By Smita Mukerji

The Eastern State Penitentiary, Philadelphia

With a burgeoning population along with rapid economic development and conurbations that led to less cohesive communities, early 19th century America saw the emergence of large state-supported prisons, asylums and poorhouses in order to deal with the increasing number of criminals, lunatics and paupers, who could no longer be contained in neighbourly remedial set-ups and prisons, which came to be regarded as both inadequate and inhumane. With simultaneous reformative impulses arose the idea that defects of mind and character were correctible, which led to the establishment of institutions for confinement and reformation of deviants, especially in New York and Pennsylvania.

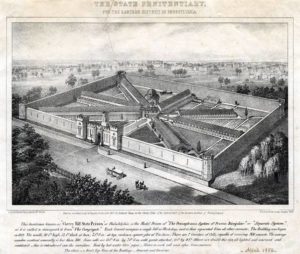

One of the landmark edifices of this era of prison reforms is the imposing Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) in Philadelphia which became operational in October 1829 and remained in use until 1971, after which it was closed. Designed by the British-born architect John Haviland, it was the first, biggest and most expensive incarceration centre ever built, which became widely known as the ‘Pennsylvania system of prison design’, along the lines of which a couple of hundreds of prisons were built subsequently all over the world[1], among them the Cellular Jail in Andaman.

The grim exteriors of ESP resembling a castle (though with faux battlements) were meant to intimidate though its goal was humanitarian: to serve as a ‘reformist asylum’ for those deemed incapable of self-discipline, founded in the belief that reform and rehabilitation was possible in a carefully controlled atmosphere. It was therefore called a ‘penitentiary’ instead of a prison, where it was envisaged that order would reign and those housed within might have a chance to be feel remorse for their crimes, and with this stated benign intention took cues from churches for the design of its interior halls.

Prisons in the 18th century were dismal places resembling holding pens where men and women, adults and children would be kept in cramped, squalid cells left to their conditions. Generally commercial ventures, they were filled with prostitutes and liquor, controlled by corrupt officials, with little to no order. Abuse by fellow inmates and guards was rampant and often starvation, cold, disease and violence put an end to prisoners’ lives before they were even sentenced.

In 1787, the ‘Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prison’ met at the house of Benjamin Franklin to discuss alternatives to this model, in the course of which the design for ESP was put forth. Benjamin Rush, a prominent doctor in the city[2], proposed building of a benevolent and salutary “house of repentance”, a large house with a number of apartments and one large room for public worship. The idea of solitary confinement cells was floated for the first time here to provide an atmosphere of contemplation to “those with a refractory temper” without being subjected to corporeal punishment. The proposed house would be supplied with means and materials for the inmates to carry out activities and work consistent with their skills. There would be gardens adjoining the house for the inmates to walk in occasionally for a beneficial effect not only upon health, but morals: “…for it will lead them to a familiarity with those pure and natural objects which are calculated to renew the connection of fallen man with his creator.”

(Source: Lily Landes/MentalFloss.com)

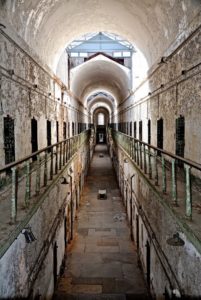

In Haviland’s design, seven single-level cell blocks radiated out from the central surveillance rotunda – from where one guard could see down all of the cellblocks just by turning around. The facility would have a capacity of 250 prisoners. But seven years before completion of the construction the first prisoner was lodged. By the time the third block was constructed the prison was already overcrowded and all subsequent blocks were constructed with two-levels, and could house 450 people when completed in 1836. But the numbers of inmates kept piling up and by the 1920s, 2 to 3 men were living in each cell. More blocks were added between the original buildings in 1870 and 1890. The last of these, ‘Cell Block 15’, was the death row, though no one served life in ESP, and prisoners sentenced to die were imprisoned elsewhere.

Sprawling over 11 acres of a cherry orchard and built (1822-36) at a cost of $780,000, ESP was in its day a technological marvel that afforded its inmates facilities which by the standards of prisons in those days made it a veritable paradise. Each of the vaulted cells was 10 feet in height and 8 x 12 feet in area, with curved pipes that heated the cells from a centrally controlled device, hot water and attached exercise yards. At a time when the US President Andrew Jackson still used a chamber pot, prisoners in ESP had their private toilets and a sink in each cell. The only source of light was a hatch at the ceiling which let in daylight in the manner of religious depictions of divine illumination shining down, aptly dubbed ‘the window of God’. The skylights were fashioned purposefully that way to lend the impression that God was watching over everyone. The inmates were served three square meals a day (usually consisting of boneless beef or pork, soup and unlimited potatoes). But despite all its material comforts, this “paradise” drove men mad.

The most prominent feature of ESP was a rigidly imposed daily routine, since the early superintendents believed this would encourage self-discipline. The reformers who conceived ESP considered isolation of prisoners to be therapeutic along the lines of the Christian belief that meditation in solitude on their behaviour and the ugliness of their crimes, free from the corrupting influence of other convicts would induce genuine contrition and reformation. A legislation was passed decreeing that “the principle of solitary confinement of the prisoners [must] be preserved and maintained” consistent with the thought that no good could come from inmates mingling in the prison or continuing those friendships in the real world.

