By Smita Mukerji

Read the previous section of this series here.

“When army commingled with army

They stirred up the resurrection-day upon earth.

Two oceans of blood shocked together:

The soil became tulip-coloured from the burning waves.”[1]

T H E B A T T L E

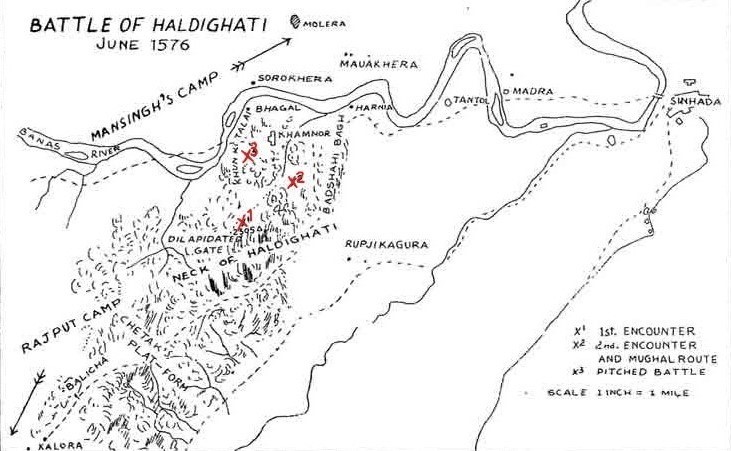

Haldighati was not entirely unfrequented, as it lay on the way to Gujarat, trod by pilgrims on their way to Mecca. The Mughal generalissimo Man Singh however showed a patent dread of venturing close to it and dithered in Molela (Molera) pitching tents, collecting provisions and inspecting his surroundings, hovering around the approach to the defile, whose narrow sinuous tracks occasionally opened into wider spaces sufficiently capacious to encamp a whole army.

The Battle Array

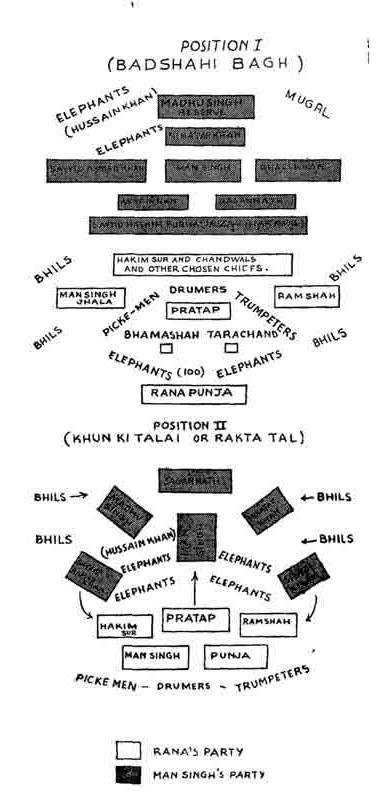

By most reliable accounts, the Rana’s army consisted of 3000 cavalry[2], 2000[3] infantry, and 100 elephants, accompanied by a 100 pick-men, drummers and trumpeters. According to Mughal sources,[4] the Rana was not in favour of marshalling his forces, but did so on the advice of his chiefs. The Akbarnama relates that their divisions corresponded to traditional arrangement of the Rajputs, ordered into harāwal (vanguard), chandāwal (rearguard), vāmpārshwa (left flank), and dakshinpārshwa (right flank), altered to the local conditions of Haldighati. The 800-strong van was led by Hakim Sur Pathan, a descendent of Sher Shah Suri, who had pressed to the Rana’s standard against the Mughals. He was supported by Chundawat Kishan Das of Salumber, Dodiya Bhim Singh of Sardargarh, Rawat Sanga of Deogarh and Rathore Ram Das of Badnor (son of Jaimal of the Chittodgarh siege fame). The 500 strong right flank was led by Raja Ram Sah of Gwalior, along with his three sons, Shalivahan, Bhanu Sinha and Pratap Sinh Tanwar, while the left flank consisting of 400 men was put under Man Singh Jhala’s command, supported by Jhala Man Bida of Badi-Sadri, Man Singh Sonigara (son of Akhai Raja) of Jhalor.[5] The rear was held by Rana Punja of Panarwa, followed by Purohit Gopinath, Jagannath, Mehta Ratan Chand, Mahasani Jagannath, Keshao and Jaisa, and charans of Soniyana. The centre was occupied by the Rana himself at the head of 1300 horsemen, supported by his Minister Bhama Shah, and the brother of the latter, Tarachand. The 400 odd Bhils who had accepted the commission of ‘Rana’ Punja were posted atop the numerous hillocks of the ghāti armed with their traditional short swords, bows and arrows and rocks to be hurled at the enemy.[6]

