By Smita Mukerji

“India without Hinduism is nothing.

A landmass, where invaders come and go.”

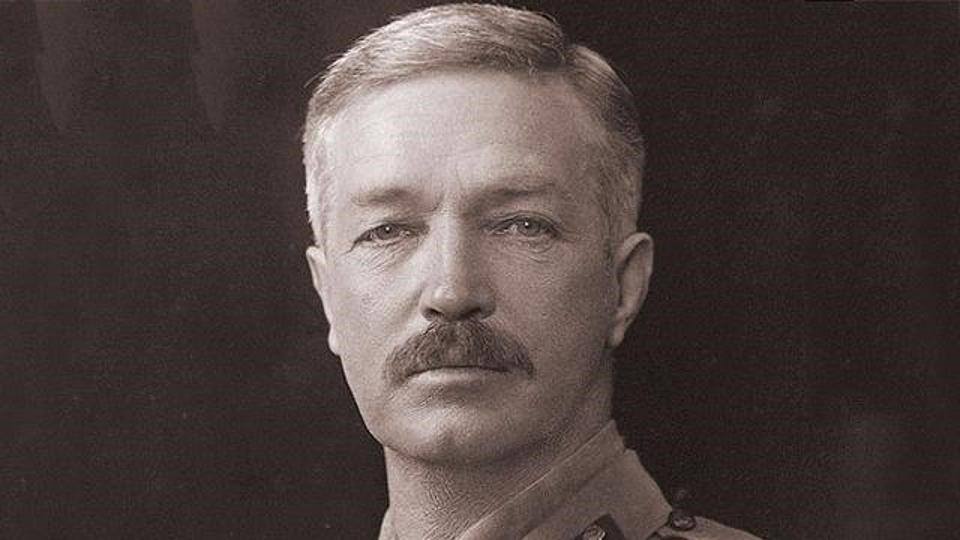

An excellent, thought-provoking article by author Rajat Mitra this Baisakhi again nudged my mind in a discomfort zone where one struggles to understand and assimilate an input. Baisakhi carries a painful memory for our nation, as the anniversary of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. This year marked the hundredth year since the bloody carnage of April 13, 1919 unleashed upon a gathering of innocent, unarmed Indians by a British officer, Colonel Reginald Dyer, who ordered an armed military unit of 90 men to fire indiscriminately into the crowd killing around 1,600 people and injuring 1,100 more[1], including children, the youngest being a baby six weeks old[2].

However, what is (rather, should be) more troubling to the conscience of Indians is not the act itself of an inhuman, mindless mass-murder committed upon them by a foreigner, but the fact that the act was carried out by Indians under his command, including those of common stock as the victims[3], who at the behest of an outsider fired mercilessly at their own hapless countrymen without qualms nor feeling any emotion at the piteous cries of the dying women, old and children from among their own people. The shooting is said to have continued unabated for around 10 minutes, and it stopped not because the soldiers were in any measure moved by the sight before their eyes, but because their supply of 1,650 rounds of ammunition was almost exhausted. It is indeed confounding that the men could have been desensitised to this extent and disconnected from their people!

Let us read Rajat Mitra’s view on this:

‘Jallianwala Bagh – Why Indians fired on Indians’

I lived in Hong Kong for some years. One of the facts I observed was that Hong Kongers by-and-large do not like Indians and many of them even hate us. Whether an Indian goes to look for a home or on the streets to buy groceries, the feeling is palpable. Many Indians I talked to said they feel it rather strongly. I had asked several people but got no satisfactory answer.

Finally, I asked a local friend about the reason. He was a historian at one of Hong Kong’s Universities. At first he tried to deny that this exists, but then later acknowledged saying the roots are historical. “Do you know,” he said, “the British came to Hong Kong in 1841 and when they tried to build the first police force with the help of locals, they realized that the loyalty of the locals could not be trusted to follow their orders or shoot and kill if their fellow brethren revolted or were in rebellion. But they realized they didn’t have the same experience in India. So they brought the Indians. The first batch of Indians who came brutalized and tortured the people here. The memory still lives in the mind of every person here and we haven’t forgiven you for it and will never do,” he said in a deeply emotional voice. “You Indians followed orders and didn’t show any mercy towards us which we expected you would do.”

I could only apologize to him and said it was an injustice. But what he had said left me perturbed. In social sciences ‘the other’ is a term that denotes how human beings divide, create walls with other groups whom they perceive as not similar to them and even inferior. For the American ‘the other’ is everyone who is outside America. For the British everyone who is not White and outside the country is ‘the other’. For the man from Pakistan it has become the Indian. Same can be said of the Chinese. But the curious thing for Indians is that for many an Indians ‘the other’ might not be an outsider but another Indian with whom his deepest chasm lies. He is someone whom we make into an enemy.

