By Smita Mukerji and Swapnil Hasabnis

History is determined as much by narration as by the facts constituting it. In fact, the former often has greater bearing as the latter can be manipulated to convey a picture completely removed from the actual reality of a past event or person. Indeed, almost all historical personalities and events have been shaped by the perceptions and motivations of the people describing them. Consequently, a historical personality can transmogrify to a completely different character depending on the sensibilities and ideologies of the time in which and people by whom (s)he is regarded. A religious revivalist mutates into a ‘reformist’ customised to the needs of another age, and the father of Hindu nationhood becomes a ‘secular’ icon suited to the agenda of a degenerate modern secular state…

An article in Print.in titled ‘Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, who championed a ‘Hindavi Swarajya’, wasn’t against Islam’ recently came up with the claim that “Many have championed him as an “important part of Hindu nationalist ideology”, but the truth is that his relationship with Islam and Muslims is not so black and white.” We scrutinise here some of the claims put out by the author, Taran Deol, to support his position.

Deol states: “What historians say

The earliest use of the term Hindu can be traced back to a letter, allegedly from Shivaji to Dadaji Naras Prabhu Deshpande of Rohidkhore on 17 April 1645 where he wished for Hindavi Swarajya. While the authenticity of the letter is contested, the interpretations of the term are also varied. Scholar Wilfred Cantwell Smith translates it to “Indian independence from foreign rule” and historian Pagadi views it as “Indian rule”. However, religious studies scholar William Jackson takes it a step further, stating it means the “self-rule of Hindu people.”

This is however a misrepresentation. Even though the authenticity of the letter from a young Shivaji to Dadaji Narasprabhu Gupte dated April 17, 1645, may be questioned, all it really puts in doubt is the point of time when Shivaji consciously articulated this vision. But historians are unanimous in their assessment that Shivaji amply affirms this principle at every step of his struggle in first establishing himself and later the ideals on which he founded the Maratha state and in his dealing with other dominant powers of the time. What it does prove beyond doubt is that the expression of ‘Hindavi Swarajya’ was in circulation much before it came to be used as a byword for the Indian nationalist movement, and was one of the defining objects of the Maratha Empire.

Scholars have variously attempted to explain the term “Hindavi Swarajya’ in the past but much of these views were formed in the background of the extended experience of a completely disempowered and enslaved nation under the British, and therefore interpreted as a limited goal for achieving self-rule. But the situation of Hindu rulers during Islamic rule was not of abject dependence but one in a subordinate relationship in power. Taken in its correct context the term assumes an entirely different implication: it was the emphatic vision of ‘Hindu paramountcy’. An accurate interpretation in Hindi/Sanskrit to explain the term would be: ‘हिन्दू आधिपत्य’ or ‘हिन्दू प्रभुत्व’. It was an assertion of the ascendance of Hindus in the lands of their ancestors, primacy of their civilisational ethos, religious values and cultural expressions to eradicate the corrupting and degrading influence and ignominious subordination to Islamic rule. And there is not a single act in the career of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj that deviated from this vision. In fact, it was reinforced repeatedly through numerous acts some of which are described in this talk by Smita Mukerji.

This is better illustrated in another term coined subsequently for describing the character of the Maratha state by an illustrious exponent of the Maratha empire, Peshwa Baji Rao: ‘Hindupadpatshahi’, a term declaring total prepotency of Hindus. In fact, Chhatrapati Shahu came to be referred in that time as ‘Hindupati’ or ‘king of the Hindus’. The usage of this term for the Maratha ruler traces to the time of Shivaji himself as we find in a letter dated February 13, 1659, from a factor of the British East India Company in Rajapore, Henry Revington, written to Shivaji, where he refers to the latter as the “General of the Hindu Forces”.[1] The fact that this was apparent to a neutral observer like Revington puts it beyond the scope of doubt that ‘Hindavi Swarajya’ in the sense used to describe the vision of the progenitor of the Maratha state was solely visualising a pure Hindu state.

Deol quotes author and historian, Manu S. Pillai to make his case: “All this was certainly a rejection of an existing system of power built on Islamic ideals, but it does not appear to be a mark of hatred for that religion itself.”