Then, on June 18[7], 1576 Man Singh moved his men (around 5000 regulars as per Badayuni[8] and 4000 of his own Kachwaha clan, and another 1000 other Hindu auxiliaries) to a clearing just below the dale and organised his battle array. A chosen party of 80-85 skirmishers who would bear the brunt of the first assault, led by Sayyed Hashim Berha formed the frontline, called Jauza-i-Harawal. Behind this was the advance party (iltmish) made up primarily of Kachhwaha clansmen led by Raja Jagannath (Man Singh’s uncle) and was supported by Asaf Khan and Khwaja Ghyas-ud-Din. The strongest point in their line was the right wing, composed of the Sayyeds of Barha, under the command of Sayyed Ahmad Khan, a position considered most dangerous and honoured, reserved for those known for their hereditary valour. The left flank put under the command of Qazi Khan Badakhshi (later called Ghazi Khan) and buttressed by Rai Lonkarn Kachhwaha of Sambhar, was positioned at the mouth of the pass (dahna-i-ghati) south-east of Khamnor. From here the Mughal battle line stretched westwards up to the Banas river. A reserve company was put under Madho Singh while the rear was brought up by Mehtar Khan (commander of Ranthambore). Man Singh took up position in the centre on an elephant while the chronicler Badayuni was with some special troops in the advance guard. Leaving aside the Hindus and the Indian Muslims of Barha and Fatehpur, the imperial troops were all crack cavalry and archers from Central Asia (Uzbeks, Kazhaks and Badakshis). The Mughals could not deploy any artillery or heavy ordinance given the impossibility of transporting it over the terrain, but used musket fire. The Rajputs did not employ any firearms.

Description of the Battle

It was however not possible for the Mewari army to hold their position since, after both armies had waited considerable time for the other to assume the offensive, the Rana ultimately decided to give battle and the Rajputs issued out to charge.

Early in the morning of June 21, 1576[9] the elephant bearing Mewar’s standard appeared from the opening of the dell and behind it debouched from the West side of the hill (q’blaruia-i-koh) the Rana’s van under Hakim Sur Pathan, and sweeping aside the Mughal skirmishers in a trice, rolled them on the imperial van, upon which fell the raging torrent of Afghans with such ferocity, that they spilt almost instantaneously and “were about to sustain a complete defeat”.[10] The scene of this first clash of arms was to the north-west of the ghāti. (X1 in picture), according to Badayuni, an uneven ground full of brambles and serpentine windings.

Following the van the Rajput centre burst forth from the waist of the pass (az’mian-i-ghati) led by the Rana himself[11] and descended upon the enemy like doom. Unable to withstand the onslaught the Mughal ranks broke formation and bolted. Jagannath was stranded fighting for his life in desperation and could be rescued only with great effort by reserves sent in by Madho Singh, and the Mughal van retreated to the security of their centre.

Next, the Rana’s right wing under Ram Sah sallied out and launched a savage attack on the Mughal left flank and put them to flight. The Sheikhzadas of Sikri (kinsmen of Sheikh Salim Chishti) and Lonkarn’s corps who were holding the left line fled “like a flock of sheep”[12], as also the grievously injured Shah Mansur, and passing by the Mughal van took refuge in the right wing. The Rana charged at Ghazi Khan who tried to hold out but receiving an injury soon hightailed it seeing the wisdom of the words “Flight from overwhelming odds is one of the traditions of the Prophet”[13], and the Mughal left was all but vanquished.

