By Smita Mukerji

P R E F A C E

The birth anniversary of one of India’s most influential social reformers, Raja Rammohun Roy (b. 1772? – d. 1833) went past on May 22, and with it another wave of contumely dumped on him by the ‘virat Hindus’ (a term I have now personally standardised, to characterise ignorant bigots who sustain their half-educated impressions on snippet history handed around in social media and who, unfortunately, band together under the banner of resurgent Hinduism.) The extent to which such factually incorrect and utterly crass appeals to prejudice have been passed around as the ‘new patriotic narrative’ is unsettling, to say the least.

There is no doubt that the treatment of Indian history has suffered from biased portrayals of the leftist, pre-dominantly anti-Hindu academic monopolists. As a reaction to this, in recent times there has been an upsurge of the opposite kind, those intent on impetuous demolition of past icons by culling bits and pieces from sundry sources pitching these as ‘bringing out new facts for true history’. The main problem with such views is that they carry no context and singularly lack perspective. In fact they commit the same folly that leftist propagandists do in their selective portrayals to caricature Indian characters and society in advancing their agenda. To put it shortly: academic snobbery is now being met by notional lumpenry. And with no sign of an objective, insightful, factual relation of our past, we seem to have made absolutely no progress.

The slandering has gone on so long that this will have to be taken down bit by bit and therefore the start of a new series with this on Raja Rammohun Roy, the Brahmo Samaj and various aspects of the period that has been termed the ‘Bengal Renaissance’.

Quite a few well-known RW handles (some of them even considered ‘reputed’) brought their vituperations upon Roy in the last days, calling him variously a “traitor”, “sell-out”, “stooge”, a crypto-Christian convert, promoter of “atrocity literature”, “useful idiot” and agent of evangelists, one who caused the demise of ‘Indian education’ and Sanskrit, and ‘destroyed Hinduism’, etc. (Interestingly, the last of these was the charge of benighted Hindus of Rammohun’s time as well about his efforts of lifting Hinduism out of the nadir.) These opinions—and the employed phraseology—expose a curious distortion of timeline in their minds that fails to grasp a lapse of over two centuries and the significantly altered social, religious, political situation and period awareness.

We will take a look at each of these denouncements by the iconoclastic zealots, but I begin with this bit of instant twitter certitude which I caught in my feed, according to which “Raja Rammohan Roy was a great proponent of freedom of Christian Greece from Muslim Ottoman rule. But he did not want India’s freedom.” This was claimed on the strength of a scrap taken from a book[1] that quotes a line from Roy published in the Brahmanical Magazine on November 15, 1823: “Among other objects, in our solemn devotion, we frequently offer up our humble thanks to God, for the blessings of British rule in India and sincerely pray, that it may continue in its beneficent operation for centuries to come.”

The statement might seem unduly reverential towards an exploitative colonial power but has to be read in the background they were spelt out.