This is but self-evident. No part of Hinduism or a state built on Hindu ideals can possibly bear “hatred”, negate or persecute a person of a different faith. Shivaji’s vision of a pure Hindu state was not necessarily hostile to Muslim inhabitants of the land, unless their usual tendency of offence and imposing their religious framework interfered with it. Shivaji did not permit any Islamic custom in his dominions which was at odds with Hindu values.

The term often has been used interchangeably with ‘Hindupadpatshahi’, ‘Hindu dharma’ or ‘Maharashtra dharma’—since the ‘dharma’ of the Marathi people is Hindu—by latter day Maratha rulers, regional chiefs and sardars.

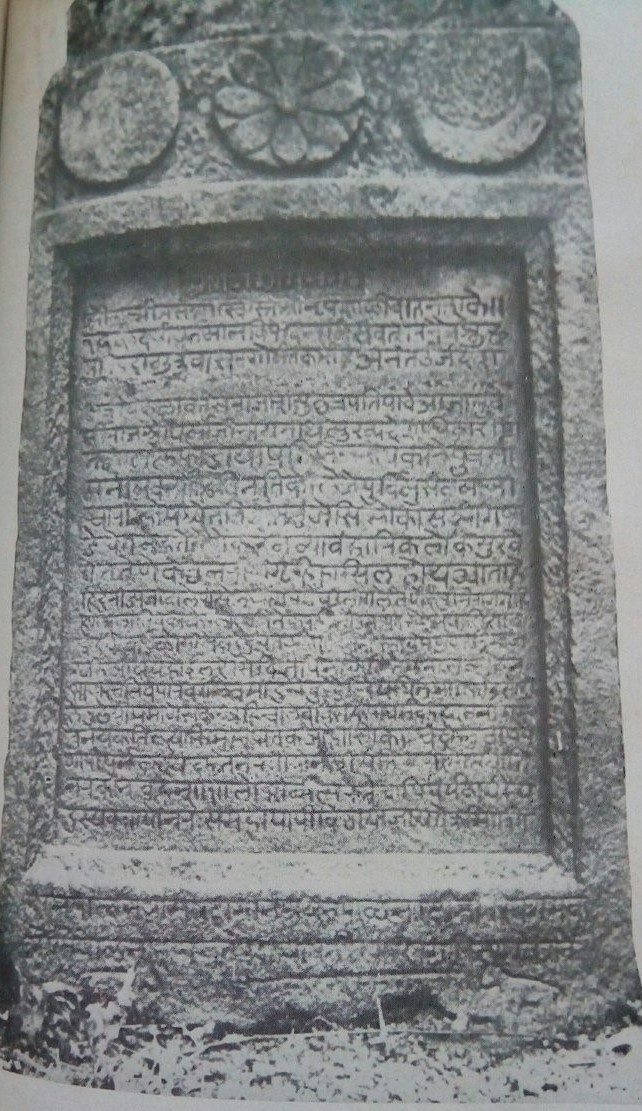

An unambiguous reiteration of this vision of Shivaji, can be seen from an inscription of 1688 CE by his son and successor, Chhatrapati Shambhaji, found in Village Hadkolan in Goa. The inscription which has cow and lotus emblems on it, was laid after the Marathas successfully annexed the area, proclaiming the establishment of his dominion with the words, “…Now this is under Hindu rule”[2], and announced the abolition of undue taxes imposed on Hindus.

The concept of Hindu sovereignty is eloquently described in the rousing composition[3] by the contemporary poet Bhushan on Shivaji, feting him as a divine incarnation who had come to redeem the land from mleććhas (a term to describe Muslims).

Clearly, the interpretations of Smith and Pagadi do not stand up to scrutiny against contemporary sources on Maharaj Shivaji.

Deol quotes another line from Pillai, citing “the Maratha king’s familial and ancestral relation with Muslims and the changes this led to in his courtroom and style of diplomacy.”

He however ignores a key fact, that of Shivaji’s continued defiance to the Adilshahi ruler and Shahji’s consequent disavowal of his son and his mother, Shahji’s first wife, Jijabai.

