By Smita Mukerji

Read the previous section of this series here.

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Controversies were attendant on Rammohun Roy’s name as much during his lifetime as in posterity. He envisaged his native land as a self-reliant, enlightened nation and at the same time saw coincidence with British colonial interests. Was he merely a captive in the chronology of British Empire building or was he an astute thinker who used its agency to the extent it served the purpose of the betterment of his country? Judgment of Rammohun has also been influenced by changing ideas and convictions over time, glorifying him one instant and dissing his achievements in the next, each commemorating his life to reinforce their respective cultural and ideological agendas. But much of these conflicting perceptions arise from substantial gaps in information about Roy.

A surfeit of myths and legends grew around his personality, many of which find their origin in his biographies by those who had made his acquaintance but had little to no direct access to intimate details about his life, which makes it difficult to separate truth from the fiction it came to be enveloped with. What these numerous writings on Roy do however affirm is the irrefutable fact that he was among the most influential thinkers in the world that time and one of the tallest personalities of the era, and it is indeed unfathomable that so little about him finds its way into textbooks on 18th–19th century history of India.

The earliest writings on Roy were short sketches by individuals known to him, mostly English writers. The first of these was by John Digby[1], a Bengal civilian and Roy’s friend, who had also been his employer[2]. More biographical works appeared following his death, among them one by Sandford Arnot, who had been Roy’s personal secretary; by James Sutherland, editor of the Calcutta-based ‘Bengal Hurkaru and Chronicle’, who had been the Principal of the Hooghly College and was Roy’s co-passenger in the journey to England; and by Lant Carpenter (b. 1780 – d. 1840), a Unitarian minister of Bristol, where Roy was to spend his last days. Carpenter authored two other books on him: ‘A Review of the Labour, Opinions and Character of Raja Rammohun Roy: In a Discourse on the Occasion of his Death’ (1833) and ‘A Biographical Memoir of the Late Raja Rammohun Roy, together with a series of extracts from his writings’ (1835). The Unitarians’ interest in Roy also produced some memoirs and sketches, notably Robert Brook Aspland’s (b. 1782 – d. 1845) ‘A sermon on the occasion of the lamented death of Rajah Rammohun Roy with a biographical sketch’ (1833) and Rev. William Johnson Fox’s (1786–1864) ‘A discourse of the occasion of the death of Rajah Rammohun Roy’ (1833). More detailed biographical accounts came up a couple of decades later, like ‘The Last Days in England of Raja Rammohun Roy’ (1866) by Mary Carpenter (b. 1807 – d. 1877), and ‘The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy’ (1900) by Sophia Dobson Collet (b. 1822 – d. 1894).

Though most of these writers wrote from first-hand information, these suffer from some defects, mainly due to the fact that they read and understood the person in the light of their own predispositions. For one, they were more enthused by his religious thought than any other aspect of his life or work.[3] Mary Carpenter, in particular, who was otherwise involved in social causes like women’s suffrage and the rehabilitation of poor juvenile offenders, writes little about Rammohun’s deep concern with the social status of Hindu women. Her overwhelming preoccupation instead was to prove somehow that Rammohun had willingly converted to a ‘reformed Christianity’.[4]

The other shortcoming in these accounts is that they do not make use of any of the Bengali sources on Roy. They are sparse on particulars on Roy’s early life, the little that they contain based on indirect information mostly gathered from anecdotes and hearsay from Roy’s friends and co-workers[5], none of which may be regarded as consistently objective. Differences of opinion within the Brahmo community itself about the legacy of their founder moreover led many to question their authenticity. These discrepancies are reflected in Sivanath Sastri’s (b. 1847 – d. 1919) monumental work ‘History of the Brahmo Samaj’ (1911–12).[6] It was possibly for these internal disagreements that the Brahmo Samaj was reticent in coming out with a standard biography of Rammohun Roy. This led to some of the English biographers assuming an air of being original and authoritative more than they actually were.[7]