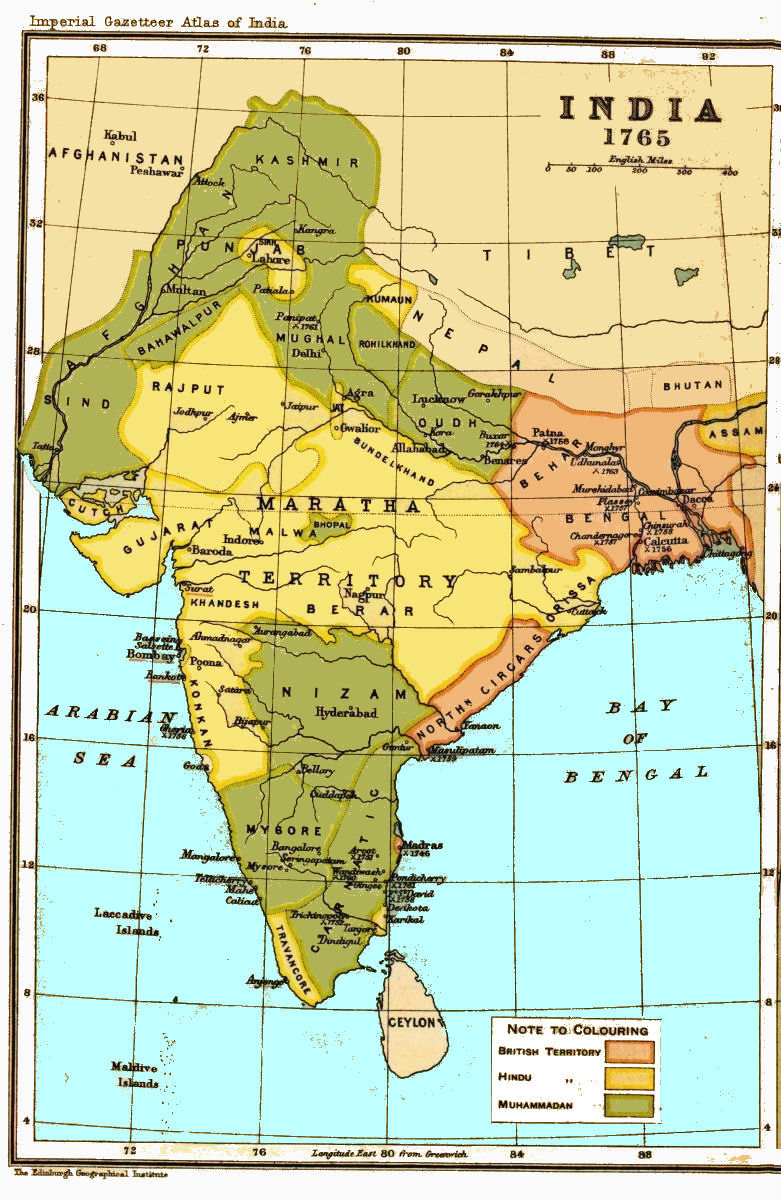

Talking about the “independence” of India in the late 18th and early 19th centuries is foolish, considering India was not a dependent nation until 1858. It was divvied up into scores of principalities and domains controlled by various powers, among them the colonies of European traders. It must be remembered that several Europeans too served in the armies of native rulers who still controlled most of India. It is a case of chronological dissonance talking of ‘nationalism’ of the post 1857-scenario not imagined back then in the absence of political unity.

Talking about the “independence” of India in the late 18th and early 19th centuries is foolish, considering India was not a dependent nation until 1858. It was divvied up into scores of principalities and domains controlled by various powers, among them the colonies of European traders. It must be remembered that several Europeans too served in the armies of native rulers who still controlled most of India. It is a case of chronological dissonance talking of ‘nationalism’ of the post 1857-scenario not imagined back then in the absence of political unity.

Bengal itself was divided into Dutch, French, Portuguese, Danish and English colonies, who grappled among themselves for control of the dozens of settlements along the Hooghly, as well as areas controlled by native Hindu and Muslim rulers, and it is important to note that it was the latter that the British had disrupted, not the former. It is similarly erroneous to describe the defection of Mir Jafar and others[2]—whatever their motivation—to the British in the Battle of Plassey as ‘treachery’ when the only entity betrayed by them was the detested nawabi, not Bengal, far less the country. The region at that time consisted of contending interest groups along the lines of which allegiances were built and broken. And the Hindu alliance with the British was more in the nature of two interests serving each-other rather than the equation of the ruler and the dominated. The arrival of the English was in fact seen as a deliverance[3] from the oppression of Islamic rule.

Let us regard the words of another person of this era, the one who gave the nation its sacred most mantra. In his novel ‘Anandmath’, the Indian writer and reformist Bankimchandra Chattopadhay (b. 1838 – d. 1894) expresses a similar sentiment:

“Do not grieve, Satyananda. You were possessed of evil spirits which helped you amass your wealth and win your victory. A sinful course can never lead to a virtuous end. Hence you will never be able to save the country. Still it’s all for the best. For, without the support of the English there is no way to revive the eternal religion.”

This was stated in more certain terms by Rammohun Roy:

“The greater part of Hindustan having been for several centuries subject to Muhammadan Rule, the civil and religious rights of its original inhabitants were constantly trampled upon, and from the habitual oppression of the conquerors, a great body of their subjects in the southern peninsula (Dukhin), afterwards called Marattahs, and another body in the western parts now styled Sikhs, were at last driven to revolt; and when the Mussalman power became feeble, they ultimately succeeded in establishing their independence, but the Natives of Bengal wanting vigor of body, and adverse to active exertion remained during the whole period of the Muhammadan conquest, faithful to the existing government, although their property was often plundered, their religion insulted, and their blood wantonly shed. Divine Providence at last, in its abundant mercy, stirred up the English nation to break the yoke of those tyrants, and to receive the oppressed Natives of Bengal under its protection. …….