“You Indians, you have done it with your own people, like in Jallianwala Bagh. That is how the British controlled your nation for two centuries [sic], isn’t it?” These words of the historian have stayed with me since then.

In one of his books, Amitav Ghosh, the author, writes that the British believed that the Indians can always be relied upon to ruthlessly put down any one whether their own in India or anywhere else on their orders, something they could never imagine doing with anyone else. Would a Japanese be ever trusted to fire on his own people on the orders of a foreign General? Would a Chinese army have done so when asked? I believe the answer is a big ‘no’.

As one ex-General from the former British Indian army said, “The British were masters in making the Indian people believe that they were fighting on the side of the truth and so when the Indians fought a fellow Indian they saw him as evil and felt little or no guilt killing him.”

Is that why even today we are deeply divided, can torture a fellow Indian and feel little empathy, even shoot at him or beat him to death?

Why did we Indians create ‘the other’ amongst each other and not outside like other nations do? Once, a British historian at the mention of Jallianwala Bagh said, that a British police force or army would never shoot at its own people if asked to do so. Why could we Indians do it then? I believe it is worth finding an answer to this dilemma.

Why didn’t the police force refuse to follow Dyer’s orders and not shoot at their own people? This is maybe one of the most poignant and perplexing questions in understanding why British could rule India.

Has the notion of ‘the other’ as one we can hate and eliminate always existed amongst us in our history and as one that the British only perfected when they came in contact with us? I wish to ask this on the 100th anniversary of the tragedy of Jallianwala Bagh, whether we as a society created a gap within that can cause fissures and we can again be ordered into maniacal behaviour on the orders of a white man or woman.

Did we carry our philosophy of ‘vasudaiva kutumbakam’ too far and become like the subjects in Milgram’s experiment?

Jallianwala Bagh to me appears to be not the action of a deranged, crazy lunatic General but of a psychopath who knew this weakness of Indians only too well, who understood this mindset in us. He knew that when ordered to fire, the men wouldn’t stop because the cries of their own country men would have no effect on them. This philosophy, sick and dangerous, may need to be addressed and understood that could lead us to kill each other or destroy our unit. Will it ever lead us to become a united cohesive nation and not hold us back?

Creating ‘the other’ from among our own nation and making him into an enemy is dehumanizing which has just not only been symbolic, making us slaves, but also making us lose what is the most precious, our freedom. It deprived us of the power that rightfully belonged to us… as a nation.

Last year I visited Jallianwala Bagh. There were hundreds of people laughing, talking and taking pictures. Not a single face looked solemn. Only some seemed curious looking at the Well or the Bullet marks on the wall. Where does this detachment from our history come from?

Slavery dehumanized us Indians. As we know from history, no group cedes its privileges over others out of altruism but is forced to do so when the privileges they enjoy begin to threaten their survival. Gandhi could never do that to the British. Only once during the INA Trials and the Naval Revolt, it happened when the idea of one Indian being separate from ‘the other’ got erased terrifying the British into thinking it might bring their annihilation in India.

Will the present generation erase this blot? In it perhaps lies the security that will make our future generations safe from the contradictions that pushed our ancestors into slavery and annihilating each other.

The write-up assays an examination of Indians’ identity and affiliation, the cognitive elements that tie individuals to a nation. It would be illustrative to glance at another incident that followed the bloody massacre which is more disturbing than the act of those soldiers who fired into the ill-fated crowd that day: In the presence of a huge gathering of Sikhs along with the chief priests and leaders of the sect in the Golden Temple, the then jathedar of Akal Takht, ‘Giani’ Arur Singh, presented a siropa[4], turban and a kirpan[5] to the Lieutenant Governor of Punjab, Sir Michael Francis O’Dwyer, who had endorsed and condoned the action at Jallianwala Bagh. A description of the proceedings[6] on the occasion that record the exchange between the priest and O’Dwyer are revealing:

While the nation mourned the ghastly, unprecedented tragedy, the chief perpetrator was honoured at the holiest seat of Sikh tradition in a display of sickening, smarmy flattery. This was followed by a bulk offer of Sikh soldiers for the Afghan War by these community leaders. The psychology that produces such abasement in character that would descend to any depths of abject subservience to ingratiate oneself in the favours of another, ought to be investigated. It was this mentality that produced a steady supply of Indian soldiers ready to give up their lives in the service of the Raj as loyal slaves of their masters. It is this mental servility that makes Indians (many among them highly educated and with greatly developed mental faculties) grovel before ‘the white Gandhis’, symbols of the past foreign ruler, relinquishing all critical thought and compromising own dignity, and apparently with no part of their conscience discomfited at such self-degradation. The former Prime Minister of India, Dr. Manmohan Singh is a specimen case of this pathology.