This refers to Shivaji’s takeover of Kondana fort and refusal to surrender it, defeating the Bijapur forces sent to recover it, following which Shahji was arrested from Jinji in order to force a negotiation on Shivaji to relinquish the fort. Although he had to give in before Mohammed Adil Shah’s blackmail for securing his father’s release, Shivaji had clearly set out on a course to carve out an independent state and not continue along the lines of the allegiances of his father. That this mission had the blessings of his mother, the inspirational matriarch of the Maratha state, at the cost of continued estrangement from her husband and enduring a lonely hard battle standing by the side of her son, also shows a marked divergence in the prospects they had in mind from Shahji’s generalship in the service of the Adilshahi rulers. Shivaji may not have been clear at that point how exactly and when he was going to achieve his aims, but his repudiation of an easy career hobnobbing with Islamic powers is unmistakable. On the part of Shahji it may be said, that in his position he had little power to change the commitments and choices he had made in his life. The father and son were of different element and spirit.

“Shivaji’s father, for one,” writes Deol further, “was named to honour a Muslim saint called Shah Sharif – while Shahji bore the first part of the pir’s name, his brother took the second and was called Sharifji…”

Deol tries to peddle his myth reinforcing it with another myth. This popular story, which surprisingly some career historians have also repeated, goes like this:

Shivaji’s Grandfather, Maloji Raje, being childless, had prayed for sons at the dargah of the Sufi saint Shah Sharif in Ahmednagar. The sons he obtained as a result of his devotions had hence been named after the said saint.

This enchanting tale may make many of those who dwell in the romance of India’s famed (rather fabled) composite culture misty-eyed, but is unfortunately just that: a tale.

Though it is true that Maloji Raje was an officer of the Nizam Shah of Ahmednagar, the facts relating to his supposed association with Muslim saint are rather disappointing for our composite culture enthusiasts.

Shahji Raje was born in 1601 CE His brother Sharifji was born in the year 1603 CE (Historian G. B. Mehendale gives his date of birth as March 16, 1599, and that of his brother about two years later in 1601 CE)[4] We come to know from a farman of Murtuza Nizam Shah II, that the ‘Pir’ Shah Sharif died somewhere between 1603 and 1604 CE. It was not a practice in Hindu families of those times to give names of living people to newborns. Moreover, the name ‘Shahji’ had already been in use in Shahji’s maternal family, the Nimbalkars, one of the predecessors being named ‘Shahji Nimbalkar’. The name also figures in several other letters preceding the time of Shahji. Historian Vasudeo Sitaram Bendrey writes in his book ‘Maloji aani Shahaji Maharaj’ that the name Sharifji was in use in the Bhosale family before the birth of the sons of Maloji, citing a letter of year 1568 naming one Sharifji Bhosale.[5] It is common practice in many Indian families of naming children after predecessors. Inasmuch, the claim that Maloji’s children were named after the Muslim pir would appear baseless.