I now conclude my essay by offering up thanks to the Supreme Disposer of the events of this Universe, for having unexpectedly delivered this country from the long-continued tyranny of its former rulers, and placed it under the government of the English:– a nation who not only were blessed with the enjoyment of civil and political liberty but also interest themselves in promoting liberty and social happiness, as well as free inquiry into literary and religious subjects, among those nations to which their influence extends.”[4]

Such a view was by no means uncommon among the early nationalists until as late as the 1920s, as almost all enlightened Indian leaders concerned with social reform and education, were in favour of continuance of British rule[5] for the betterment of the country. Pandit Madan Mohan Malviya (b. 1861 – d.1946), the founder of Banaras Hindu University and one of the founding members of the Akhil Bharat Hindu Mahasabha, was one of them who was of the opinion that the “British rule has done much good in India by cleansing the Indian society of its ills like the customs of sati, untouchability and child marriage.” He spoke of the “British presence in India as a blessing to Indians and we relied on the British to guide the politics of India.” They largely believed in the sense of justice, fair play, honesty and integrity of the British and saw them as a boon for India.[6] This was despite the fact that the early nationalists, after being initially humoured and tolerably received by the British government, were subsequently treated with contempt by the British rulers[7] and most of their demands denied.[8]

This might be difficult for the hyper-nationalists of today to conceive, but the idea of complete, undiluted right to self-determination as the only way for a nation to rise and attain greatness, was a gradual realisation. The early nationalists and reformers did not have the advantage of hindsight since they existed in that era. Moreover, immediately prior to the establishment of British rule, India was burdened by debilitating social and religious conditions, moral degeneracy, political instability, infirmity of governance, non-productive investments of capital on account of profligate lifestyles of the aristocracy, lack of development works and a standardised, equitable and useful education system, all of which made Indians ill-equipped and completely unprepared to meet the challenge of a rapidly modernising world pressing at its shores. We will go over these aspects in detail to put paid to each one of the refrains of the denialists who have the luxury of spouting opinions having enjoyed the education, freedoms and opportunities of modern times which was won for them by these very predecessors who they now lambast.

Swami Vivekananda put across a more holistic picture of the British government’s role in India’s transition into modern times:

“The present government of India has certain evils attendant on it, and there are some very great and good parts in it as well. Of highest good is this that after the fall of the Pâtaliputra Empire till now, India was never under the guidance of such a powerful machinery of government as the British, wielding the sceptre throughout the length and breadth of the land. And under this Vaishya[9] supremacy, thanks to the strenuous enterprise natural to the Vaishya, as the objects of commerce are being brought from one end of the world to another, so at the same time, as its natural sequence, the ideas and thoughts of different countries are forcing their way into the very bone and marrow of India. Of these ideas and thoughts, some are really most beneficial to her, some are harmful, while others disclose the ignorance and inability of the foreigners to determine what is truly good for the inhabitants of this country.”[10]

The assertiveness to demand more than the minor concessions conceded by the British and agitation for full right over their destiny grew in Indians only with time. Yet, Rammohun Roy was remarkably farsighted in this respect who saw through the imperialist design very early and questioned his British associates on the policies of the government, as we shall see subsequently.

But those were early days yet of the interactions between colonialists and the natives as the British gained control over a greater part of Bengal after the battles at Plassey and subsequently, Buxar. With the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765, Shah Alam II was forced to concede the diwani[11] of Bengal to the British East India Company. Faced with the prospect of governing the newly possessed dominion, it was a stage of exploration of ideas and experiments in governance as the English recognised that they were not dealing with a primitive society but an ancient culture with deep roots and long-established traditions.