In fact, Indians would probably be the only ones capable of stooping to such lows of obsequious sycophancy, extreme degree of loyalty and faithfulness to a foreign ruler, as long as their petty ego and immediate needs were being served. Whether serving their master in India or abroad, their conscience did/does not admit any consideration of principles or thought of right or wrong against a moral index, because such is defined by an awareness of what we are and what we stand for.

Indians lack an idea of self, especially one that identifies as part of a whole. Failing a greater identity the only interest Indians are attuned to serving are narrower, self-centric ones, devolving from region – community – clan – individual. The remotest conception of our illustrious origins in a glorious but lost civilisational past is absent (except in a half-baked way suited to corrupted present-day notional selves.) It is this absence of a sense of what we are that each one of their external interactions, both at the level of individuals and the nation, are laced with meekness, bereft of purpose and conviction in pursuing our overall interests, repeatedly surrendering our prerogatives to seek endorsement from those ‘other than us’. As a nation we lack self-assurance and look for validation from outsiders and make our judgment subordinate to the assessment of others. We would never have a person from one of the Western cultures, or say, a Japanese who, when holding forth their view would need to affirm it by quoting outsiders, ‘see, even Indians/Russians/Chinese think so’. But we see Indians frequently buttress their opinion with those of outsiders to give it more weight. They constantly crave such espousals and therefore the slightest pat of approval produces slavish fawning in them. They are keen to please rather than standing firm on their own well-founded sense of rectitude. Their estimation of themselves is beholden to external rather than internal parameters.

Did Indians always have this trait or did it become a part of our character somewhere down the ages? It is important to delve in this mentality because slavery was not the cause, but the consequence of this tendency that afflicts a significant section of Indians. This also has a bearing on the integrity of Indians. Indians seem to have always missed a clear idea of ‘who they owe it to’. They act as and when and according to what suits them. Their allegiances were/are often misplaced and entirely self-serving. There has been no dearth of quislings in our long history since ancient times, whose treachery caused immeasurable and irrevocable damage to our civilisation. The motivation of personal gain always overshadowed their sense about their collective, immediate or greater. And of the latter scarce anyone seemed to have ever been possessed. Much of our past has been documented as clan-histories glorifying local kings and heroes. What was clearly missing is a vision of India as a whole at any point. Is it really true then that Indian nationhood has been forged through colonialism and that it never had any real basis? If it did, why do so many Indians find it easy to dissociate with it for promoting self-goals?

If we look in our past, though the Indian landmass was fragmented into scores of kingdoms constantly in contention with each-other, Indians did have a clear identity of themselves as distinct from those outside their cultural complex referred to by them as mlećchas. This broad description applied to any foreigner, or those with a different set of saṇskāras (sensibilities or framework of values) and ritual ambience from the Indians and this essentially entailed preserving the distinction in communal associations and purity of practice. It was different from other more specific terms for foreigners recorded in ancient texts, like Śaka, Yona/Yavana[7], Huna, Kirāta, Rishika, Bahlika, Khāśa, Darada, Barbara, Pārasika, Pulinda, Tukhara, Kambojah, Pahlava, Turuśka, and several other groups of foreigners who were spread over and contended in Central Asia, and time and again made incursions into and settled around the northern and north-western parts of India, which led to interactions with the Indians. The term also implied those uncivilised, primitive or barbaric[8], an obvious statement of the cultural dominance of Indians which was contemporarily accepted by other groups of people who aspired to shed the status of mlećcha and be accepted into the superior cultural stream of Indians with passage of time. It was moreover a clear ethnic delineation since matrimonial contact with them was forbidden.