It is strange that no life-sketch of Rammohun Roy was attempted by an Indian until 1845, when Kissory Chand Mitter’s (b. 1822 – d. 1873) biographical essay was published in the ‘Calcutta Review’ (vol. 4, no. 8). Mitter apparently possessed the means to obtain information from close friends and co-workers of Roy which lent to his essay a ‘startling originality’[8]. Most importantly, he was the first biographer to point out that the English writings attributed to Rammohun Roy were not entirely his, and that at any rate he spoke better English than he could write. This view is held among others by S. D. Collet as well. He was also the first who disputed Roy’s credentials as a Vedantist, which caused some vexation among the Brahmo community. Mitter’s portrayal of Roy was of a ‘culturally neutral, philosophical theist’[9], a characterisation remonstrated in the first ‘insider’s view’ produced by the Samaj a few decades later with Nagendranath Chattopadhyay’s ‘Mahatma Rammohun Rayer Jeeboncharit’ (1881). Though considered a literary classic, it did not provide any extraordinary insights.[10]

The most authentic reconstruction of Rammohan Roy’s life was by historian and Bengali literary critic, Brajendranath Bandopadhyay (b. 1891 – d. 1952), which appeared in the form of a series of biographical essays and articles published between 1926 and 1946, thirty-five in number[11], covering various aspects of Roy’s life. Bandopadhyay was the first to go beyond transmitted facts and fables and scrutinise authentic documents available on Rammohun Roy.

Reliable information on Roy’s life, assets and personal career first came to light in the course of the case filed against him by his nephew[12], Govinda Prasad, before the Equity Division of the Supreme Court at Calcutta, in 1817. The testimonies of Rammohun himself, and his friends, relatives and employers, summoned during the litigation, together with the records of the Boards of Revenue Proceedings for 1817 and the years thereafter, constitute the indubitable sources of information on Roy upon which Bandopadhyay based his writings. His findings[13] discount several of the fables related in Roy’s biographies.

E A R L Y L I F E

Just a little after Warren Hastings’ elevation as the Governor-General of Bengal[14], Rammohun Roy was born to an affluent kulina Brahmin family in 1774[15], in Radhanagore, in Hooghly district of West Bengal. His great-grandfather, Krishna Chandra Bandopadhyay had been conferred with the title ‘Ray-i-Rayan’ on account of his service with the Mughal administration in Bengal. Rammohun’s grandfather, Braja Vinod Bandopadhyay, had similarly been in the employment of Nawab Alivardi Khan of the independently carved out state of Bengal. Of his seven sons, the fifth, Ramkanta Bandopadhyay, was Rammohan’s father, and had served the Bengal nawabs at Murshidabad. Since Ramakanta had been childless from his first marriage with Subhadra Devi, he was married to two other women. Rammohun, his elder brother Jagmohan and a sister—whose name is unknown—were born to him by Tarini Devi, and another son by name Ramlochan, with his third wife, Rammoni Devi.

There is a widespread image of Rammohun Roy as having been a tireless wanderer for the greater part of his life. Bandopadhyay’s pioneering research on his life however led to the most surprising finding that he had not been away from home at any point of time for several years at a stretch.[16] According to one longstanding fable, after having studied for some years at a local pathshala he had been sent off to Patna to master Persian, Arabic and Islamic studies, and thereafter to Varanasi to study Sanskrit and classical Hindu tradition. But on scrutinising the sources closely this appears to be a very unlikely story. If as Ramakanta’s son he was expected to follow on his ancestor’s footsteps, there is no plausible reason why his elder brother, Jagmohan, would be excluded from receiving similar training outside Radhanagore. From all appearances, knowledge of Persian was locally available, considering Roy’s father and forefathers were proficient in Persian—having traditionally served in Muslim courts where this would have been a mandatory requirement—and not known to have travelled any appreciable distance to gain such competence. But even from all this, the need for acquiring knowledge of Arabic is wholly inexplicable and appears far-fetched.

Likewise, it is from the Baptist-turned-Unitarian minister and a close friend of Rammohun, William Adam (b. 1786? – d. 1881), that we hear about his stay in Varanasi for as long as ten years, which however does not at all fit chronologically with the sequence of events in Roy’s life. Moreover, this would make him a Hindu scholiast which Rammohun was not. In Brajendranath Bandopadhyay’s assessment, the first fourteen years of Rammohun’s life were spent entirely in Radhanagore. Like his father, Rammohun was also married thrice, the first time in 1781. But this wife died almost immediately. Adam informs us that thereafter Ramakanta got him married twice in quick succession within a space of a year (1781–82). After he turned fourteen, Rammohun was put under the tutelage of a local Brahmin called Nanda Kumar Vidyalankar (b. 1762 – d. 1832).[17] It was from Vidyalankar that he received instruction on Sanskrit and the scriptures and he is also said to have been Rammohun’s guru, having initiated him formally into tantra.