The Mughal right flank tried in vain to check the progress of the Mewar army but were rocked back on their heels by the impetuous assault. The Mughal frontline, advance guard and the left and right wings were completely scattered. Most of the soldiers took to their heels to escape with dear lives. Some riders did not draw reign until as far as 15-20 kms from the scene.[14]

Taking advantage of the crumbled Mughal lines, the Mewari right now penetrated the Mughal centre and pushed ahead[15] as Man Singh frantically tried to rally his men, who were however unable to contain the Mewaris’ advance. A fierce hand to hand combat now raged between the armies at the centre (X2 in picture), where the Rana chose to concentrate his energies.[16] After biding out of action for almost a decade, the weapons of the sanguinary Mewaris came in free play strewing the field with blood and carcasses of the enemy.

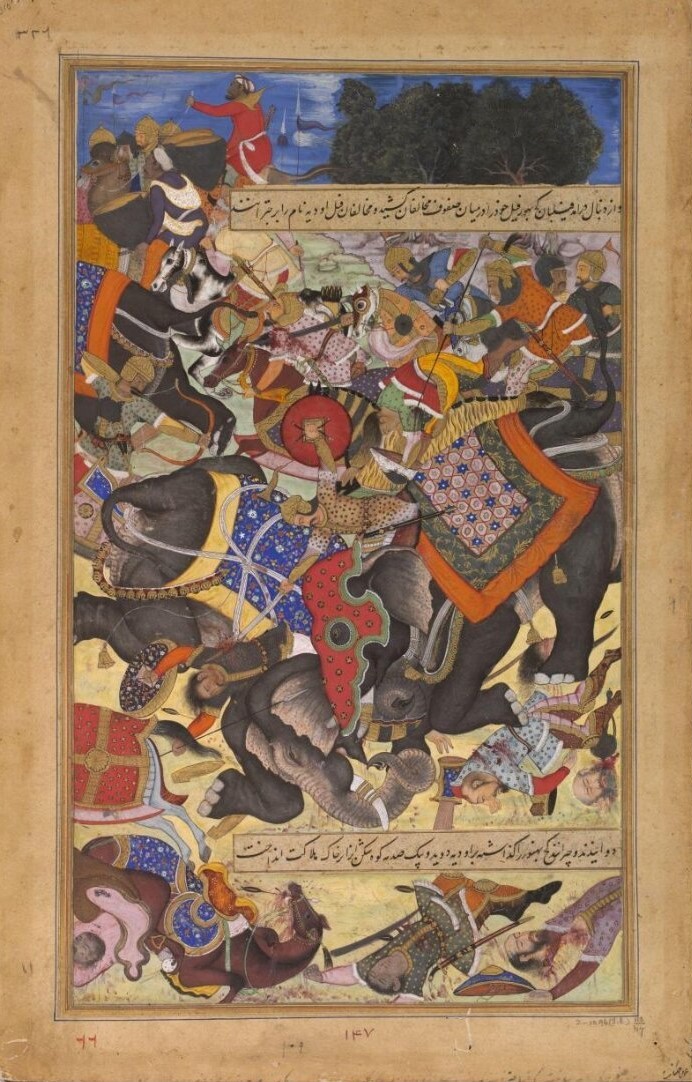

At this point, the Rana decided to send in his elephants to further terrorise the enemy. He was anxious to wrap up the battle swiftly by getting the better of the freaked Mughal ranks before they could gather themselves since, being vastly outnumbered, he had no recourse but to mount a full frontal assault forced committing all his men, and did not have any reserves.[17] The Maharana’s prized elephants Luna and Ramprashad caused mayhem in the Mughal centre as the Rajputs pushed further ahead, now dangerously close to the Mughal general, Man Singh. The Mughals too pressed their elephant Gajamukta to clash with Luna, but he got injured and had to retreat. Luna too had to be withdrawn since his mahout sustained a fatal shot. The imperial elephants Gajraj and Ran-Madar were plied to meet Ramprashad. The coveted elephant was ultimately captured by the Mughal faujdar Hussain Khan when his mahout was killed.