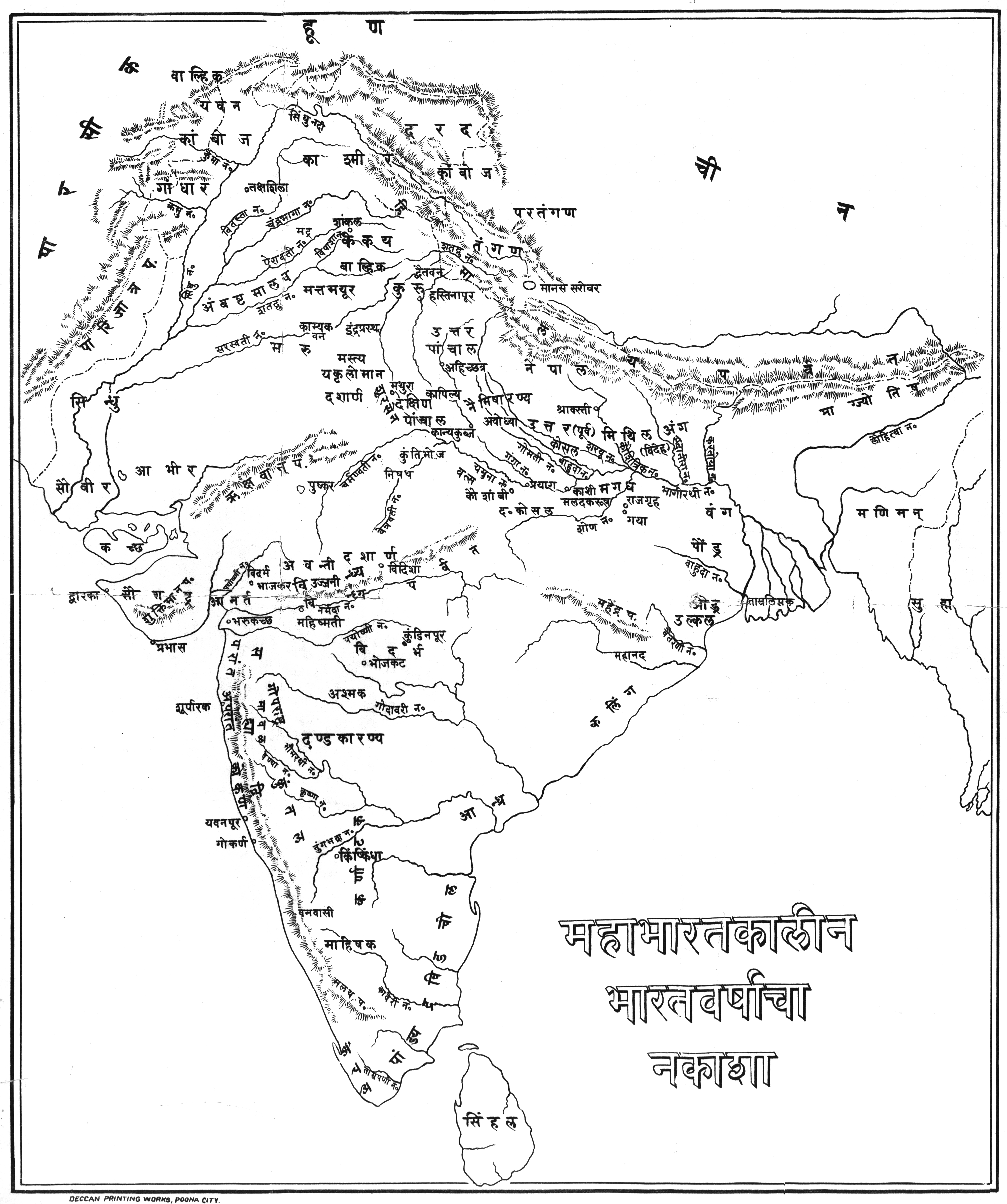

Indians since ancient times seem to have had a clear idea of the geographical stretch recognisable as the motherland of the Āryas[9] (as against the lands of various descriptions of mlećchas). One of the clearest references to Indian nationhood is found in the Viṣñu Purāña[10] that defines in very specific terms the constituents of Indianness. Chapters 3 and 4 of its second volume enumerate in detail India’s physical features, beliefs, practices, value system, social arrangement, also the tribes native to this land, and specifies the distinctive elements that set them apart from those outside the Indian cultural complex. The following verse describes the natural bounds of the landmass that forms the identity of its native people, referred to as ‘Bhāratī’:

उत्तरं यत्समुद्रस्य हिमाद्रेश्चैव दक्षिणम् ।

वर्षं तद् भारतं नाम भारती यत्र संततिः ॥ (2/3.1)[11]

uttaram yatsamudrasya himādeśćaiva dakśinam

varṣam tad bhāratam nāma bhārati yatra saṇtatih

The country that lies to the north of the ocean and south of the Himalayas is known as Bhārata, there dwell the descendants of Bharata (Bhāratī).

This clear cultural identity however did not seem enough to foster strong nationhood. Mlećchas were often part of armies of ‘Āryāvarta’[12] and were known to participate in wars with/against Indian kings. It was not unknown to have an Indian king ally with mlećchas to get the better of a rival.[13] This was not tellingly detrimental to India as Indian kings were still too mighty for the foreign tribes to overcome or challenge Indian cultural paramountcy which moreover was acknowledged as superior by the outsiders. This changed with the arrival of a new kind of tribe, the Islamic hordes. Will Durant, the American writer and historian writes of the Islamic invasions in India:

“The Islamic conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history. It is a discouraging tale, for its evident moral is that civilization is a precious good, whose delicate complex of order and freedom, culture and peace, can at any moment be overthrown by barbarians invading from without or multiplying within.”

At what point did the self-knowledge of Indians, of their perfected cultural ideation, of being the bearers of lofty civilisational inheritance start getting replaced with diffidence that degenerated into cringing submissiveness, cannot be said with certainty, but the wanton destruction of their magnificent edifices, the humiliation of their rulers, the degradation of their revered cultural symbols, witnessing the unprecedented scale and flagitiousness of slaughter by Islamic invaders over the centuries seem to have led to their successive diminution.[14] The Islamic hordes were fanatic barbarians who had no value for any of the advancements of kafirs and only cared for the religious merit by destroying any and all signs of their culture and beliefs.

