By Smita Mukerji

Read the previous section of this series here.

The Cellular Jail, Port Blair – 1

Though the first Indian War of Independence of 1857 was quelled, the Indian freedom movement continued to grow in latter 19th Century leading to steadily increasing numbers of political prisoners. The colonial authorities seemed apprehensive of confining the nationalists in the mainland where they could spread their ‘dangerous ideas’. Further numbers were added from other unrests like those from the Wahabi Movement in 1865, the Manipuri Revolt in 1891[1], and a large number of Burmese from Tharawadda (1885-95), as Britain fought several wars to gain control of South-east Asia. Between 1858 and 1939, the British Government of India (GoI) had transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the settlement in the Andamans[2], which made it the largest penal colony in the entire British Empire. Initially convicts were kept in open enclosures after deportment to the colony. But with time this became unmanageable as authorities found it difficult to enforce strict discipline, and after hundreds of attempts by prisoners to escape by swimming across the ocean, a high security jail that could hold a large number of inmates became a necessity.

From its inception, the administrators of the settlement had vacillated between the aims of preserving the penal character of the Andamans and the policy of colonisation and development of the Island through the agency of an enlarged population of ex-convicts and their families with the self-supporter system. But for the British GoI the former always outweighed the latter. In a letter to the Superintendent of Port Blair[3], the Governor General in Council advised:

“The main and primary object for which the Settlement is maintained is to secure that the sentence passed upon convicts is properly carried out under a well regulated system of discipline, and to this object the profitable employment of the convicts and the development of the resources of the islands must be considered subordinate.”

The Andaman penal system developed sui generis, i.e. grew on its own lines adapting to the requirements of the situation, without definite rules for the management of convicts and independent of the Indian prison system. Successive superintendents of Port Blair were guided by general instructions issued from time to time by GoI. It was only ten years after the establishment of the settlement that rules of the Governor General in Council for the management of transported convicts were framed under Section 34 of Act V of 1871 (prisoners) on July 29, 1874.

From various experiments, curative actions and repeated failures over a century, it became increasingly apparent that the object of building a decent self-supporting community of ex-convicts was decidedly a failure. Ridden with both conceptual and administrative flaws and mismanagement, and an appallingly low ebb of morality among the displaced persons in the absence of traditional social, moral and religious checks and balances,[4] there was a wide dissonance between the ideal prospects of the penal settlement and the outcomes owing to impediments of practical implementation. Major H. N. Davies, deputed by the Chief Commissioner of Burma to inspect the settlement at Port Blair in May 1867, made a telling remark in his inspection note:

“…the self-supporting system at present in force is carried on under strict conservative rules, and was falling short of its objects. The present system is a failure more or less, and in such cases policy generally dictates a change.”

In January 1890, Surgeon-Major A. S. Lethbridge, Inspector General of Jails, Bengal, and C. J. Lyall of the Bengal Civil Services and Chief Commissioner of Central Provinces, visited the Andaman penal settlement, deputed by GoI to ascertain whether the regulations at the settlement were sufficiently stringent in character in securing the full deterrent effect of the sentences of transportation, and if not, in what way they could be made so. Their report submitted on April 26, 1890 concluded that the existing penal system in the Andamans did not have any deterrent effect on the convicts. The abolition of extra-mural labour and strict confinement of prisoners within jail walls in the Indian mainland made their sentence more severe and convicts preferred transportation to the island penal colony.

Though Lyall and Lethbridge were in favour of encouraging prisoners to settle in the Andamans instead of allowing them to return to India, they recommended increase in severity of confinement in the Andamans, classification of habitual and non-habitual offenders, gradual discontinuance of transport of term convicts, the segregation of female convicts, and other measures for enforcing discipline like confinement in isolation of convicts in cells in the preliminary stage for six months[5], followed by confinement in a limited area in the second stage of eighteen months in the jail barracks, where the prisoners in association with other convicts would work on intermural industries.