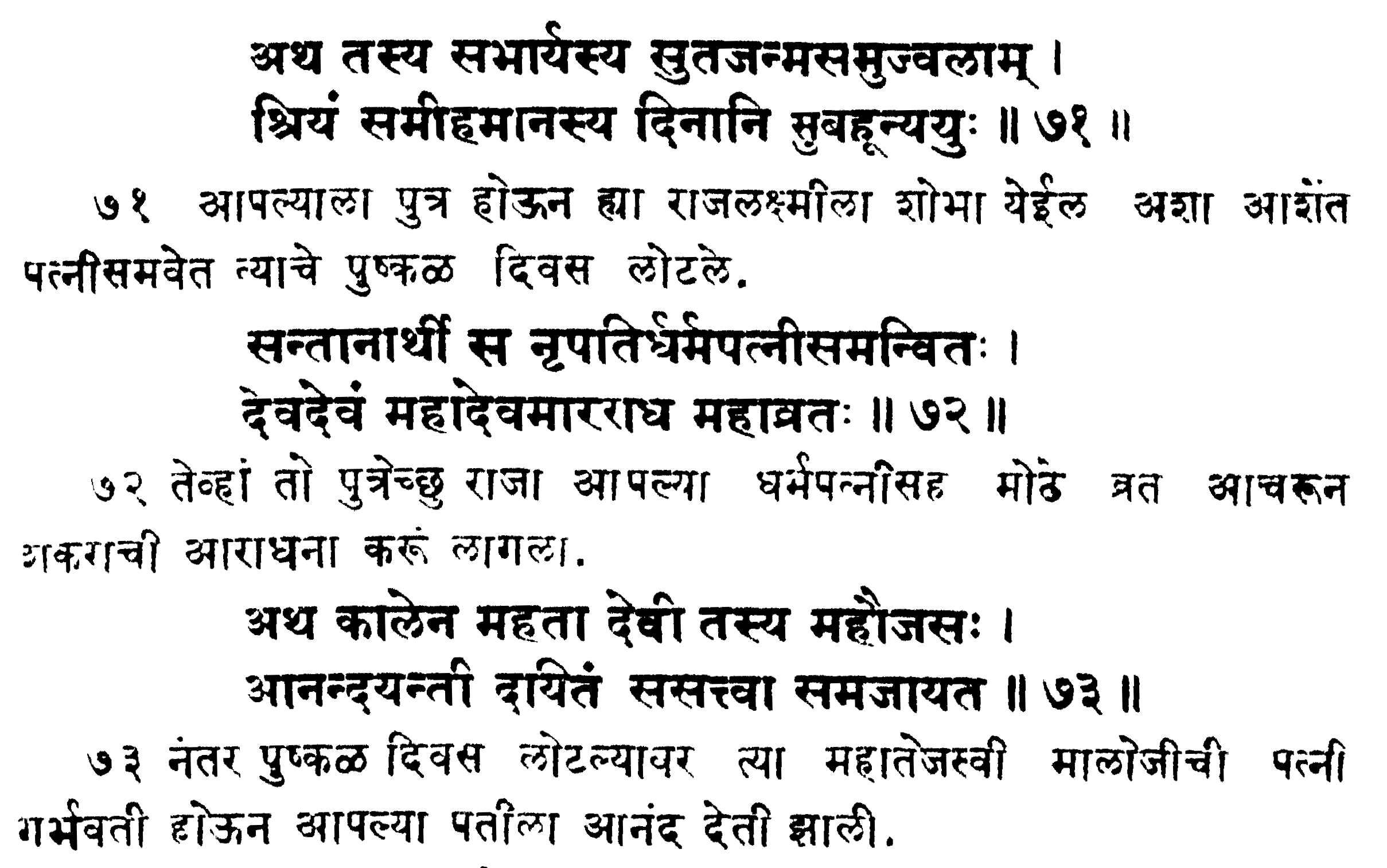

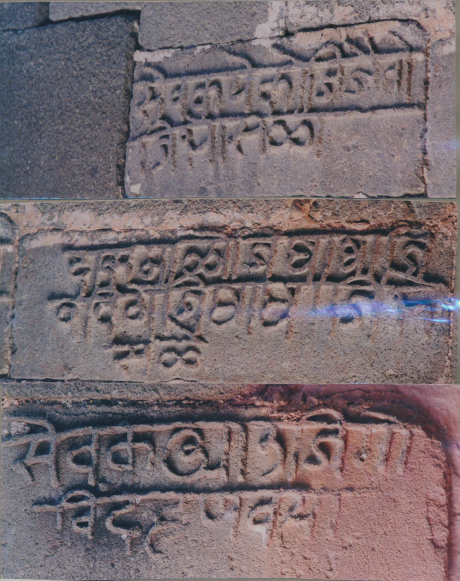

Further, there is no reference of a नवस (mannat or approaching a shrine or spiritual person for wish-fulfilment) by Umabai or Maloji before Shah Sharif in ‘Shivbharat’, which was the first officially commissioned biography of Chhatrapati Shivaji, in Sanskrit, by his court poet, Kavindra Paramanand Govind Newaskar of Poladpur, written on his instructions and during his lifetime. The following slokas in ‘Shivbharat’[6] (pics) cover the period of Shahji’s birth:

Days passed in the hope that his wife Rajlaxmi would be graced with the birth of a son (child). (71)

The Raja [Maloji] and his wife began practicing austerities (vrata) for supplicating Shankara to obtain a son. (72)

After many days had passed thus, the great Maloji’s wife was with child giving him immense joy. (73)

There is not the faintest reference in these lines of Maloji obtaining an offspring with the grace of a Muslim saint, in contrast, mention their practicing traditional Hindu pieties for fulfilling this desire.