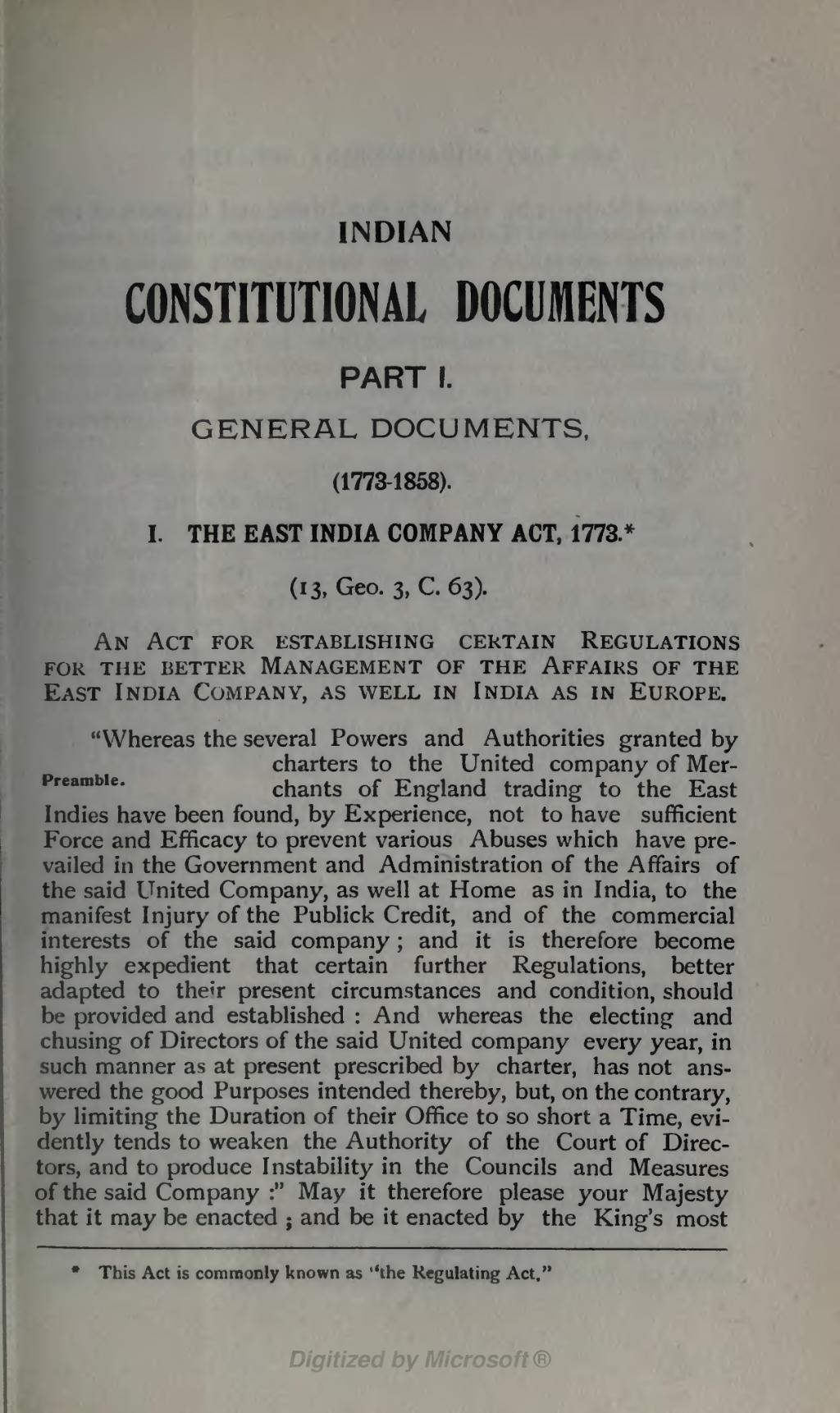

Their application of the system of land revenue administration was however more indiscriminate as the exacting taxation system imposed after 1764 stripped the land of its resources and brought untold suffering and privation to the country. As a trading company, the British East India (EIC) Company’s overwhelming concentration was on maximising its profits from the newly acquired colony and the oppressive means of its exaction by the new zamindars appointed by EIC and the inefficiency of its revenue officials in checking it, rendered the condition of the peasantry pitiable and brought on the biggest and unprecedented rural distress of 1770 that devastated Bengal[12]. This was however before the company’s practices came to be regulated by statutes of the parliament with the East India Company Act of 1773[13] and subsequently the Pitt’s India Act of 1784, which put a decisive end to the East India Company’s unconscionable, raptorial administrative system.