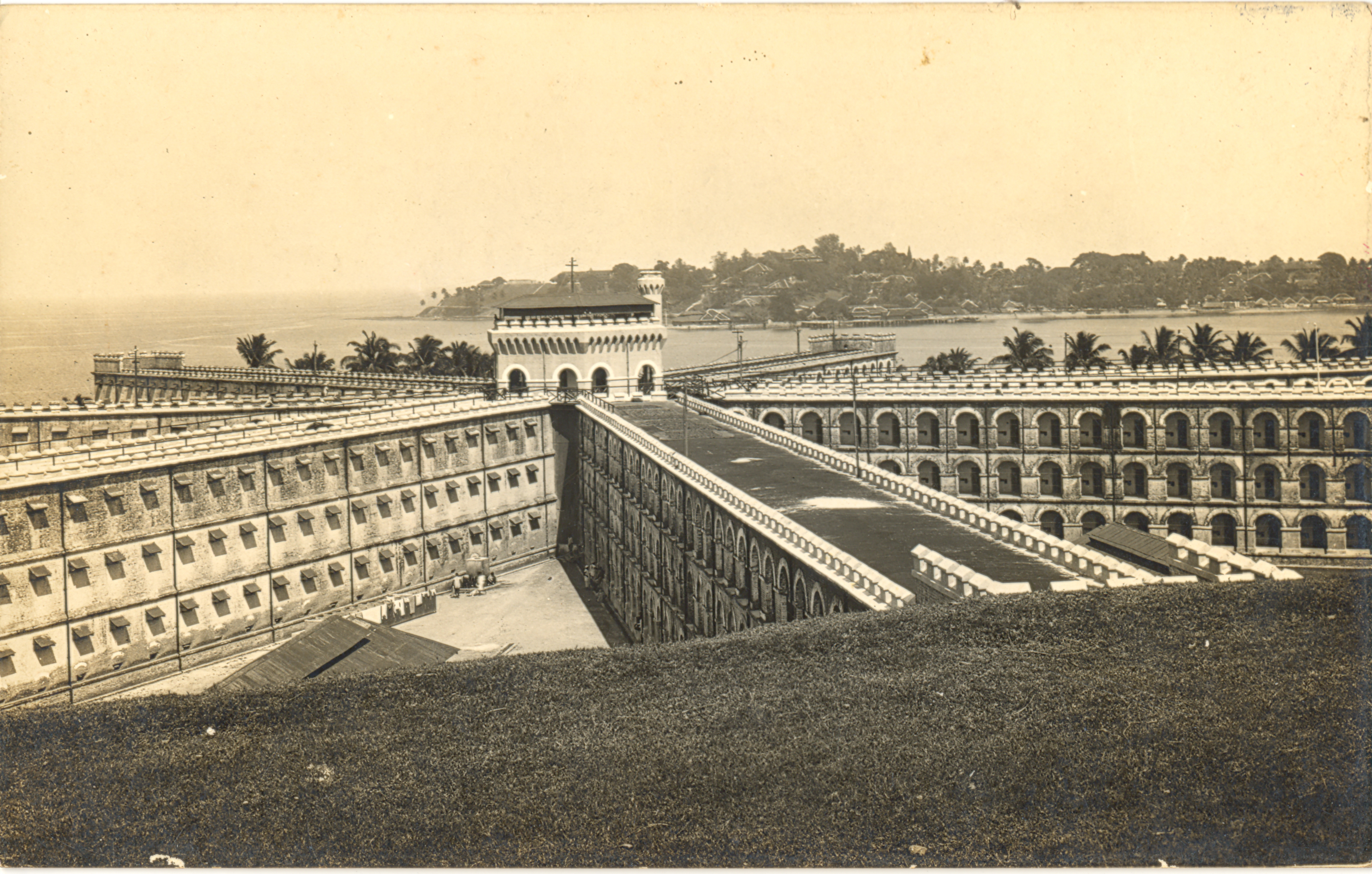

This entailed construction of a larger incarceration facility, the proposal for which was accepted and with the settlement order number 423 of September 13, 1893, construction of a new Jail building was begun in 1896 in Aberdeen[6] using the prisoners as ready construction labour. Made to slave to erect the stockade for their own internment, the convicts watched the jail complex come up around them, which was ready for occupation in 1905-06.[7] But even before the completion of the Cellular Jail (CJ) complex there were murmurs of doubts about the efficacy of penal transportation to the Andamans.

In a note submitted in 1904[8], W. R. H. Merk, the Superintendent of Port Blair from 1903, expressed the view that time had come when transportation to the Andamans should be stopped on account of the fact that the life of the prisoners in these islands, except for a short period in CJ, was much more free and unrestrained than that of a prisoner in an Indian Jail. The considerable government spending over the entire exercise of sending a convict to a penal settlement[9] which had lost its reformative value, was regarded by him as extravagant. This view had been echoed in the reports of numerous preceding inspections detailed by the government, as well as subsequent ones to assess whether continuance of the settlement in the state it existed was expedient. Proposals for its discontinuance however had to be repeatedly scuttled since the provincial governments expressed their inability in holding such a large number of prisoners in mainland prisons, as also the difficulties of the Andaman authorities on account of shortage of convicts for construction work in the Island. It was however a different category of convicts for which the Andaman penal colony came to be known historically.