Just then, emerging out of the dust and scrimmage, Man Singh noticed a looming spectre appear before him, and suddenly the towering figure of the Rana astride his trusty steed, Chetak, was upon him. Before Man Singh could recover, the Rana, smiting left and right through the surrounding guard, had propelled himself within striking distance of him.[18] Spurring his majestic charger, dressed with a head-gear to give him the appearance of an elephant, to plant its forefeet on Man Singh’s elephant enabling him to deliver his blow tellingly, the Rana hurled his spear at the Mughal general. Man Singh dove into his howdah just in time to parry the blow and wheeled his mount around to make a getaway.[19] The spear struck the steel of the howdah and Man Singh was saved, though his mahout fell down dead.

Jadunath Sarkar has discounted the description of this encounter[20], however it is recorded in Mughal as well as Rajput sources, though in varying manner.[21] But the emotion ascribed to the Rana’s move, that he was seeking an engagement with Man Singh to settle a score, seems fanciful. The targetted movement of the Rajput divisions towards the Mughal centre indicate, that given the huge disparity in numbers to his disadvantage, the Rana’s strategy had been to quickly destroy the leading ranks to secure the gains made in the initial charge and gain an upper hand in the battle. Finding Man Singh within range he had taken his chances to injure or possibly kill the Mughal commandant to force the enemy to abandon the ground and concede the battle.

But having ploughed into the heart of the affray the Rana was in no small danger now. His steed was injured, a spear at the trunk of Man Singh’s elephant having pierced one of its feet. Seeing their leader in trouble the Rajputs in the imperial ranks fought with desperate urgency. The active operation by the Rana had drawn the attention of the enemy soldiers on him and he found himself surrounded. A hail of arrows directed at him by Madho Singh’s men inflicted several wounds on the Rana, who counter-attacked veering all around and killed Bahlol Khan with a single mortal stroke of his sword, slicing him vertically into two along with his horse. Plying his sword and spear he cut his way through the rush of Mughal soldiers back to his lines where Jhala Man Bida, who had swerved from his original position in the right, hastened to his side. He had been rendered free to assist the Mewari centre having beaten the Mughal left wing to a skedaddle.

During this stage of the battle, which had shifted now to a plain to the south-west of Khamnor that extended upto the southern part of the River Banas, the Muslim cavalry hung about at the periphery of the storm shooting their arrows and bullets with unerring effect into the mingled mass of Rajputs contending in the middle, mostly indiscriminately. Badayuni ventured to ask Ali Asaf Khan how they distinguished between the imperial Rajputs and the Rana’s troopers, to which he replied sardonically that it did not matter: “whichever side a man falls, it is a gain for Islam because it is one Hindu the less.”[22], [23]

All this while, Mehtar Khan, detailed to the reserve, had watched stupefied the Mughal commanders and rank and file turn tail and dart off in all directions to save their lives, the way they had not done in the two decades since Tardi Beg’s craven defeat at Tughlaqabad. The completely anticlimactic rout and the incongruous scene of Mughal soldiers running pell-mell left him bemused. He suddenly came to from his daze and decided to join the battle instead of standing around in the sidelines. To make the scurrying Mughal soldiers fall back in line he started beating the kettle drums and shouting the report that the Emperor had arrived in person.[24] The device succeeded in getting the spooked ranks get a grip over themselves and stop their flight, and rallied them to turn around and once more engage with the Rajputs.

The rally turned the tide of the battle irretrievably, as with the arrival of reserves the Mughals were able to make a better stand. Superior numbers soon started to tell upon the fortunes of the day. By this time the momentum of the initial onset was spent and five hours of continuous fighting in the extreme mid-June heat had sapped the Mewaris. One by one their leaders were felled fighting heavy odds. Ram Das Rathore met the heroic death of his father, as did Ram Sah of Gwalior along with his three sons, paid back richly the kindness of Mewar’s sovereign in incurring the imperial wrath by harbouring them.