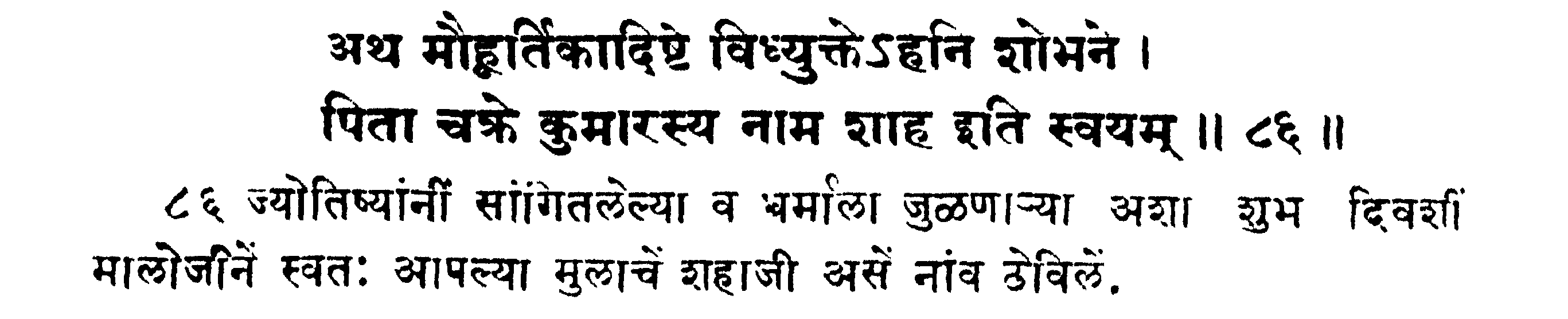

Describing the naming of the first child thus born ‘Shivbharat’ further gives us these details:

Maloji named his son Shahji on a sacred day determined by the Jyotisha and as per dharma. (86)

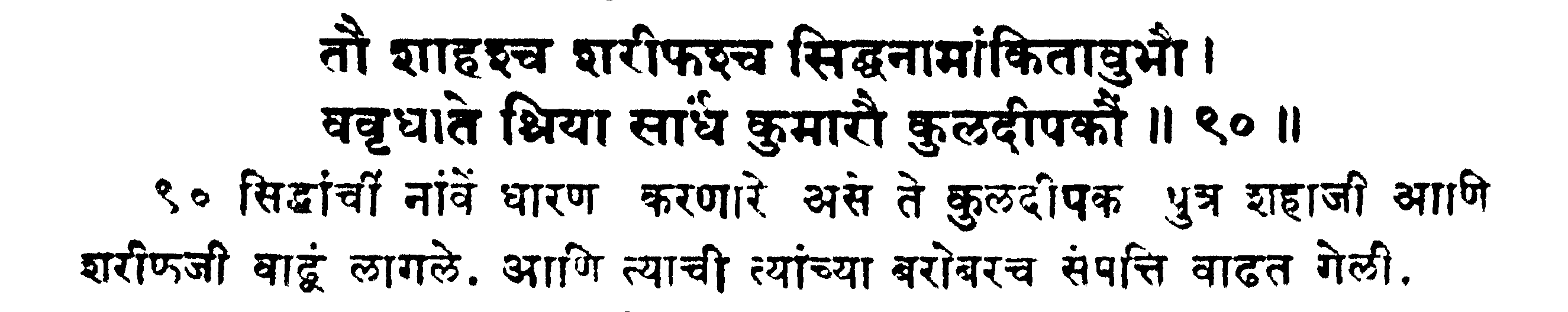

Regarding the names of Maloji’s sons the ‘Shivbharat’ narrates:

The Kuldipak sons Shahji and Sharifji bearing names of Siiddha began to grow and with them grew their wealth. (90)

The name of the siddha is not mentioned in ‘Shivbharat’. Since this book describes the Nizamshahi rule in a positive light, there appears no reason why the name of the Muslim saint would not be mentioned if indeed the children had been obtained through his blessings.

Historian Vishwanath Kashinath Rajwade who studied the life of Shahji further explains in a note written as introduction of the 17th Sanskrit book ‘Radha Madhavvilas’ by poet Jayram Pindye on Shahji:

“…Syyaji, Shyaji, Shahaji, Shahji, Sahaji, Sahji, and others are Urdu, Braj and further corruptions of Sinhaji (lion). The Original name should be Simha. One brother’s name is Simha and the other brother’s name is Sharab. Simhak and Sharbhak are two famous names found in Sanskrit literature… The names Shahji and Sarfoji being given due to navas of Shahsharif Fakir is later deception.”[7]

Rajwade expresses the opinion that the story of an association with Shah Sharif (if at all it originates in the time of Shahji) may have been made up for gaining acceptability in the Nizam Shahi court.