While conceding that abolition of the colony was inevitable, GoI remained opposed to its complete discontinuance as a place of exile since maintaining the establishment at the Andamans for reception of convicts had obvious advantages, particularly for the deportation of habitual criminals and a class of selected prisoners termed ‘especially dangerous offenders’ whose removal from India was said to be ‘in the public interest’, a description applied to political prisoners.

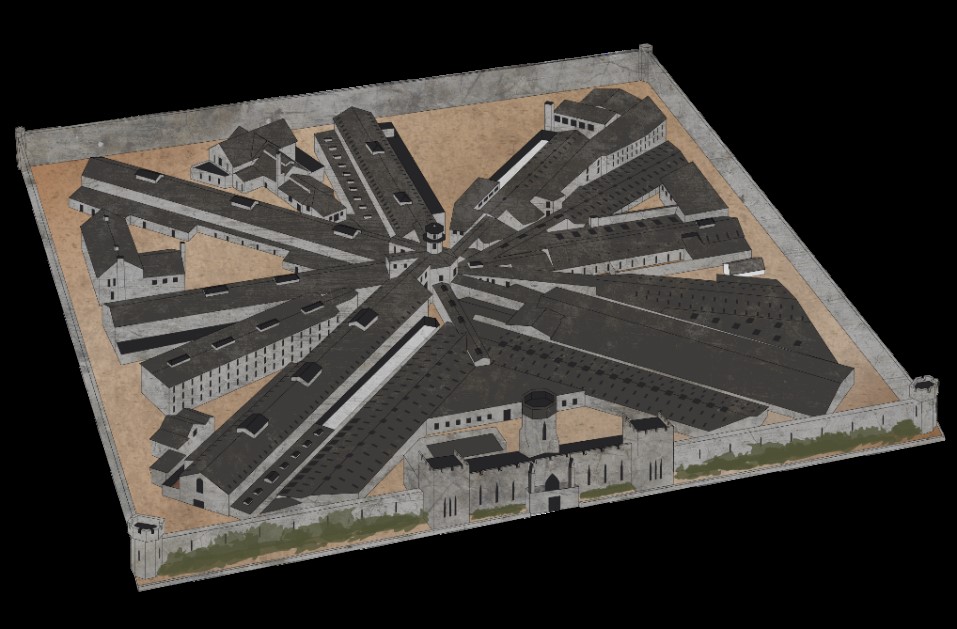

The concidence in the stories of Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) and the Cellular Jail (CJ) in faraway Port Blair in the Andaman Islands, is uncanny, that goes beyond the obvious similarity in architectural design. CJ has the same hub-and-spoke panopticon structure in a circular array as ESP, consisting of a central watch tower from which seven long three-storied wings shot out. The wings were of varying length, each of three storeys with rows of about twenty or thirty single iron-gated cells, 693 in all.[10] The blocks are connected by a staircase and drawable bridges at the central tower which has only one gate for egress and ingress that was well-guarded. The central tower had an additional storey to facilitate the function of watch and ward. A night watchman guarded each of the corridors in the night and a sentry from the central tower moved continually up and down the storeys asking each watchman about the situation. The doors of the cell would be locked at about 9 or 10 P.M. Just like ESP the exterior has the forbidding appearance of a castle, but the sheer scale of CJ makes it far more impressive.

Another feature that distinguishes the two structures is that the wings of CJ are built back to back and not facing each other, so that the face of each row of cells saw the rear of the one in front, making communication impossible. Each cell was 4.5 by 2.7 metres (14.8 ft × 8.9 ft) in size fitted with iron bars facing the verandah and a window on the opposite wall at a height of 3 metres (9.8 ft) for ventilation. The verandah was surrounded by iron railings fixed into the arched pillars supporting the roof ran all along the front. It was from this structural peculiarity meant for solitary confinement without any contact whatsoever with other prisoners that the jail derived its name, ‘Cellular Jail’. But the similarities end there.