The Indians completely failed to discern the difference between earlier hordes and the Islamic raiders pressing at the threshold of their ancient homeland, to foresee the destructive potential of the invaders fired by a new fanatic ideology[15] even when they saw it unleashed before them in its full bloody, unsparingly inhuman, genocidal magnitude, time after time. They continued with their old stratagems and wrangling to make the best out of the altered situation to gain advantage each for themselves, so blinded they were by narrow self-interest! They could not see the land slipping out of their hands, their civilisation rapidly being eroded, because they simply never had any broader overview of such.

The initial steep reverses notwithstanding, a protracted, doughty, resolute struggle by the Indians against Islamic invasions continued and with it persisted largely the awareness of being different from the barbarians. In this later period the term mlećcha and yavana came to signify almost exclusively the Muslims. But unfortunately the distinction did not serve to bring them together to recognise a common foe and act in unison. It was in fact not even good enough to ensure fidelity to their immediate group identity. In the siege of Chittodgarh in 1568, the Mughal victory was enabled largely by Rajputs and other Hindus[16] in the Mughal army. It is unfathomable how the Rajput nobles and soldiers in the Mughal army could have stood mute spectators to the ensuing horrific sack of Chittodgarh, symbol of the hoary Rajput legacy and pride, and the savage massacre by a foreign army of thirty thousand of their own tribe, with whom they had ties of common history and blood! Apparently it caused no pangs of conscience even thereafter, as the Rajputs who had allied themselves with the invaders continued their unwavering troth with the Mughals increasing their strength and numbers, which led to diminishing stature of Indian rulers and their conclusive elimination as political contenders in the subcontinent except in ignoble vassalage.

Perhaps the origins of servile demeanour among Hindus too can be traced to the culture of sycophancy in the Mughal court. In the preceding Sultanate era the battle was clearly drawn as one of survival in the realms dominated by Islamic rulers as there was no admittance for Hindus in the power centre. As the Timurid scion Babur rode into the political scene in India, a new paradigm arrived, as for the first time an Islamic ruler seated his Muslim bēgs and the Hindu rājās who fought for him together in his assembly as equals. Emperor Akbar was the first to include Hindus in power-sharing in an Islamic state formally inducted into the ranks of Mughal nobility. He however also instituted strict code of conduct to instil discipline that required complete cowering fealty to the Mughal crown and the slightest transgression invited extreme punishment[17]. Unquestioning servility was rewarded, the only way to gain in rank, and flattery was the order of court.[18] As Mughal rule grew in prestige and came to be widely acknowledged as the legitimate, ordained rulers of the people of India, this trait seems to have ingrained itself deeper in the Indian character. The earlier Indian monarchical system in contrast was not absolutist in the same manner, since a ruler was bound to act in consonance with long-established parameters of righteousness and therefore accorded ponderance to those learned in principles of governance consistent with natural justice and order. Though a dynastic autocracy, the traditional Indian state functioned more as an informal form of constitutional monarchy.

The greater portion of the Mughal army was comprised of mercenaries from several disparate Central Asian tribes, but there was another powerful aspect that bound them to the fortunes of the Mughal crown: Islam. Every Muslim knew that over and above the personal gain from the outcome of the wars they fought for the Mughal state, they fulfilled their ultimate religious calling of increasing the dominion of Islam. But what could have been the reason for the Hindus’ blind submission and self-effacing servitude to a foreign ruler? The thought of the primacy of Indians to rule over their ancestral domains did not cross their mind? They were ready to compromise on it, to make the land of their venerated forebears fair game for any prospecting adventurer? As rigid as most of these collaborators were in personal adherence to their cultural and religious practices, they saw no anomaly in facilitating the violation of their cultural and civilisational integrity to hold on to limited power handed out by an invader. The question is not whether this was the case, but why?

Was it the absence of the rigid boundaries of a nation-state that led to such deficiency in identity and association? But fact is, Indians are known to have acted (even presently do) against their national unit even when India was a clearly identifiable political entity with a distinct demographic and ethnic identity. Did Indians alone suffer from this lack of unity of purpose as a nation? In the 18th century many Europeans served as professional soldiers in the armies of Indian rulers. But one cannot think of a single instance of them having served so steadfastly as to betray their native land in a critical battle of survival.