The Rana’s own life was threatened now as Mughal ranks closed in, an easy target, made conspicuous by his insignia. His lines had crumpled up and crowded in the centre, hemmed around from three sides by enemy soldiers pouring in from all directions, with each passing moment making the chances of getting away all the more bleak. And then in the closing moments of the battle, an act of purest Rajput devotion was witnessed.

The Rana was too chivalrous to leave the field, but it was useless for the hope of Mewar to lose his life in that battle. Realising the crisis, in a moment’s decision Jhala Man Bida snatched the Rana’s standard and rushed forward shouting that he was the Rana, defying the imperialists to face him. The ruse succeeded and the Mughal captains, each eager to win the honour of being the captor of the Rana, converged upon him, and thus drawing the full force of the enemy attack on himself he released the pressure on Pratap. His faithful chiefs seized the bridle of his courser and turned him towards the pass in the rear who then “marched around and carried his master away from the peril.”[25] Jhala Man Bida met the death he had courted and with his fall the rest of the Mewar army dissolved and deserted the field or were killed in retreat.[26] The remaining chiefs, Rathore Shankar Das and Rawat Netsi offered resistance for some time but soon perished. Immortalised with this battle were also the chiefs Sonigara Man, Dodiya Bhim, Hakim Khan Sur, Rama Sandu and 350 Rajputs, their lifeblood consecrated to the Thermopylae of Rajasthan.

In the next section we rejoin the Rana in his further course and analyse the nature of this conflict and its outcome.