According to another bit of yarn that emanated from Lant Carpenter,[18] Roy travelled to Tibet with the purpose of studying other religions closely. There, having antagonised local lamas with his views he was hunted, when the kindly help from a Tibetan woman rescued him from their wrath. But no such explicit mention can be found in any of Roy’s writings. In his first book ‘Tuhfat-ul-Muwahidin’ (1803–4), where one might expect the event to be recorded among his life experiences, he merely mentions having visited ‘distant lands, some of which were flat plains and some mountainous’. But this is too indistinct to assume any truth in Lant’s story. Such unverified anecdotes about Roy inevitably served to create an impression of him being an adventurer and a fearless crusader. Mary Carpenter even composed an enchanting poem[19] based on this fanciful tale hinting that Rammohun’s energetic efforts later for the emancipation of women had been on account of this assistance that he had once received from a woman in a hostile land.

In reality, Rammohun’s concern and empathy for females had much profounder basis than the singular experience of a youthful solivagant would produce. It was rather born of a deep veneration for Indian womanhood which he expressed in his appreciation of the values underpinning the mythology of ‘sati’, explaining that the custom sprung from a presumption of “the superiority in the cosmos of the feminine principle over the masculine and recognised the woman’s greater loyalty, courage and firmness of spirit.”[20] His opposition to the custom was merely as a humanist, not contempt for the rite or an urge to subvert the ethos at its base. We shall of course look in greater detail into his quest as the celebrated ‘sati abolitionist’ in later sections of the series. But it would be pertinent to mention another interesting fact: In the decades after his death, Rammohun Roy’s individual fame, whether as a crusader or a thinker, had grown unrelated to the institutions he founded. Quite unlike the portrayals by his English biographers, by the end of the 19th century, as the conservative backlash gained ground among educated Bengalis against the assault on their religion, his reputation was not so much as a reformer but that of an upholder and rightful custodian of uninterrupted Hindu tradition. In contrast, the Brahmos came to be viewed as a ‘sad caricature deeply alienated from their ancestral Hindu faith’. While their progenitor drew praise for his ‘consistently respectful attitude towards canon and scripture’, the Brahmos were regarded as a misguided community who favoured state-sponsored social legislation.[21]

Another abiding myth about Rammohun has been that he was disinherited by his father on account of his sacrilegious religious views. But facts borne out from legal records clearly belie this figment which traces back to Sandford Arnot. Ramakanta possessed considerable acumen in management of assets and creation of wealth and had trained both his sons, Jagmohan and Rammohun (Ramlochan was apparently too young, being born much later), in honing their business skills. Earlier in 1791, he had moved his family from the ancestral home in Radhanagore to set up an independent estate in Langurpara or Nangurpara, and procured additional holdings, among them, a nine-year lease in Bhurshut pargana and purchased a taluka in Harirampur, with his eldest son Jagmohan standing as guarantee. From a letter written by Rammohun himself during this period (March 22, 1796) it is apparent that he was equally involved in the management of his father’s estates. In December 1796 the same year, Ramakanta divided all his assets among his three sons, save a small house in Burdwan that he kept for himself. In lieu of the taluka purchased earlier on Jagmohan’s name, it appears Ramakanta left him a house in Jorasanko (North Calcutta). His total share of property gifted by his father and that inherited from his maternal grandfather is estimated to have exceeded 90 bighas. Such popular fiction as his ‘disinheritance’ was invented by those for whom it was useful to portray him as a religious eclectic and a rebel.

After the division of his property, Ramakanta moved to Burdwan (Bardhaman) from where he managed his own estates, and as mokhtar (agent) supervised those of Rani Bishnu Kumari, the queen mother of the Burdwan royal family. Rammohun’s stepbrother Ramlochan, accompanied by his mother Rammoni Devi, moved back to Radhanagore, which remained their residence until his untimely death in 1810. Tarini Devi, with her elder son Jagmohan and his family, and Gurudas Mukhopadhyay, her grandson from the daughter married to Sridhar Mukhopadhyay, stayed in Langurpara.