French historian Alexis de Tocqueville and prison reformer Gustave de Beaumont, who visited ESP in 1831-32, summed up the expectations of the prison regimen in these words:

“Thrown into solitude [the prisoner] reflects. Placed alone, in view of his crime, he learns to hate it; and if his soul be not yet surfeited with crime, and thus have lost all taste for anything better, it is in solitude, where remorse will come to assail him… Can there be a combination more powerful for reformation than that of a prison which hands over the prisoner to all the trials of solitude, leads him through reflection to remorse, through religion to hope; makes him industrious by the burden of idleness… The habits or order to which the prisoner is subjected for several years … the obedience of every moment to inflexible rules, the regularity of a uniform life … are calculated to produce a deep impression upon the mind. Perhaps, leaving the prison he is not an honest man, but he has contracted honest habits.”

The completely sequestered unitary cells and different times of access to the exercise yards ensured that the inmates could not interact with the guards and other inmates and could not be recognised ensuring anonymity upon release. To keep them from communicating during trips outside their cells, they were forced to wear masks during the one-hour outing a day allowed to them preventing them from seeing any part of the prison except their own cells, so that they would not be able to map the prison mentally and escape. Eyeholes were allowed in hoods ca. 1890, but prisoners were still not allowed to communicate. Another reason for this was to avoid violence between criminals; as they could not see each-others’ faces. They ate alone, exercised alone and read the Bible (the only book allowed) alone. Guards even wore felt shoe covers so as to keep the prison as quiet as possible, to preserve utter silence, utter solitude, meant to inspire penance. But what it inspired instead was insanity.

The primitive psychotherapy of religion-based “moral treatment” failed to reform hardened criminals and doomed the penitentiaries to a custodial rather than a reformatory role. The naïve theories and poor execution saw the asylums rapidly degenerate into sinkholes of despair.

The archetypal reformation home drew many distinguished characters to study its procedures and conditions, but not all of them had a favourable view. Charles Dickens, who visited ESP in 1842, called the system “rigid, strict and hopeless solitary confinement”, and believed it “in its effects, to be cruel and wrong”. His words in the following note found in his journal, proved prophetic:

“In its intention I am well convinced that it is kind, humane, and meant for reformation; but I am persuaded that those who designed this system of prison discipline, and those benevolent gentlemen who carry it into execution, do not know what it is that they are doing.” He observed perceptively, “I hold this slow and daily tampering with the mysteries of the brain to be immeasurably worse than any torture of the body; and because its ghastly signs and tokens are not so palpable to the eye, … and it extorts few cries that human ears can hear; therefore I the more denounce it, as a secret punishment in which slumbering humanity is not roused up to stay.”

The looming, gloomy high stone walls of ESP are witness to its 142 year old history of suicide, madness, disease and torture. The personnel often lacked the training to help the inmates and coupled with overcrowding led to use of brutality for maintaining order. The guards and councillors inflicted physical and psychological pain through numerous means to enforce compliance. Though the round-the-clock solitary confinement was eventually abandoned in 1913, a far less pleasant solitary confinement –intended not for penitence but punitory– would be retained in the form of windowless subterranean cells called ‘klondike’. One of the most gruesome objects of torture practices was a ‘mad-chair’ to which recalcitrant inmates would be strapped with leather belts for days so tightly that the blood circulation of their joints often stopped and necessitated amputation of their arms or legs. Another was the ‘water bath’ in which inmates were dunked in ice cold water and then hung out on a wall in winter until ice formed on the skin. The ‘iron gag’ was another instrument of torture in which an inmate’s hands would be tied behind their back and strapped to an iron collar in the mouth, so that the slightest struggle against the bonds would cause the tongue to tear and bleed profusely. For the worst of them, there was ‘the hole’, a subterranean cell under Block 14 where they were left to suffocate and die with little food or fresh air, no source of light nor toilet, and no human contact for weeks.

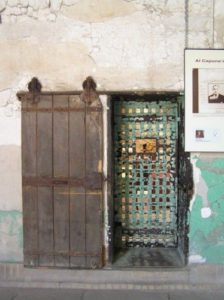

The Eastern State Penitentiary is a museum today. In the over 142 years of its functioning, the prison held over 75,000 criminals, both men and women, some of whom were famous. Al Capone, the famous Chicago gangster served eight months in ESP, as also the notorious swindler ‘Slick’ Willie Sutton, who was one of 12 convicts who escaped ESP through a tunnel on April 3, 1945. Several other tunnels were discovered in the course of renovation of the premises in the 1930s.

There is a spectral chill in the air in the now abandoned Eastern State Penitentiary compound which remained as a ‘preserved ruin’ for a couple of decades before funds were raised to restore portions of it, though much of ESP is at present in crumbling disrepair. Tales of paranormal activity abound and caretakers swear that the place is haunted and even for ‘unbelievers’ the heavy negative energy about the place cannot be missed. ‘Terror Behind the Walls’ is actually the name of a Halloween show held at ESP, which was turned subsequently into a museum site. Guided tours to the restored sections and several events are held all through the year.

Read the next section of this series here.

[1] Wandsworth Prison London, Old Bilibid Prison in Manila (Carcel y Presidio Correccional), Rangoon Central Jail, etc.

[2] An outspoken abolitionist who earned the title ‘father of American psychiatry’ for his groundbreaking observations about ‘diseases of the mind’.

Smita, Bravo! This was so well researched and narrated.

Thanks, Dagny! Appreciation from you means a lot!

Why was part 2 deleted..?

😔

The link to Part 2 is working now..Please check. Thank you. https://hritambhara.com/2019/01/08/terror-behind-the-walls-the-penal-colonies-part-ii/

Kudos on well researched article. Looks like the mindset behind incarnation methodology hasn’t progressed much in the civilized world.

Thank you so much! It does appear to be so.