By Smita Mukerji

Read the previous section of this series here.

The Calcutta Quran Petition

When Chandmal Chopra filed a petition at the High Court of Calcutta in March 1985 seeking a ban on the Qur’ān on the grounds that its contents—according to the plea—instigate communal disharmony, powerful pressures were brought to bear in order to obstruct it by every possible means, by political players at the Centre as well as the State each vying to outdo the other in proving their secular credentials.

Muslim Lawyers in the Bar association moved a motion to condemn Justice Padma Khastgir for admitting the petition. The motion was however defeated since it did not garner enough votes.

The Union government decided to intervene directly sending the then law minister, Ashoke Sen, to Calcutta “for giving the necessary instructions.”[1] In his reply to MPs in the Lok Sabha, the Minister of State for Law, H. R. Bhardwaj stated that “when the writ petition had come to the Government’s notice, the Government had immediately considered measures to counter it” and that “the Government was deputing the Attorney-General to Calcutta to seek dismissal of the writ petition.” Dr. Balram Jakhar, the Speaker that time noted that, “there was enough trouble in the country and there was no need to add anything which would stir up another conflagration.” It is interesting to see that Dr Jakhar was more bothered about “trouble”—as though prompting Muslim mobs to take to the streets and create trouble—than the rights or wrongs of the case.

The West Bengal government similarly strained to distance itself from the petition with the Chief Minister at the time, Jyoti Basu, denouncing it as “a despicable act” and according to his own statement, asked the advocate general to speak to the Chief Justice of Calcutta High Court. Anil Mukherjee of the Forward Bloc represented in the Assembly that the petition should have been dismissed outright as “the subject matter pertains to religion.” The Government of West Bengal even attempted to harass the petitioners by turning over police records to fish out some pretext to use for a smear campaign against them.

The commotion carried on all the while the matter was sub judice and as such this manner of commentation and impedance constituted contempt of court, but the courts did not think it fit either to reprimand any of these overactive legislators.

“The accomplices of Islamic imperialism in India—Communists, Socialists, Nehruvian Secularists, Gandhians—were throwing all judicial proprieties and procedures to the winds in defence of Islam which they viewed as the most effective weapon against their common enemy—Hindu society and culture.”[2]

Interestingly, this flurry of unctuous disavowals failed to impress Pakistan, and that theocratic State with an abysmal record in treatment of its minorities, having all but decimated them systematically, made this petition an occasion to pontificate on religious freedom and rights of minorities, berating India for this “worst example of religious intolerance.”

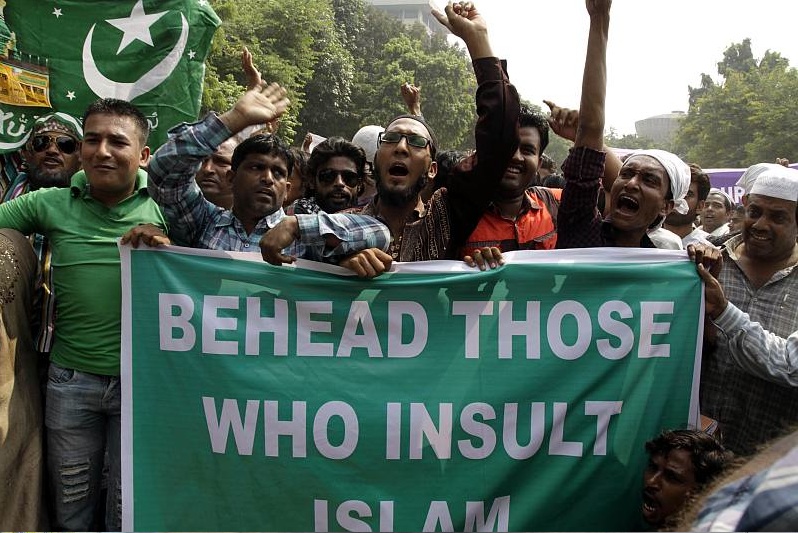

Almost as if on cue, violent mobs had been incited by Islamists all over the subcontinent in India, Bangladesh and Pakistan, with massive rioting, stone throwing, ransacking reported from various places. In the midst of all this, the Times of India published a series of three articles by Dr. Rafiq Zakaria in praise of the Qur’ān’s spiritual message, quite incongruously, considering the scenes of violent Islamic lumpenry unfolding right before the eyes, and thought by many in knowledgeable circles to be a command performance to mollify the Muslims. Apparently, the dread of mounting Muslim protests had paralysed all rational faculties in certain quarters.

The case was decided too with unseemly haste without a fair hearing, not even fair opportunity being afforded to Chopra. While he was still in the process of preparing the affidavit-in-reply as directed by Justice Khastgir, he was informed that he was to now appear before Justice Basak just the midnight before the hearing on May 13. On his appearance he was directed to move the writ petition afresh as a court application. His request for adjournment on grounds that he had received notice only for “to be mentioned” was rejected, and the Attorney-General of Government of India and the Advocate-General Government of West Bengal who had come well-prepared, were asked to proceed with their arguments against the petition. Ill-prepared, he tried his best to counter the arguments but his petition was dismissed and the judgement reserved for another day.

The judgement in the case delivered on May 17 was a class rendition of secular speciousness in all its empty pomposity. But what was worse was that it made an adverse comment on Justice Khastgir for allowing the petition. This was pounced upon by pugnacious Islamists to the accompaniment of carps on the permanent Muslim ‘grievances’ to further foment unrest demanding action against the Judge, that caused widespread rioting following the judgment, particularly intensely in Kashmir.