Rammohun himself was in this period looking to expand his assets and appears to have made his first travel to Calcutta somewhere in the third quarter of 1797 for conducting business. Around this time he loaned a British civilian by name Andrew Ramsay, an amount of Rupees 7,500. Far from any signs of severance of ties with his father, he was in this time still supervising Ramakanta’s estates in Bhurshut (until 1799). In 1799, he acquired the talukas of Govindapur and Rameswarpur, and owned four other patni talukas apart from his inherited assets. Around mid-1800, Rammohun travelled to ‘Patna, Kashi and places distant from Calcutta’ entrusting the management of his estates to a friend called Rajeeb Lochan Ray. But the grounds for the travel was purely to secure some lucrative business or an employment.[22] The visit was a short one and he returned to Calcutta the following year and this time stayed there close to two years[23], the first time he camped away from his landed estates for any significant length of time. This also appears to be the time that he used his acquaintance with Islamic scholars and theologians employed by the sadar diwani adalats and Fort William College[24] to augment his knowledge of Persian, Arabic and Islam. He gained such mastery in the fields that some of these scholars referred to him as a ‘zeburdust maulvi’. This was not, as is the common belief, owing to some formal course of study in Patna.

He steadily expanded his network of clients and patrons and also extended a loan of Rupees 5,000 to his second European creditor, Thomas Woodford, with whom he was employed for a brief length of time (March to May 1803) when the latter was posted in Dacca Jalalpur (now Faridpur). This can also be seen as the beginning of his growing roots in the imperial city though he did not settle down there until after 1814.[25]

There is yet another prevalent myth about Roy that he was in the employment of the British East India Company for the nine years of his association with John Digby (1805–14). But in reality his engagement with the company was for short spells, altogether not more than two years. He was a temporary seristidar (Persian term for keeper of records) at the fauzdari (police) court in Ramgarh (August to October, 1806) and thereafter in Bhagalpur. 1809 onwards, he served as diwan to Digby in Rangpur, during the latter’s appointment there as Collector.

It is important to know that these stints of Indians working with Europeans, or in this case the British, referred to as “employment” were not the same as perceived presently in the sense of a subordinate serving under a superior, but what in today’s parlance could be referred to as ‘consultancy’, in the nature of temporary, contractual engagements as local advisors. E.g. Roy’s contemporary, Raja Nabakrishna Deb (b. 1733 – d. 97)[26], a well-heeled businessman and forbear of the Sovabazar royal house—that came to be at the forefront of Calcutta’s conservative Hindu society and provided the main impetus to the Dharma Sabha, which famously put up a strident resistance to the outlawing of sati and opposed the Hindu Widow Remarriage Act—was employed as Warren Hasting’s Persian teacher in 1750 and had also accepted an appointment as the munshi (administrative clerk) of Governor Drake. This should silence the bilge about Roy being a “stooge” of the British on account of the assignments he variously took up with them on occasions. It was customary for the British government—which was not yet the oppressive machinery of later times—to invite cooperation from among the distinguished gentry of Calcutta to assist in various administrative tasks and advise in native affairs, because until then they had not developed a trained, formal administrative force knowledgeable about local customs and languages.

Digby who apparently held Roy in high regard was keen on hiring his services on a more enduring basis. But what prevented this was a certain hostility that the Board of Revenue in Calcutta bore towards him. Though the officially cited reason for not approving his services was that, just as a seristidar in a fauzdari court he was not expected to have adequate knowledge of revenue matters, Bandopadhyay’s study of the records turned up an interesting circumstance. What he found noted in the margins of the relevant documents was that the President of the board had occasion to hear “unfavourable mention of his [Rammohun’s] conduct.” During his earlier engagement at Bhagalpur, Roy had stoutly defied an ill-mannered English civilian called Sir Frederick Hamilton for hurling abuses at him, and following this likely been marked as persona non grata by the company.

Bandopadhyay’s painstaking research made it possible to cast aside several of the reported episodes commonly associated with Roy. We will look at some more of these in the subsequent sections, and also take a look at what in the meanwhile had transpired in Rammohun Roy’s private life. At what point did relations sour with his family and why?