The English state functioned on an ‘assumed’ higher moral ground and considered matters of providing education, modern advancements and eradicating social ills in their colonies. One example of this was the determined efforts of the British to combat and abolish slave trade in its domains[14], operated by Burmese (mogs), Muslim, Dutch and Portuguese traffickers. The British until that time were sincerely interested in improving the lot of their colonies. They earnestly endeavoured to study native culture, religion and traditions to enact laws drawn at least in part from native sources of law with the idea of preserving native sensibilities and practices, and the extended debates in the parliament for passage of legislations for India demonstrate their genuine concern with the moral, spiritual and social well-being of the subject people. The establishment of a penal settlement in the Andaman Islands too was thought of with the benign intention of creating a system of reform and rehabilitation for criminals. It was in this liberal spirit of the British that Raja Rammohun Roy saw a potential to alleviate the social conditions of Bengal.

How far the British intent translated into real benefits for the colonies, the success of their interpretation of native customs in the conduct of native affairs is another matter. The full ramifications of colonial rule were still not manifest and we shall study Rammohun Roy’s response to it subsequently as and how he divined its motives, methods and impact—the first Indian to bring these out in the open quantitatively—and how these became the seeds of growth of nationalist consciousness. It was no coincidence that Bengal went on to become the hotbed of the Indian nationalist movement.

But it is important to understand that in this initial pre-colonial phase, British domination was merely military and the Indians’ association with them not in a subordinate relationship, but of two cultures taking tentative steps towards establishing acquaintance and assessing each-other and negotiating for mutual benefits. Ascribing to Indians of that time a servile mentality shows a flawed sense of the age, as this was a later phenomenon when India came to be truly dominated mind, body and spirit that produced among them sycophants and self-seeking toadies.

Rammohun describes his initial misgivings with the British and loathing for foreign presence in India, and subsequent recognition of the necessity of using the resources and the mechanisms of British administration to bring about a change in the socio-political and religious awareness of Indians:

“I proceeded on my travels, and passed through different countries, chiefly within, but some beyond, the bounds of Hindoostan, with a feeling of great aversion to the establishment of the British power in India. …….

I first saw and began to associate with Europeans, and soon after made myself tolerably acquainted with their laws and form of government. Finding them generally more intelligent, more steady and moderate in their conduct, I gave up my prejudice against them, and became inclined in their favour, feeling persuaded that their rule, though a foreign yoke, would lead more speedily and surely to the amelioration of the native inhabitants; and I enjoyed the confidence of several of them even in their public capacity.

The ground which I took in all my controversies was, not that of opposition of Brahmanism, but to a perversion of it; and I endeavoured to show that the idolatry of the Brahmins was contrary to the practice of their ancestors, and the principles of the ancient books and authorities which they profess to revere and obey.”[15]

In fact, as incredible as it may sound, at that juncture it was the English who regarded with wonderment the opulence and regality of the India’s native aristocracy and were keen on impressing upon them the benefits of their culture and rule. Rammohun Roy’s European and American friends were rather in awe of him and his views and writings on Indian scriptures had far more influence on his Western audience than the other way round. On his visit to England he was received with great fanfare, courted and honoured by all classes from the aristocrats and distinguished men of letters, to middle-class reformers and the working classes. They hosted him in their manors and their unmarried daughters and sisters were particularly attentive towards him. Religious and political thinkers sought him out for engaging in discussions, and even clergymen vied with each other for the honour of his presence at their services.[16] They speculated among themselves about his favourable turn towards their creed and claims of having won the prize of his conversion to their fold were often published by each of them. On this point Ralph Waldo Emerson remarked sarcastically that “the Unitarians have one trophy to build up on the plain where the zealous Trinitarians have builded [sic] a thousand.” But he grudgingly conceded after having met Roy: “He is one of the first scholars in India, Europeans not excepted, quite a critic in the dead European languages, and is altogether one of the first men of the age.. … This brahmin’s name is Rammohan Roy.” “In Manchester,” it was reported, “a crowd of factory workers followed Rammohun about on his tour, the men and women insisting on shaking his hand or embracing him.”[17] Moncure Daniel Conway wrote in the Open Court in 1894: “That Hindu was, in fact, as a religious thinker, without a peer in Christendom. With him began the reaction of oriental on occidental thought which has since been so fruitful.” Dr Bowring, the biographer of Jeremy Bentham, welcomed Rammohun Roy with the following words: “I am sure that it is impossible to give expression to those sentiments of interest and anticipation with which his advent here is associated in all our minds. I recollect some writers have indulged themselves with enquiring what they should feel, if any of those time-honoured men whose names have lived through the vicissitudes of ages, should appear among them. They have endeavoured to imagine what would be their sensations if Plato or Socrates or Milton or Newton were unexpectedly to honour them with their presence… It was with feeling such as they underwent that I was overwhelmed when I stretched out in your name the hand of welcome to the Rajah Rammohun Roy.” It is ridiculous to suggest that any of Roy’s acts or utterings were prompted from being in thrall of the English to warrant the use of the term “stooge” for him. It is the present day diffidence of Indians projected on him that gives rise to such a perception.