A Review Petition was filed by Chandmal Chopra subsequently on June 18, questioning the basis of the judgement as unsound citing eight grounds. But in violation of the judicial procedure, even this matter was put up before Justice Basak on June 21, and was summarily dismissed citing some trivial legal technicality without going into any of the grounds.

To be fair to Justice Basak, a layman opinion is insufficient to conclude that the judgement was incorrect under the existing law, by which it is perhaps impossible to impugn a book accorded the status of sacred scripture cherished by a certain community. “Law has its limitations, particularly in a country where its main corpus continues to be what alien regimes, Islamic and British, had devised for their own imperialist purposes.”[3] However the petition as well as the judgement must be inquired into from the point of view of its verity and logic. Our faculties of reason and moral sensibilities cannot be suspended on account of the belief of a section of people that a text revered by them is the divinely revealed word and their claim about its infallibility. That would be giving credence to collective superstition and insistent ignorance. But Basak’s judgement was pitched on precisely this premise.

Justice Basak took great pains, quoting copiously from various authorities and inserting his own literary and philosophical flourishes, to establish this fundamental assumption of the Muslims about the Qur’ān being of divine source. What the lengths of his elaborations ignored is that the writ petition did not gainsay this in the first place. On the contrary, it stated clearly that “the Quran, particularly in its Arabic original, moves Muslims to tears and ecstasy.” The central issue that the petition raised was not how Muslims hold the Qur’ān, but the behaviour pattern that is inculcated through its teachings in its adherents vis-à-vis the non-Muslims.

Based on this was Basak’s minor premise that if some ayāts sounded offensive, they would have been torn off from their proper context and interpreted in a manner that is not the import of the book.[4] He also included a broad-sweeping and wholly unsupported surmise that “This book is not prejudicial to maintenance of religious harmony,” and that “Because of the Quran no public tranquility has been disturbed upto now and there is no reason to apprehend any likelihood of such disturbance in future.”

One flaw that may straightaway be pointed out in the judgement is that the writ petition did not contain any “interpretation”, but the precise words contained in the text translated in English as they appear in a publication of an orthodox Islamic publishing house and by a translator regarded as competent by them. Neither are the cited passages selective or randomly culled in an attempt to portray the text in a baleful light. It presented instead an exhaustive list of what is held as Allah’s word on the manner to look upon non-believers and the treatment to mete out to them. The fact that these sayings are scattered over 30 chapters is owing to the peculiar manner in which the Qur’ān has been compiled, describing “revelations” supposedly received by the Prophet at different times and places, and in a variety of circumstances and subjects that follow neither chronological nor thematic order. The quoted passages do not alter or eclipse the “aim and object of the book”, rather highlight its central themes which is, apart from the prescribed handling of non-believers, how Muslims should form a militant brotherhood (ummāh) on the basis of uniform beliefs and behaviour.

The Qur’ānic passages do not embody abstract principles, but contain concrete rules of conduct and express injunctions on the course of action in various situations as exemplified in the life of the Prophet. In fact, allegorical interpretation (ta’wīl) is frowned upon by the ulema, the authoritative Islamic scholars, the qāzis, imāms and sufis alike, who stand for literal reading and matter-of-fact acceptance of the words of the Qur’ān.

The observation that the verses had been ‘quoted out of context’ hold no weight either failing a singular example of what was known as or thought to be the proper context by these legal luminaries for any specific verse quoted in the petition, from which the folly would be borne out. The statement is moreover inaccurate since context for the passages of the Qur’ān is not obscure, in fact is key to understanding its teachings, which however do not in any way elevate the meaning of its verses. The events surrounding and occasion for each one of the “revelations” received by the Prophet are meticulously recorded and can be narrated precisely by the meanest mullah in any nondescript village mosque. The language is neither ambiguous nor metaphoric, but precise and plain in every instance. Islam is not a mythical religion but a historical creed of short antiquity. There are six authentic (sahīh) collections of the Prophet’s traditions, or Hadis, commentaries on the Qur’ān that record a religious doctrine as an authoritative source of Islamic law, by connecting the Qur’ān’s verses with concrete events and situations in Muhammad’s life, drawn from the scores of available orthodox biographies that offer a wealth of first-hand historical material on him.

The authentic editions of the Qur’ān carry detailed information on the context of each sūrah (chapter) and ayāt (verse) in it, all of which is available in English translations done by pious Muslims as well as renowned Western Islamologists, which do not leave the meaning of any passage within the text in indeterminate space. The facile averments of the learned defence counsels which was echoed in Basak’s judgement, of lacking/unknown/incomplete/incorrect context, could have been rectified by providing the same by consulting any of these readily available sources, had they been really interested in doing so. In the absence of this, the judgement was no more than a repetition of the trite excuse employed by the defenders of the Qur’ān, a tendentious verdict not in the interest of justice, nor the truth, nor the well-being of our nation.

Cover picture source: TheConversation.com

[1] “The Union law minister, Mr Ashoke Sen, informed the Advocate-General that the Union Government would make itself a party to the case as it would affect the Muslim community all over the country and that he case would have international ramifications.”

[2] Sita Ram Goel

[3] Ibid.

[4] “Some passages containing interpretations of some chapters of the Koran quoted out of context cannot be allowed to dominate or influence the main aim and object of the book.”

First published July 1, 2018 at Jagrit Bharat.

Reblogged this on Saffron Storm Trooper.

Excellent article. I am yet to read Sita Ram Goel’s book. But it is already on my reading list.

Thank you so much. Do read upcoming parts in this series.