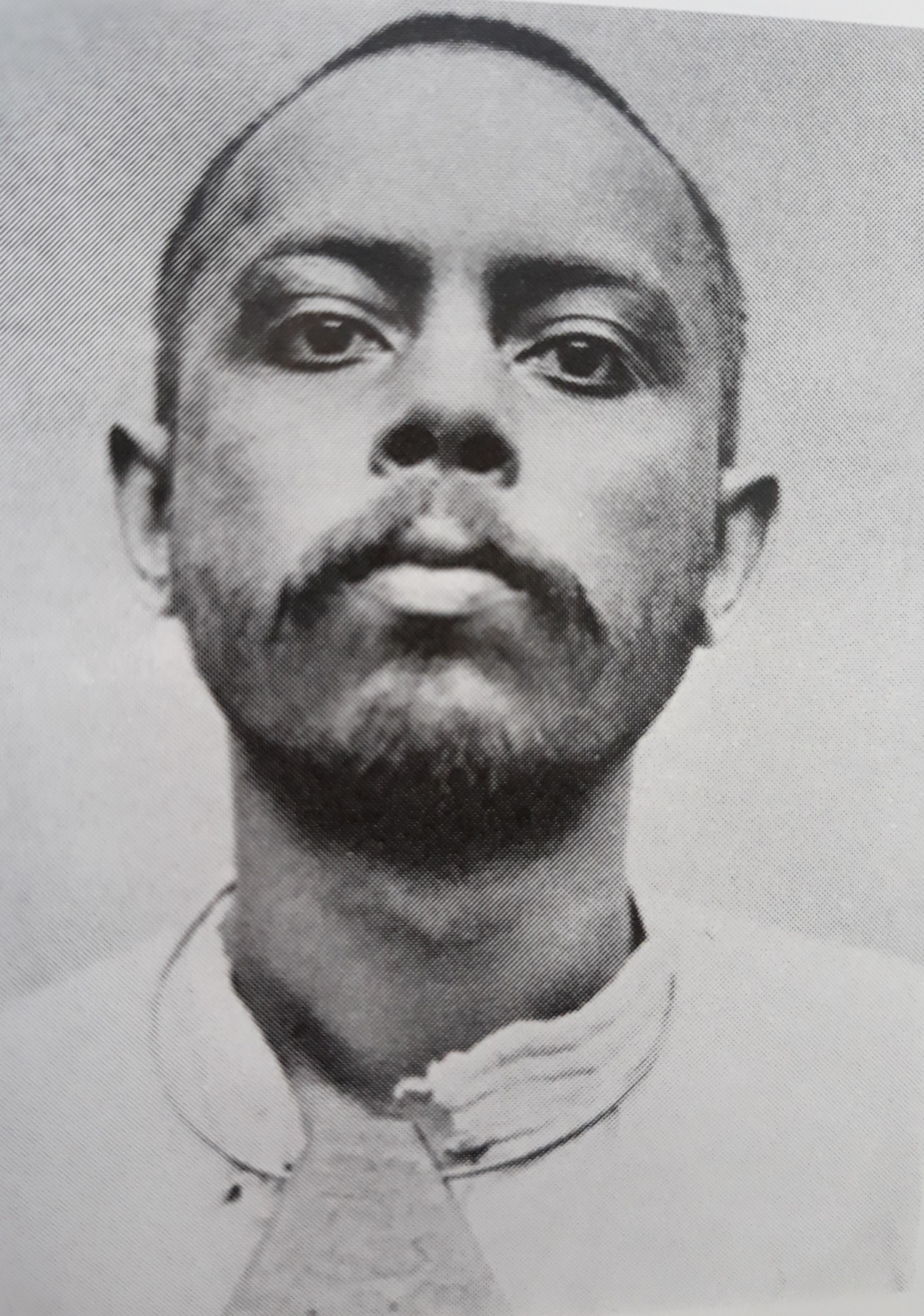

The CJ precincts too witnessed similar horrors meted out to its inmates, yet was quite different from ESP. The very founding ideas were diametrically opposite. In contrast to the benevolent, paternalistic outlook of a corrective home that ESP was based on –misplaced it may well have been– CJ was designed to break the spirit of its inmates, especially the political prisoners, who towards the latter period of the settlement constituted a major chunk of the inmates, to demoralise them[11] and defeat the Indian freedom struggle.[12] At CJ torture was not an irregularity reserved just for the contumacious, but formal policy laid down in its conception as part of the recommendations by Lyall and Lethbridge, that a “penal stage” should exist in the transportation sentence, whereby all prisoners would be subjected to a period of harsh treatment upon arrival. The inhuman conditions, the excruciating daily grind, the soul-destroying sadism of its keepers was devised calculatedly to snuff out the will to live in the prisoners, leave alone continue a political struggle. There were cases of inmates committing suicide and losing their mental balance even in CJ, but the ones who succumbed were not ailing psychologically, but because the incessant crushing of their minds and bodies on a daily basis with the rigours of the jail caused their will or their sanity to snap. One of the most notable freedom fighters who served time at CJ, Vinayak Damodar Savarkar[13], recounted in his biographical ‘My Transportation for Life’ the menacing words of the abominable custodian of CJ, jailor David Barrie, warning the newly arrived prisoners against making any attempt to escape. The notoriously cruel jailor took it upon himself as personal errand to suppress the enemies of Britain, who he would refer to as “a despicable lot, vagrant wretches and the scum of the society”, with a model of vile abuse and crude violence.