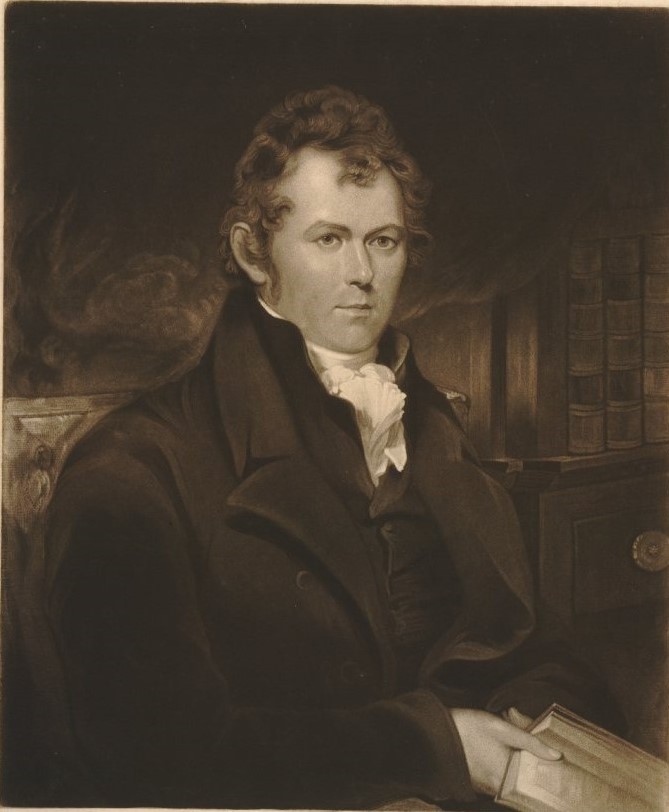

Cover Picture:

Portion of the crumbled ancestral house of Raja Rammohun Roy in Khanakul, Radhanagore (Source: Arambagh Blog)

[1] He was also the one who first got some of Roy’s works (translation of ‘An Abridgement of Vēdāṇta’ and the Kēnōpaniṣad) published.

[2] This reveals the nature of the relationship between Roy and his British associates, which was as between coequals, and that with his bearing and intellectual prowess he patently commanded the latter’s high estimation.

[3] Collet was, for instance, associated with the ‘Emerson Circle’, an association named after Ralph Waldo Emerson of American Transcendentalists, a movement which drew heavily from Hindu philosophy, especially the Upanishads. She was also a keep opponent of the rising atheist thought in contemporary England represented by some key personalities like George Jacob Holyoake (b. 1817 – d. 1906).

Roy’s influence on the new religious movements in the West, both in England and across the Atlantic in America, and how it shaped the ideas of Victorian society will be discussed in detail later.

[4] Kissory Chand Mitter in his review of Carpenter’s book which appeared in The Calcutta Review, vol. 44, no. 87, 1866: 119-33

[5] Collet’s work was refurbished to a great extent with details added by Calcutta-based Brahmos, and its second edition was improved substantially by the Brahmo theologian, Hem Chandra Sarkar.

[6] Sastri’s own work was found to be erroneous on some points, which in turn relied heavily on the work of S. D. Collet, whose main informants had never met Roy personally or known him.

[7] This is particularly true of Mary Carpernter who made changes to her work, initially admitted to be a compilation at the insistence Indian friends, but this mention omitted in the subsequent editions. She later was obliged to tone down her unwarranted claims after her visit to India and meetings with the Brahmos.

[8] Amiya P. Sen (‘Rammohun Roy: A Critical Biography’)

[9] Ibid.

[10] Its value is limited since the initial editions contained no analysis of Roy’s religious and political outlook. A later edition did include an analysis on this, but by Brajendranath Seal, not the author himself.

[11] Of these three (2 in English and 1 in Bengali) entirely devoted to Roy’s early life.

[12] Son of Rammohun’s elder brother, Jagmohan

[13] In subsequent writings like ‘Selections from Official Letters and Documents relating to the Life of Raja Rammohun Roy’ (1938) by Ramaprasad Chanda (b. 1873 – d. 1942) and Jatindra Kumar Majumdar; and ‘Raja Rammohun Roy and the Last Mughals’ (1939) by Majumdar, much of these findings are confirmed, though claimed as ‘new facts’ brought in public for the first time.

[14] With the Regulating Act, the Bengal Governorship was enhanced to Governor-General of India and the presidencies of Madras and Bombay were subsumed to the Government of Bengal. It put restrictions on unrestrained commercial activities of the East India Company and provided for the institution of a formal judicial system with the establishment of the Supreme Court in Calcutta.