It is something that goes beyond psychology to how Indians have evolved over their millennia long history. One very plausible reason for this feeble link with their overall unit would be the lack of structure in Indian belief systems. This meant that every Indian carried the onus of his own salvation, was free to determine the path and ultimately answerable to himself alone to justify the means since he bore the consequences ‘karma’ as well, in the world as well as hereafter. Each individual had a different reasoning according to their circumstance and level of consciousness and no one could be deemed wrong since there was no such absolute standard, and practically every position defendable from a unique personal perspective. This does not mean that there was no idea of what constituted treachery or the absence of crime and punishment within jurisdictions. It also does not mean that moral rectitude was not robustly discussed. In fact, if at all there is a society where every possible dimension and manifestation of human consciousness has been intellectually addressed and canvassed thoroughly, it is India. But unlike a unitary religious system no one’s conscience or choices were held accountable to a rigid set of moral and religious ideas that demanded compliance, conditioned minds to adherence and prescribed punishments at the failure to do so. It was a case of complete democracy within a monocracy.

This served the individual since it enabled optimal choice to chart one’s course according to their pace and unique nature, but it failed the unit since it set no definite terms of commitment for its preservation and in the end no one owed anything to anyone. In fact bigotry is foreign to Indian character. They are highly rational beings who rationalise everything according to themselves. Only that the rationale varies from each person to the other and is not dictated by any other set of considerations. While there might be great degree of coincidence there is no uniformity of principle. This is not the case with dogmatic religious systems where the sense of the individual is deferred to religious diktats. In the absence of a monolithic principle (e.g. prophethood, monotheism, shibboleths) to stand for, an ‘open-architecture’ belief system is inherently susceptible because it cannot defend itself.

A lacking central ideological mooring of Indians has been debilitating to Indian nationhood since there was at no point any convergence of viewpoints of all the parts constituting it, and the characteristic egocentric focus has prevented individuals from rising above it and kept them limited to the narrow interest groups suited to their immediate goals. But this very shortcoming of Indian belief system can be turned into the biggest cohesive force: by correctly articulating the overarching ideal and fostering an identity along those lines. This is what Vinayak Damodar Savarkar envisioned when he propounded the concept of ‘Hindutva’[19].

For this, one needs to flip the perceptional lens and take a look at ourselves from the perspective of the outsiders, the identity conversely assigned by outsiders to Indians. It is commonly known that the word ‘Hindu’ comes from Persian language, a term denoting the people of India, derived from ‘Sindhu’ (Persian for Indus – the river), and is an ethno-geographical reference, rather than religious. The Greeks called the land ‘Indica’. The corresponding Arabic word ‘Al-Hind’ referred to the land of Hindus. Though the term precedes Islam, it was used by Islamic writers and Muslims generally to describe those other than Muslims. The term ‘Hindu’ remained in use in the era of European colonialism as a negative appellation to differentiate adherents of Judeo Christian religions from those of Indian origin. Hindus are referred to in the writings of early European writers as gentiles (or ‘Gentoos’). The term included major distinct Indic spiritual streams, like ‘Buddhism’, ‘Jainism’ and ‘Sikhism’, since they shared the same philosophical concepts, such as dharma, karma, kāma, artha, mōkśa and saṇsāra, the rules of social association and saṇskāras (rites of passage). This common character of Indic religions in juxtaposition with Semitic counterparts, which not only contrast with them, but are antagonistic to them and even outright hostile to their existence, is one of the starkest determinants of national identity, which became the origin of the idea of ‘Hinduness’ or ‘Indianness’, termed by Savarkar as ‘Hindutva’.