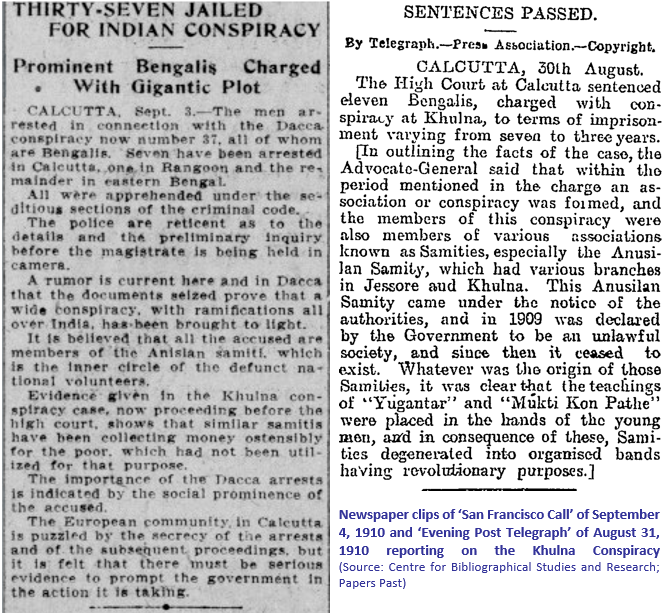

By the turn of the 19th century a vigorous revolutionary movement was building up in India inspiring love for the motherland and preaching the gospel of freedom. The revolutionaries propagated the idea of forceful, if required, violent overthrow of the British government, through numerous secret societies operating all over India, especially in Bengal. The British government responded with repressive measures and imprisoned several militant nationalists in jails. But they still could not check the ‘contamination’ of the ideas, as these spread from them to the fellow prisoners. The only way to prevent it was, isolation of the freedom fighters by removing them to the Andamans. The British remained initially hesitant to carry this out as differential treatment to those sentenced for political offences appeared impolitic[14]. This changed with the unearthing of the Maniktola conspiracy, famously known as the ‘Alipore Bomb Case’, seen as a grave case of ‘waging war against the Empire’, in which six of the undertrials received various sentences, including death sentence. The government accepted the proposal to transport them to the Andamans, the cited reason for which was the same as that for the 1857 ‘Mutiny’, i.e., it was important to remove this class of criminals from India.[15] Following this, independence activists from several provinces were transported to the convict settlement, notably those convicted in the Khulna Conspiracy, the Barisal Conspiracy, and the Nasik Conspiracy Case. The Government of India was determined that political prisoners’ labour should remain strictly punitive[16], supposed to perform only rigorous manual labour regardless of the length of stay in the islands[17], however not in the same gang with each other nor prisoners from other provinces with Bengali convicts, as Bengali ‘terrorist prisoners’ were considered especially dangerous.[18]

The cells at CJ were equipped with none of the conveniences and comforts of ESP. The only furniture in the room was a low bedstead, one cubic and a half wide. They had no toilets and inmates were provided with just two clay bowls, one for water and another one painted with tar placed in a corner of the cell for the inmates to relieve themselves in. The pot was so small that it was difficult to use and as the sweeper cleaned it only once in the morning, they were compelled to tolerate the foul stench through the night. Some prisoners became so desperate that they resorted to using the bare floor. Many times the prisoners were not allowed to clean it in a day and forced to “sleep with their heads near the nuisance [they] had committed,” in the words of Savarkar. Constructed with inferior material, the walls of the cells were damp with seepage and infested with insects and scorpions. There were no lights and in the absence of proper treatment many inmates died due to the fever from scorpion stings.