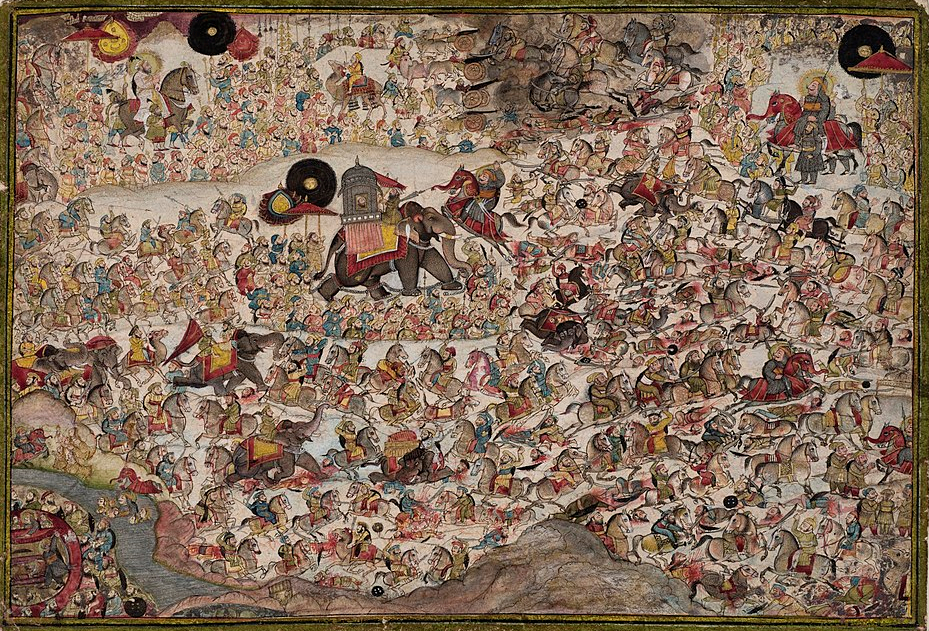

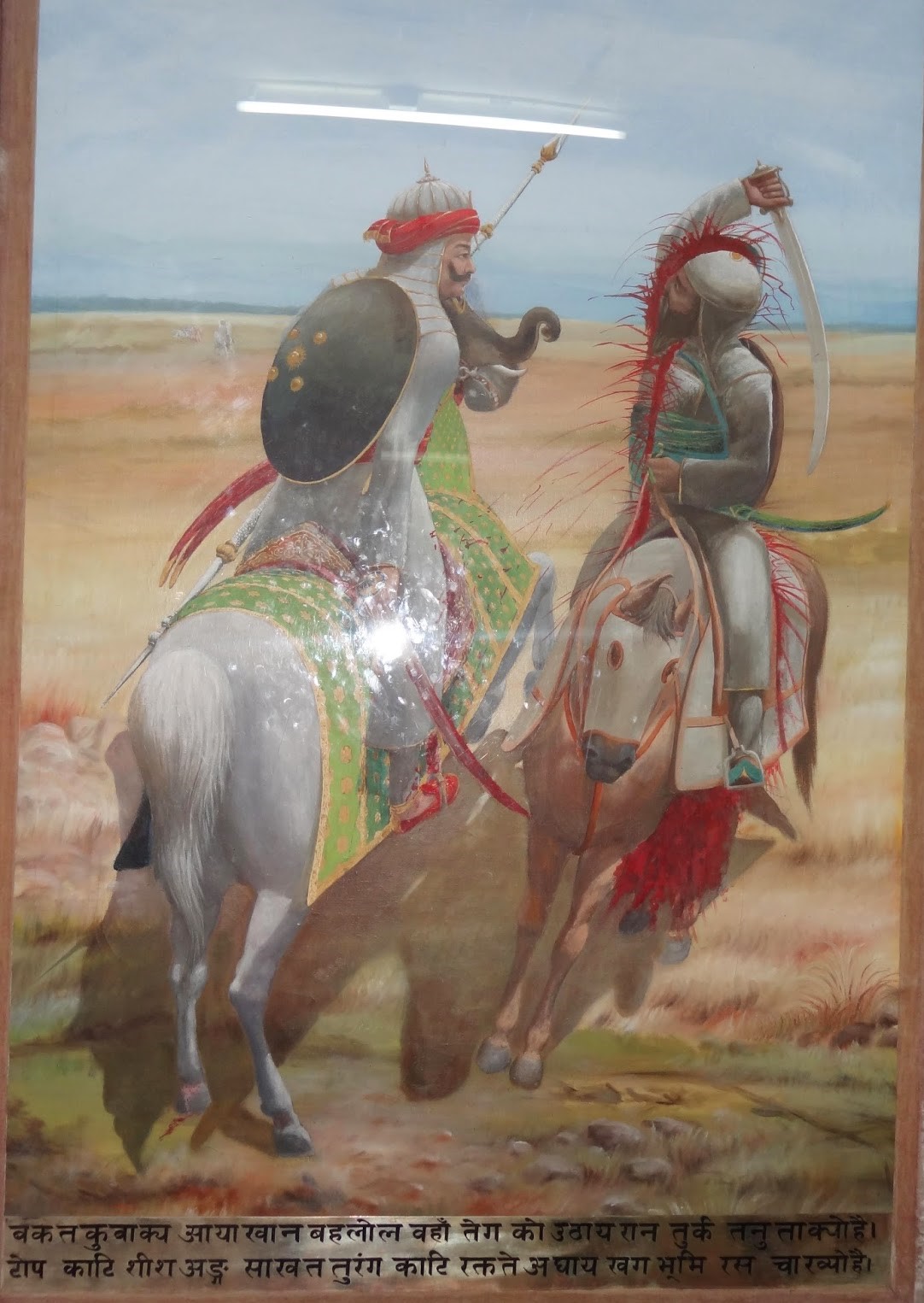

Cover Picture:

18th century painting depicting the battle of Haldighati, by Rajasthani painter, Chokha (Source: Wiki)

Read the next section of this series here.

[1] Abu’l Fazl (Akbarnama)

[2] Badayuni (Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh, Vol. II)

[3] Suryavansh, Folio 54(a) (Most sources however do not mention foot-soldiers in the Rana’s army.)

[4] Iqbalnama and Akbarnama (Chapt. XXXII, pg. 245)

[5] The Gallant Rao Chandrasen’s participation in this battle does not find mention though he is mentioned to have sought shelter in Mewar around that time.