[15] The year of his birth remains contested. By the contending view, he was born on May 22, 1772 which, in deference to the date officially accepted by Brahmo Samaj, is observed as his birth anniversary. The assumption of this date is however based on rather thin peripheral evidence. The year 1774 is inscribed on the tablet placed on Rammohun Roy’s tomb in Arno’s Vale cemetery in Bristol, fixed a few decades after his death, in 1872, and “nothing but the strongest positive evidence should induce us to believe that a monument on the burial ground erected by or on behalf of the descendants of Rammohan Roy and explicitly referring to the sorrow and pride with which his memory was cherished by them, would bear a date of birth without their sanction and different from the tradition current or accepted by them on good authority.” (Lecture: Date of Birth of Rammohan Roy, in ‘On Rammohan Roy’, by Dr. R. C. Majumdar) From a strictly historical point of view, 1774 must be accepted as the year of Rammohun Roy’s birth.

Historian Brajendranath Bandopadhyay too held that the evidence of Rammohun being born in 1774 is more compelling. He deduced this based on John Digby’s testimony who noted in 1817, when he was publishing some of Rammohun’s works from London, that the latter was forty-three years old at that time and that their first meeting had been when he was only twenty-seven. Digby arrived in India in 1800 and likely met Rammohun the following year in 1801. This matches Digby’s statement about Roy’s age. If Rammohun had been born in 1772, he would be twenty-seven years old in 1799, a year before Digby set foot in India.

[16] S. D. Collet similarly expressed scepticism on tales of Roy’s lengthy wanderings from home.

[17] He was a teacher who would later in life take to tantra sadhana and came to be known as ‘Hariharananda Kulavadhuta’.

[18] Carpenter claims that he heard Roy confess that at fifteen he had set out to visit Tibet.

[19] “Exiled from home eve’n in thy earliest youth, the healing balm of woman’s love was pour’d nto thy troubled breast: and thence were stor’d deep stirrings of gratitude and pitying ruth—to lead thy race to that primeval truth.” ~ Mary Carpenter

[20] Rammohun Roy (quoted in ‘Sati as Profit Versus Sati as a Spectacle: The Public Debate on Roop Kunwar’s Death’, by Ashis Nandy-1994)

[21] Amiya P. Sen

[22] Andrew Ramsay, his first European creditor, is known to have been officially posted in Benaras in this time.

[23] This is borne out from the fact that as of early 1803, he was employed in Dacca-Jalalpur, with Thomas Woodford as diwan or revenue assistant.

[24] Also called the College of Fort William, it was an academy and learning centre of Oriental studies established by Lord Richard Colley Wellesley, then Governor-General of British India. The law to establish its foundation was passed on May 4, 1800, to commemorate the first anniversary of the victory over Tipu Sultan at Seringapatam. It was founded on July 10, 1800, within the Fort William complex in Calcutta. Thousands of books were translated from Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Hindi, and Urdu into English at this institution.

[25] In a petition submitted by him on April 12, 1809 to the Governor-General Lord Minto, Rammohun presented his credentials with the statement that his antecedents and attributes could be verified from officials of the the sadar diwani adalats and Fort William College in Calcutta, implying that he was thoroughly familiar with the city, its institutions and circles before he finally settled in Calcutta. Digby repeated this information in Roy’s introduction when he recommended him to the government for confirming the latter’s services with him in 1810.

[26] It was from the British that Nabakrishna Deb earned the title of ‘Maharaja Bahadur’ and it is established beyond reasonable doubt that along with Mir Jafar, Jagat Sheth, Omichund and Krishna Chandra Roy, Ram Chandra Roy, and Ali Beg, Nabakrishna Deb had been instrumental in the plot against Nawab Siraj-ud-Daulah. It would be instructive to know that his successor, Gopi Mohun Deb (b. 1798 – d. 1847), who was founder of the Dharma Sabha, was one of the first five founder members and Directors of the Hindu College along with David Hare and others, and was given title of ‘Raja Bahadur’ by the British.

supeb, i saw Raja Ram Mohan’s house in Kolkata was remembered all over again The 17th Century and the 18th Century Kolkata was very interesting, the time of the foundation of the new India and the British Raj (BANMALI SARKAR, GOVINDRAM, UMMICHAAND ,NAKUDHER, JAGAT SETH, MATHUR SEN, , RAJA RAM MOHAN , WARREN HASTINGS &&&&&

http://nithinkscom.wordpress.com .