We come to know from contemporary documents that the area of 10 to 12 miles around Ahmednagar had been under the control of Mughals from 1602 CE. Maloji is known to have frequented the surrounding areas of Indapur and Verul, The story may have originated from this circumstance since from the physical proximity of these places to the saint’s abode it may be suggested. But there is absolutely no documentary evidence from which this is borne out.[8] No such reference can be found in any of the letters of Shahji or Shivaji.[9]

Another passage quoted by Deol from Pillai’s book reads: “His grandfather, Maloji, was not only a loyal officer of the Nizam Shahs of Ahmadnagar, but his samadhi is, evidently, ‘a completely Islamicate’ structure that still stands in Ellora. In the Sivabharathi, when praise is heaped on Maloji, it is in words that confirm his loyalty to his Muslim sovereign: ‘Whatever enemies did arise [to oppose] the Nizam Shah, mighty Maloji opposed them.Shivaji’s mother’s family too, similarly, had pledged affiliation to the Mughals years before and had no qualms serving a Muslim emperor. And to top it all, Shivaji himself, when he was in his twenties, had Muslim Pathans in his armies, also employing qazis to administer Islamic justice within his dominions.”

Maloji Raje and Jijabai’s family had indeed been in the service of the Nizam Shahi and the Mughals respectively. However “pledged affiliation” may be too strong a statement to make. Such associations were often made by Hindus as compromises for avoiding destructive war. Hindu nobles or chiefs who served under Muslim rulers were not known to be treacherous, since that is not the essential nature of the Hindu—and this characteristic of the Hindu is acknowledged in Mughal records—these were however not as a result of undying loyalty, but necessity. Hindu rulers acted independently as did Maloji Raje as well on various occasions. His devotion to Shiva is demonstrated in the fact that he undertook to reconstruct the ancient Grishneshvara[10] shrine in Verul (Ellora) which had been destroyed in the 13th–14th centuries during invasions of the Delhi Sultanate.[11] In fact, the rebuilding of the Grishneshvara shrine by Maloji may be seen as the earliest instance of reclamation and restoration works of Hindu edifices carried out by the Marathas. Noted historian G. S. Sardesai observes on Maloji:

“He soon managed to amass some wealth and enhance his reputation, so as to figure prominently in higher circles. He repaired the old dilapidated temple of Ghrishneshvara at Verul and built a large tank at the shrine of Shambhu Mahadev near Satara and thus reproved the scarcity of water at the place from which the large crowds of pilgrims had so severely suffered. Maloji was doubtless a man of resourceful and independent spirit.”[12]

The claim “…his [Maloji’s] samadhi is, evidently, ‘a completely Islamicate’ structure” has to be put down to an outright falsity. Quite a few of the samadhis of the Bhosales are located in Verul, one of which (shown in this video) is said to be that of Maloji Raje. As per another version, his samadhi is at Indapur where he died. This structure is in a dilapidated state. But none of the structures in Verul can be described remotely as “completely Islamicate”. Many of the structures of Hindu temples and monuments around Verul were modified to appear as Islamic structures during Mughal emperor Aurangzeb’s demolition sprees all over his realms. It is possible that some of the Bhosale memorial structures may have been compromised. But it would be evident even to a casual observer from the carved brackets all around the exterior walls, that the samadhis, which are all similarly designed, are not “Islamicate”, but in the likeness of cenotaphs of Hindu kings with canopy-shaped roofs fashioned as chhatris. They show far more a Rajput influence than Islamic.

A 17th century memorial at the apex of Shivneri fort, dedicated to Koli soldiers who sacrificed their lives in a fight with the Mughals, may be seen for comparison.

Similar square – domed – trimukhi pattern can be seen in Rajput chhatris, e.g. in a cenotaph in Mehrangarh fort, and an almost identical carved domed roof with crenelles in Bara-Khamba chhatri in Hindaun, Rajasthan. (pics)

The cenotaphs along the river Betwa in Orchha also show similar contours as the Verul structures and this appears to be a familiar pattern in the Madhya Pradesh-Maharashtra region.