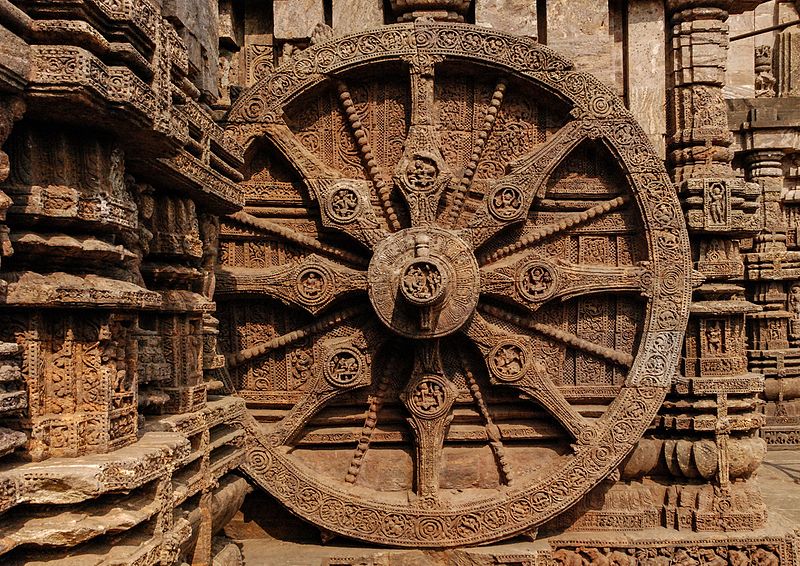

Considering the diversity of beliefs and practices of Indic traditions, it is important to school an outlook among Indians emphasising this concurrence in order to overcome their parochial attitudes. There is an immediacy of purpose to this collective identity, that of preserving their ecosystem which has been under attack from exclusivist, expansionist, predatory religious ideologies that seek to obliterate them. India is the natural motherland of adherents of the dhārmika group—as Indic traditions have now collectively come to be known—enactments in life of philosophies consistent with the eternal, natural order, and are based on universal principles of love, mutual respect, brotherhood of mankind and coexistence, also called the sanātana fold, meaning the eternal way. The vital common interest to safeguard this ecosystem that offers the scope of untrammelled growth of consciousness where individuals can exist at complete choice, is their strongest bonding factor. It is this organic milieu that permitted such mind-boggling diversity to flourish in the first place and an imperative to reinforce it, in order to resist the assault of inimical ideologies undoing their nation bit by bit. It is no surprise that the British writers with design sought to carve out separate identities of Indians, created faultlines pitting them against each other. Various pernicious forces continue to do so today and it is only the natural glue of ‘Hindutva’ which is the antidote to these, and therefore greatly reviled by them.

Superimposed concepts like secularism are antithetic to the continuance and survival of naturalist spiritual systems since these arose in the Western historical and sociological context that assume the paradigm of persecution of minorities at the hands of majority religious community, which simply does not apply to India. These moreover equate inclusive spiritual systems with dogmatic, supremacist religions like Islam and Christianity that lodged into the Indian body politic through force of violence, and with their intrinsic hostility towards native traditions continue to be practiced and propagated in a manner detrimental to the former, which effectively robs them of their defences and the right to constitutional protection. Holding Indian interests hostage to Abrahamic (born of prophetic traditions and their offshoots) frame of reference imperils India’s ancient way of life, as these are coerced, indoctrinating ideologies that interfere with and disrupt the dynamics of a freely-evolving society. Hindu ascendency is the only means of securing the freedoms of all religious communities, since it is inherently inclusive.

Savarkar stressed on cultural identity as the basis of nationhood. Addressing the land of birth as mother has been prevalent since ancient times[20] and became a spontaneous expression of Indian nationalism during the freedom movement.[21] This profound sentiment had the potential to integrate all classes and denominations of Indians into the Indian cultural mainstream, including Muslims and Christians, since conversion could not take away the fact of their Indianness and the land of their origin. Throughout the Islamic epoch Indian Muslims formed a distinct community and were identified in Islamic writings as such. The idea however ran aground against the concept of ummah (Islamic brotherhood) which denies ethnicity and race as basis of nationalism. Moreover, Abrahamic religious androcentrism roundly rejects the idea of divinity of the feminine that hinder reconciliation of converts on the basis of cultural sensibility. As easily as the mlećchas and yavanas of yore could be integrated into the Indian cultural mainstream, pan-Islamism and Judeo-Christian supremacism continued to sabotage the idea of cultural nationalism heftily, which cannot be regarded in any other way except utter perfidy of these communities in India. Another example of this ‘othering’ of the own people are leftist ideologues, who are so heavily indoctrinated into a preset framework of ideas that they lose all sense of self and connect with their unit, to the extent that they feel no compunction in actively working towards the annihilation of their own nation just to preserve their ideological context.

While Indians from the two major Abrahamic faiths continue to straddle conflicting identities, for the Hindus or the Indians in essence, cultivation and assertion of pan-national dhārmika unity remains the only chance of survival for our ancient civilisation. Instilling pride in what we stand for and clarity on the peril we are faced with if we fail to stand up, can alone stir us from our narrow focus and reinforce the national spirit.

May the New Year bring new light to all Indians!

Cover Picture:

Still from the movie Gandhi (1982) depicting the Scene of the massacre at Jallianwala Bagh on April 13, 1919 (Source: Wiki)

Quote: Ranjit Kumar Dash (Senior Assistant Editor, ‘Asian Age’)

[1] Estimates are varied

[2] Report of the ‘Disorders Inquiry Committee 1919-20’, better known as the ‘Hunter Commission’

[3] The group of 90 soldiers made up of Sikh, Gurkha, Baluchi and Rajput soldiers from the 2nd/9th Gurkha Rifles, the 54th Sikhs and the 59th Sindh Rifles.

[4] A traditional Sikh robe of honour

[5] A small dagger regarded as sacred weapon worn by Sikhs

[6] S. R. Bakshi, ‘Nationalism and British Raj’, quoted from ‘The Life of General Dyer’ by Ian Duncan Colvin

[7] As used to refer specifically to Greeks

[8] Not all foreigners though were regarded as uncivilised, e.g. the Pārasikas (Persians) were considered civilised, and still others, e.g. the Greek tribes (Śakas, Yonas, Kambojahs, Pahlavas, etc.) were described as ‘fallen kśatriyas’.

[9] Those of chivalourous, noble characteristics, contradistinction of ‘anārya’ (unrefined, ungracious, uncultured)

[10] Existed in written form at least by first millennium B.C.E., likely to have been orally transmitted from much earlier times.

