consequences of the folly of humiliating a woman for her misfortune, as the washerman who criticised Śrī Rāma had done, and yet claimed moral superiority to the king by turning his dishonoured wife out of his house. To address the fate of this unfortunate woman and all such women in time to come was as much incumbent on Śrī Rāma, and not just safeguarding the place of his own wife. After Sītā was exiled, Śrī Rāma did not marry again and lived the bare existence of an ascetic to share in the fate of his wife as is the dharma of a husband. The injunction of the presiding hṛṣīs during aśvamēdha yagya conducted by Śrī Rāma reinforce the status of the lady of the house that there can be no worldly gain in the absence of the ardhāṇginī, the essential other of a man.

The epic beautifully reveals how as time passes the people of Ayōdhyā realise their mistake, having suffered the absence of their great queen and beg their king to bring Mother Jānakī back. The washerman tearfully repents his error in judging a wronged woman. But those who commit the sin of harshly treating the feminine bear the severity of the consequence of their sins. Sītā declined to return to Ayōdhyā. Sītā’s manner of exit from the world, the act of giving up the world and her body is a powerful statement: that if disregarded, Shrī (the feminine as prosperity, joy, light in our lives) can leave forever. Sītā represents feminine power and forebearance, the kind only women can possess. She can make or break a man.

The equation of a helpless, inferior, dependant wife owned by her husband, existed in Abrahamic religions, never in Hinduism. Rāma can never be worshipped without Sītā. They are equal, bound by mutual dharma, inseparable parts of each other’s incarnation. She is patīvratā just as Rāma is ēkapatnivrata. It is a contorted view of their characters that gives rise to such questioning.

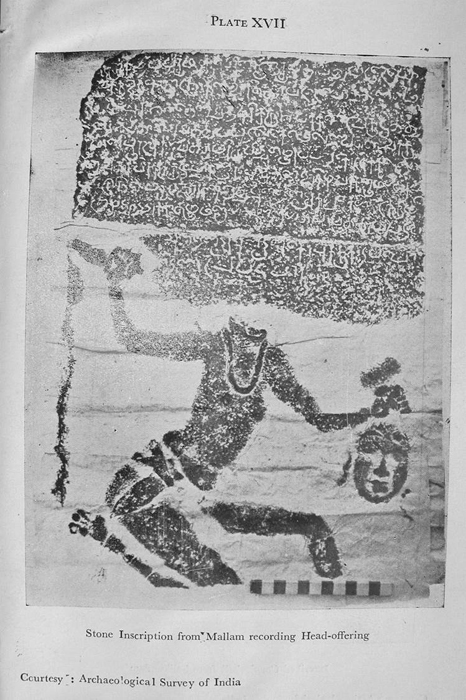

Going through a trial by fire, passing through water, emerging unscathed after being subjected to powerful elements of nature or otherwise going through great suffering to reveal the true nature of an illuminated soul is a recurring theme in edifying spiritual stories. It is acknowledged that the evolved mind rests assured in ‘knowing’ but weaker minds demand ‘proof’. Therefore examples abound of godly beings passing through an insurmountable ordeal in order to demonstrate faith. Why must the freedom of allegoric story-telling be acceptable in case of other religious literature while the Rāmāyaña is judged for the use of the same creative imagery? Whether it is the example of resurrection of Jesus rising from the dead after his crucification, or King Śivi cutting his own flesh and offering himself for the sake of dharma, Hṛṣī Dadhīchi sacrificing his life, Saint Kannappa Nayanar gouging out his own eyes for devotion to Śiva, or Dhyānu Bhagat severing his own head and offering it to the Mother Goddess Jwālā Dēvī, examples abound in stories of extreme sacrifice for a principle. There are examples even in history of heroes and saints who decapitated themselves for religious purposes and such was seen as noble behaviour. But selecting characters from a class of people perceived as ‘weaker’ by present-day sociological concepts (e.g., Eklavya – dalit, Sītā – woman) and their powerful, volitional acts for demonstration of individual principles for anachronistic portrayal as victims of oppression has definite motivations, targetting a demographic and defaming their dearly held values and destroying the traditions that comprise their culture.

The spirit of the Rāmāyaña is best conveyed in this quote:

“Great literature rises above the closed semantics of parable. It nuances the themes and forces you to keep pondering. Discursive overdetermination is not what sterling literature seeks to establish. The imponderables of life are examined, and truisms are put to test. Literature seeks to loosen up dogmas and hard-boiled notions about roles and set human responses while demonstrating the power and peril of the choices Man makes.”

First appeared as a Facebook post on October 15, 2016.

[Quoted lines are from Shri Ranjit Kumar Dash, Sr. Assistant Editor, Asian Age]

On the first place, one must understand there is a deep sense of meaning hid behind the act of Gods and their avataras. One must strive to seek answers to their doubts rather than accusing and cursing Gods for their actions. If anyone perceives Sita Ma had lost her purity they obviously lack the vision to see Ravana there. That said, it is the mentality of the men folks and society, in general, to conveniently shift the responsibility of the virtues of purity and chastity on women and turn a blind eye to men’s kaama icchai. If purity could mean shedding Moham (lust) towards unwanted desires including kaama icchai, in lowkeekam this must without be a virtue of both men and women. Accusing a woman of losing her chastity and purity for her illicit relationship and adultery without realising there is a male who is also a party to this relationship who has used his body to fulfil his bodily needs, is foolish and immatured. Society at large has decided Chastity is treasured possession of woman and squarely removes this from a man’s domain. Having a sexual relationship is a confluence of body and mind, in fact, it is the iccha of mind that drives to have a bodily relationship. When a man is involved in illicit relationship or adultery he has already proved he has given in for his kaama moha, which is the same for a woman. The union of Sharira (Body) as a result of iccha alone will have a differing impact on women i.e., pregnancy. Otherwise, it very well means both a man and a woman have allowed kaama to overcome their indriya nigraham. In this context forcing exclusivity of chastity on a woman and convincing that it is not a virtue to be preserved by a man is only misleading the society to a state of foolishness and thus leads to uninformed decisions like Agni Parksha which any normal mortal woman can not go through. Also, we only hear the term Pathivratha, but not anything called Pathnivratha (excluding Rama) in common life. Things like this, unfortunately, will lead to men thinking its fine for them to have casual sex outside or before marriage as they’ll think the woman will take the humiliation from society. In fact, it is advised by many many greats like Swami Vivekananda that a man has to not waste but preserve his semen to realise his true potential. Going by this, logically it is the man who needs to be accused of reducing himself to a low level and making a bad example out of himself to be only followed by other male youth. I only wish we judge men and women equally in this regard and not be partial to one half of the society.

Thank you for a thoughtful comment. Putting the onus of preservation of chastity on females alone had indeed led to the decadence of Hindu India and dilution of manly character. There is scare any talk of what manliness entails since all judgement and entire social commentary is focussed on demonstration of character by women. Well analysed!

Best regards,

Hritambhara