Deol seems to find great resonance in the whitewashed account of Pillai quoting another one of his passages which says: “It was Shivaji’s immense drive to become a powerful presence in Deccan politics that pushed him to take such steps. He also believes this drive was accompanied by the ruler’s empathy for the poor who had been suffering for years in ‘endless wars due to the Mughal invasion, reducing the region to unprecedented desperation.’

The path that Shivaji had determined on was against the tide of the day. If he wished for dominion and power alone, he could have done so easily while serving under the Muslim rulers or changing allegiances to suit his aim. That he had no intention to take that recourse and instead set out very early in his life on an almost insurmountable course of maintaining his independence and not submitting to any of the Islamic rulers (except as stratagem) speak against this diminution of his aims. His campaigns against the Portuguese were undertaken purely for delivering the Hindus from their cruel persecution. He was of course exceedingly astute and not an idealistic fool in pursuing this aim, but his vision for a sovereign Hindu nation comes through clearly in his letter of 1665 CE to Mirza Raja Jai Singh, in which he tries to bring him around to his vision exhorting him to fight for Hindus and rid himself of ignoble vassalage of the Mughals.[13]

The aspect of Muslims in Maharaj Shivaji’s army and administration (or rather the lack thereof) will be discussed separately in an upcoming section of this article.

Cover Picture: ‘Vijay Durg’, one of the marine forts on the Sindhudurg coast, on the mouth of Vaghotan River in Ratnagiri, captured by Chhatrapati Shivaji from the Adil Shahi sultans in 1653 CE (Source: Pune 365)

[1] “To Sevagy, Generall of the Hendoo Forces…” (English Records on Shivaji, p. 109, Shiva Charitra Karyalay, Poona)

[2] ‘ Jwaljwalantejas Sambhajiraja’, by Dr. Sadashiv Shivade, pg. 388; ‘Chhatrapati Sambhaji Maharaj’, by Dr. Kamal Gokhale

[3] दावा द्रुमदंड पर , चित्ता मृगझुंड पर ।

भूषण बितुंड पर , जैसे मृगराज है ॥३॥

तेजतम अंस पर , कान्ह जिमि कंस पर ।

त्योंमिलेच्छ बंस पर , शर सिवराज है ॥४॥

“As a forest-fire is to the forest trees, a leopard to the deer-herds and a lion to the stately elephants; as the sun is to the darkness of night, as Krishna was to Kamsa, so was king Shivaji, a lion, towards the race of mlecchas.”

[4] ‘Shivaji: His Life and Times’, by Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale (He gives Shahji’s birth date according to his birth chart, published in ‘Bharat Kaumudi’ Part II, p. 755, and ASN Vol. IX, pg. 95)

[5] ‘Shahjiraje Bhosle Vyaktivedh’ pg. 29-30, in ‘Itihasachya Paulkhuna’ Part 2 (Marathi)

[6] ‘श्री शिवभारत – कवीन्द्र परमानन्द’ (Marathi translation of ‘Shri Shivbharat’) by Sadashiv Divekar – Adhyāy 1, pp. 10-12.

[7] ‘Radha Madhavvilas’ (Marathi), by V. K. Rajwade

[8] ‘Shahjiraje Bhosle Vyaktivedh’, pg. 31, in ‘Itihasachya Paulkhuna’ Part 2 (Marathi)

[9] Whether the names ‘Shahji’ and ‘Sharifji’ are of Sanskrit or Arabic origin cannot be ascertained either way with certainty, since the words occur in both languages.

[10] One of the 12 jyotirlingas as per Hindu Puranas

[11] ‘Shivaji The Founder Of Maratha Swaraj’, by C. V. Vaidya, pg. 15 (“The temple was destroyed again during the later Maratha-Mughal conflicts. The current temple was rebuilt under the patronage of Ahilya Devi Holkar.”)

[12] ‘New History of the Marathas’ Vol. 1, by G. S. Sardesai, pg. 52

[13] ‘शिवकालीन पत्र सार संग्रह’ खंड 1, क्रमांक 1042; ‘Shivaji Souvenir’, by G. S. Sardesai, pp. 161-163