[11] ऋषभो मरुदेव्याश्च ऋषभात भरतो भवेत् ।

भरताद भारतं वर्षं, भरतात सुमतिस्त्वभूत् ॥ (2/1.31)

ततश्च भारतं वर्षमेतल्लोकेषुगीयते ।

भरताय यत: पित्रा दत्तं प्रतिष्ठिता वनम ॥ (2/1.32)

hṛṣabhō marudēvyāśća hṛṣabhāta bharatō bhavēt ।

bharatāda bhārataṁ varṣaṁ, bharatāta sumatistvabhūt ॥31॥

tataśća bhārataṁ varṣamētallokeṣugīyate ।

baratāya yataḥ pitrā dattaṁ pratiṣthitā vanam ॥32॥

Hṛṣabhanātha was born to Marudēvī, Bharata was born to Hṛiṣabha, Bharatavarṣa (India) arose from Bharata, and Sumati arose from Bharata. (31)

This country is known as Bhāratavarṣa since the times the father entrusted the kingdom to the son Bharata and he himself went to the forest for ascetic practices. (32)

[12] Loosely, ‘land of the Āryās’, though the ancient term ‘Bhāratavarṣa’ denoted a much greater expanse

[13] There is mention of mlećchas as military allies of sage Vaśiṣtha against sage Viśwāmitra; the Mahābhārata mentions mlećcha tribes as part of the Kaurava army against the Pāṇdavas, and Prince Āmbhi of Takśaśilā had famously some nature of alliance with the invading Macedonians under Alexander. The famous 4th century B.C.E. Sanskrit work ‘Mudrārākśasa’ mentions mlećcha tribes as part of Chandragupta Maurya’s army as well as an alliance against him involving mlećcha chiefs.

[14] Abu Nasr Muhammad ibn Muhammad al Jabbaru-l ‘Utbi describes in ‘Tarikh-i-Yamini’ how after the successful siege by Mahmud Gazni in Waihind in 1002, Jaipal, the Shahiya kind of Kabul, the royal family and members of nobility were paraded bound in ropes before their subjects to morally shatter them. The king and the ladies of the royal family were lined up, publicly displayed at slave auctions along with their menials to humiliate them and break their collective will.

[15] It is amazing that in the millennium since the beginning of Islamic invasions, though there were several Islamic scholars who undertook the study of Indian knowledge, philosophy, sciences, practices and beliefs, not a single Indian king ever undertook or commissioned a study of Islam and its fundamentals, its ideological basis and consequently they just could not read it as they dealt with it, struggled against it, negotiated with it or interacted with Muslims. There was a complete absence of any critical study of Islam and its dynamics, the psyche of Muslims and that of the converts, the ever-swelling numbers of sworn enemies of their civilisation, faithful agents and perpetrators of the same violence, treachery and bigotry through which they were converted, as the members of a mafia. It has been the single most debilitating failure of Hindus and the reason they failed to regain control over the fate and course of their country. It is inconceivable that as a people Hindus could be and still refuse to look at what drives Islam.

[16] It was notably on Todar Mal’s suggestion that sabats (a contrivance peculiar to Indian warfare for overtaking strong forts heavily reinforced with battle apparatus) were built that eventually led to the fall of Chittodgarh.

[17] Barely into the fifth year of his reign, Akbar had one of his Mongol nobles arrested for the error of saluting him from horseback.

[18] This was very unlike the association of Indian kings with their nobles based on mutual respect and honesty.

[19] The term was first coined by Bengali essayist Chandranath Basu (1844-1910) in a tract titled ‘হিন্দুত্ব বা হিন্দুর প্রাকৃত ইতিহাস’ (1892) – ‘“Hindutva” or the True History of the Hindus’, an exposition on the quintessence that forms the consciousness of being Hindu, or ‘Hinduness’, putting together the highest and fundamental articles of faith of Hindus irrespective of divergences in the form of various schools. It was the first ever conceptualisation of an all-encompassing identity of the Hindu nation. The philosophy and form of the Hindu nation had been elaborated on by other thinkers like Nabagopal Mitr (1840-1894) and later, Benoy Kumar Sarkar (1887-1949) in ‘হিন্দু রাষ্ট্রের গড়ন’.

[20] The Vālmīki Rāmāyaña contains the following words in a verse as uttered by Śri Rāma: ‘जननी जन्मभूमिश्च स्वर्गादपि गरीयसी’ (jananī janmabhūmiśća svargādapi garīyasi – The mother and motherland are superior to heaven).

[21] The phrase ‘vande mātaram’ (salutations to the mother) from Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay’s ‘Anand Math’ became the slogan of every Indian as a powerful articulation of devotion of patriotic Indians towards their motherland and simultaneous protest against foreign occupation.