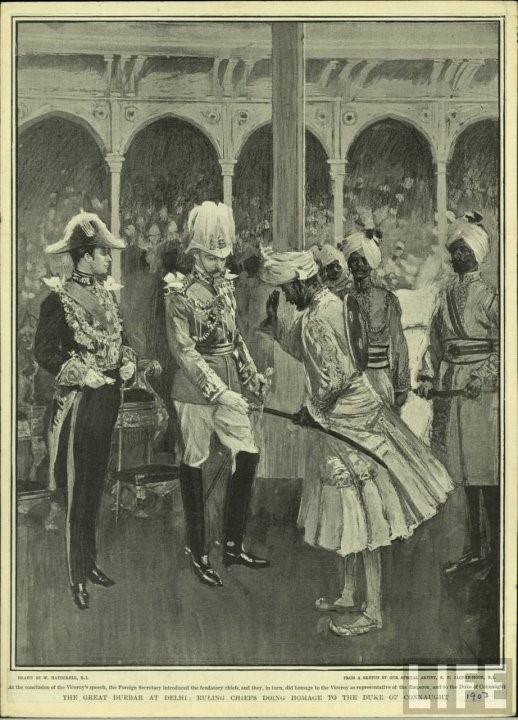

If this even juxtaposition, the Europeans’ keenness to converse, learn and absorb from India, changed in the subsequent period to imperious disregard to stamp underfoot Indians’ rights and treat them as an inferior people, it was due to the ignominious collective show of subservience at the imperial durbars at Delhi, a bevy of the best among Indians bowing in meek submission to British overlordship, that was the incipience of the idea in European minds about their own superiority.

In spite of a weakened political control, India’s socio-religious prerogative and control over narrative had been retained intact by Raja Rammohun Roy with his gigantic intellectual and scholastic prowess, cogent representation of Indian religious, cultural and economic interests and preventing the misapprehension and misconstruction of its cultural practices (including polytheism, idolatry, Hindu traditions and even ‘sati’) from being used against Indians, irrespective of the individual philosophical outlook he held out. None among the Indians in that period possessed the brilliant faculties of Roy to hold rational and logical discourse in the European public sphere given their background of developments in the sciences, philosophy and arts and letters in recent history.

India’s great intellectual traditions and scientific advancements of the classical era had all but disappeared and the nation had descended into dead habit, religious malpractices, petty infighting and proliferation of countless superstitions born of mental weakness. We are still not out of this phase of spiritual and mental decline, even if our skill-based, indoctrinating education might delude us in thinking so. We are a mass of confused, half-baked ideas and impressions and therefore egregious to attack (since this is what the recent tirade against the personality is, no critical analysis) a person of Rammohun Roy’s capacities and contributions. It is nothing short of an act of vandalism by ill-informed, boorish conspiracy theorists who know nothing better.

If among the wasteful, opportunistic Indian warlord rulership of that time, and the self-absorbed and petty religious practitioners, there were a few rare individuals who had the vision to conceive of the overarching interests of Indians as a nation, and the commensurate perspective and capability to defend India intellectually, the foremost would be Raja Rammohun Roy. And no ideologue presuming to stand for Hindus and Hinduism and using Roy to propagate their pet theories to extend their franchise in India can dislodge that.