[6] It however never came to their participating in the action since the battle scene shifted to the open area, as we shall see.

[7] June 21, by some accounts

[8] “And 5,000 regular troopers, partly from his own body-guard, and partly belonging to the Amīrs who were in command, he [the Emperor] appointed and dispatched as his force.”

[9] MuT-II, Akbarnama – Vol. III, Jagannath Rai inscription (Verse 41), Epig-Indica – Vol. XXIV, ‘Raj Ratnakar’ – Canto 7, V. 17 (“प्रातः पुनः ध्वनति चाह चातुर्य घोषे”)

[10] Badayuni (MuT II, p. 236)

[11] “The Rana came into the field from behind the defile (az’aqb-i-dera) and therefore had passed the preceding night east of the range at Lohsingh.” (Sarkar, ‘Miltary History of India’)

[12] MuT II

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Ram Sah of Mewar army forged ahead towards the Mughal centre and performed such prodigies of valour against the Rajputs of Man Singh as baffle description. Similarly the young heroes who acted as the bodyguard of Man Singh performed such exploits as were a perfect model.” – the grudging accolade that the Rajputs’ gallantry elicited out of the bigoted mulla, Al Badayuni (MuT II)

[16] According to Jadunath Sarkar ‘Rakht Talai’ (X3) was the spot where the bodies of the fallen Rajputs had been washed before cremation, not the spot where the pitched battle was fought.

[17] The Rana had been constrained to give up the advantage and charge, apprehensive as he was that if he waited too long, the Mughals would spread out infiltrating the mountainous fastness, and if they occupied the barren rocky terrain buffering Kumbhalgarh, it would be possible for the enemy to control the ground by sending in a steady stream of reinforcements from outside.

[18] “During these blazing sparks of commotion and contest, and the heat of the fires of fortune. Kuar Man Singh and the Rana approached one another; and did valiant deeds.” (Akbarnama III)

[19] Amarkavya Vanshavali, Folio 44 (b); Raj Ratnakar, Canto 7, verses 39-41

[20] Military History of India, pg. 78

[21] The Amarkavya, like Akbar’s official biography, describes the Rana and Man Singh’s approach towards each other, but the former gives more details, according to which Dodiya Bhim appeared before Man Singh and bid him ‘juhar’, thereafter the Rana moved towards him and attacked him.

[22] Badayuni (MuT II)

[23] And this is the stark lesson which stares at us: Even the deepest fidelity and unstinting bravery of the Rajputs in the service of an Islamic state, common stakes and fighting shoulder to shoulder together in life and death, failed to reach any middle-ground with the Muslims. Under no condition will the aims of Islam be diluted or the minds of Muslims be humanised to view infidels sympathetically, even as fellow human beings.

The occasional personalities who have acted at variance to this principle (an eclectic Muhammad-bin-Tughlaq, or an Akbar, or Ibrahim Adil Shah, or the Awadh Nawabs) do nothing to change the course and character of Islam. The undercurrent of deep-seated hatred against kafirs will be the dominant sentiment of Muslims in every situation and every age and in every single expression or utterance or choice. The much-hyped “composite culture” is nothing but a gross falsification of what was a fraught epoch of Indo-Islamic interactions.

This singular testimony in Badayuni’s account also illustrates the magnitude of folly of those Rajputs who collaborated with external powers for gaining limited personal advantage and stood against members of their own race fighting for independence, as also it accentuates the validity of the Rana’s principled stand: not cowering before Islamic imperialism at any cost. That it was geographically limited to the area he could control does not diminish the principle.

[24] Badayuni (MuT II)

[25] Raj Prashasti, Canto 4, Verse 25; MS Amarkavya Vanshavali, Folio 44b.

[26] “The brave warriors of the war-seeking army rushed in pursuit, and struck down many of the Rajputs.” (‘Tabakat-i-Akbari’, Khwaja Nizam-ud-Din Ahmad)

First published July 17, 2018 at Jagrit Bharat.