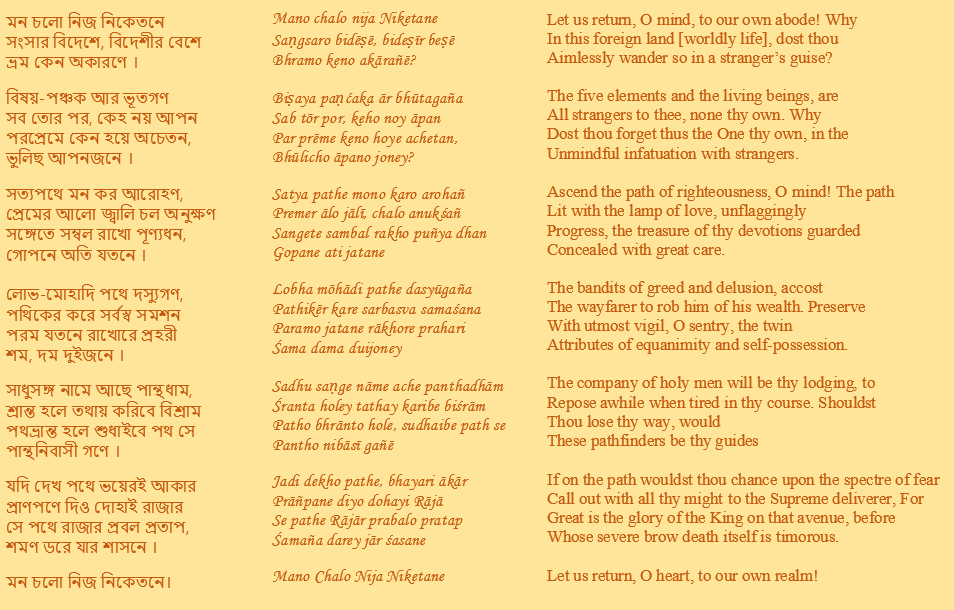

(Click picture to listen)

Cover Picture:

‘Barrackpore House’, the Governor General’s House and Park at Barrackpore (Water colour by Edward Hawk Locker-1808) (Source: British Library)

Read the next section of this series here.

[1] ‘Social, Political, Economic, and Educational Ideas of Raja Rammohun Roy’, by Poonam Upadhyaya (1990)

[2] Mahtab Chand and Swarup Chand, Umichand and Rai Durlabh, etc.

[3] Which, though actively sought by the Hindus of Bengal, did not come from the Marathas after a decade of unsuccessful attempts by the state of Nagpur to gain control over Bengal, which left it more devastated than before. There are no simplistic conclusions to be drawn from this episode either, but we will analyse this in detail on a different occasion.

[4] Petition to the King in the Council, 1823

[5] Although they all had the benefit of perspective from over half to a century experience of British rule more than what Rammohun Roy had seen.

[6] ‘Indian History’, by D. C. Bhattacharya & K. K. Ghai (2009)

[7] In 1887, the Governor-General Lord Dufferin attacked the early nationalists in a speech and ridiculed them as representing only a microscopic minority of the people. British officials criticised the nationalists and branded its leaders as “disloyal babus” and “violent villains”. – ‘The history of British India: a chronology’, by John F. Riddick (2006)

[8] ‘Raj: The Making and unmaking of British India’, by James Lawrence

[9] Refers to the status of the British in India primarily as as entrepreneurs and merchants

[10] ‘The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda’, Vol. IV

[11] Rights to collect revenue

[12] The figures of the calamity are regrettably not as easily forthcoming and descriptions of its magnitude can only be found in literature and official reports like that of Warren Hastings.

[13] Commonly known as the Regulating Act

[14] Indian (Hindu) rulers earlier, notably the Marathas, had also striven to combat and proscribe slave trade by the Dutch, the Portuguese and ‘moors’.

[15] Letter written from London to certain Mr. Gordon, 1932

(This letter, said to be an “autobiographical sketch” that appears in Mary Carpenter’s ‘The Last Days in England of the Rajah Raja Rammohun Roy’, is addressed to a person not known among Roy’s acquaintances, and is moreover not present in original. It is considered spurious by prominent biographers, including Kissory Chand Mitter and Sophia Dobson Collet. But it shows at any rate a greater keenness on the part of the English to win Roy’s favour than the other way round.)

[16] ‘Defining Christians, Making Britons: Rammohun Roy and the Unitarians’, by Lynn Zastoupil (pg. 215)

[17] Ibid.

Brilliant piece ! Nirad C Chaudhuri had similar views on Bengal Renaissance. He was an honest intellectual … fearlessly carrying “imperialist” tag hurled by lumpen Indians. Truth is beautiful, and it must be told. Congratulations!

Thank you so much!

Interesting article, Smitaji. What do you think of his alleged connections to freemasonry?