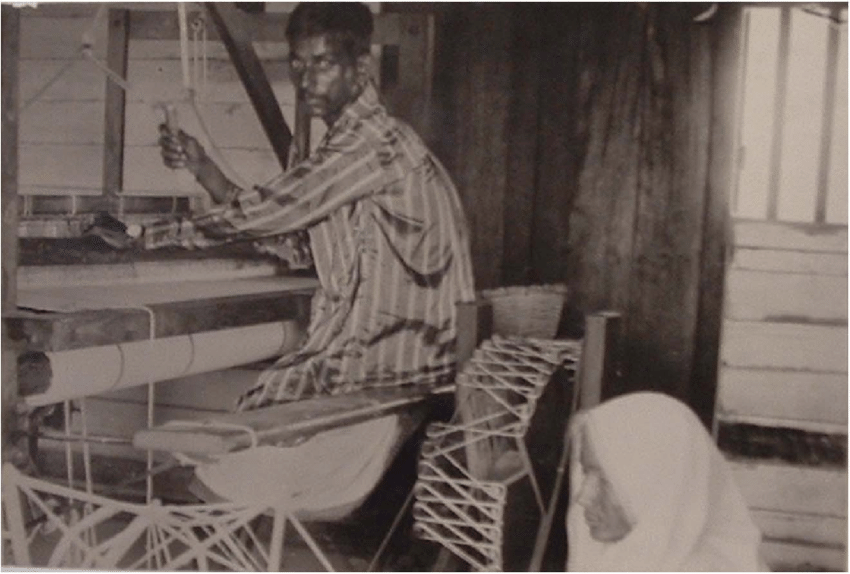

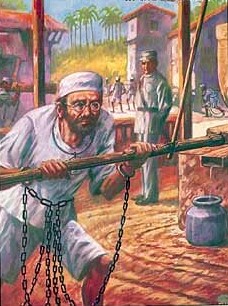

Treated as lowly criminals, their movements hampered by crossbar fetters, neck ring shackle and leg iron chains, the freedom fighters were put through unendurably hard toil like cutting hills and swamp-filling, beating coconut husk with incessant blows of a heavy hammer to produce over three pounds of fibre each day. Barindra Kumar Ghose[19], who spent more than 10 years in the jail, described those who were given coconut or coir-pounding as living “in a state of suspense, as it were, between life and death.” They would be yoked in place of bulls at the oil mill to manually turn the wheel, connected to a device that pressed oilseeds/coconuts in a pestle to extract oil, and had to drop by drop produce a backbreaking daily quota of 30 pounds of oil. Many would collapse out of exhaustion since this amount could not be produced even by a bull. Satadru Sen notes:

“…it is clear that the labour to which political prisoners were subjected in the Andamans was intended to function as a form of torture… There was, in such labor, no question of ‘reform,’ and no possibility of rehabilitation. Political prisoners were not expected to actually meet their quota of oil; those who did were not rewarded…”

No matter how fatigued they were they were allowed no rest, and any sign of slowing, as much as asking for a cup of water, invited the overseer’s wrath in the form of a torrent of lashes and abuses.[20] The Jailor did not accept the advice of the doctor to send prisoners who were ill to the hospitals and forced the sick prisoners to work.[21] The political prisoners belonged to the intelligentsia and had never done manual work. Even after relentless daylong labour which sometimes caused their hands to bleed, if they failed to accomplish the physically impossible quantum of work they were alloted, sinister punishments were handed them to them, like being kept on invalid diets and penal clothing[22], and corporal punishment, being whipped or flogged tied to a tripod stand, or tied to an iron frame constrained in standing position over days and banished to the lonely lock-up of their cells to languish in shackles.

Savarkar observed that by giving preferential treatment to Muslim inmates and setting Muslim (from Sindh, Baluchistan and North-West Frontier Province) wardens on them the Hindu inmates were often compelled to convert.[23] As a deliberate ploy Muslim convict jamadars were tasked to supervise the political prisoners’ work who heaped numerous indignities upon them and brutally beat them up[24]. They would exact their daily share of food from the political prisoners and at refusal inflict torture in several ways.

“Even the jamadar dared pour foul abuse upon us and Mr. David Barry had instigated him to do so. The jamadar and his lieutenant slapped us on the face if we were found taking or had not finished our day’s work. And if we happened to report the incident to the jailor, the latter would laugh outright on his face.”[25]

The food they were given was unfit for human consumption: bread or gruel with worms and stones, boiled inedible wild grass in lieu of vegetables[26], and rain water full of insects and worms for drinking of which no more than two cups a day was allowed. They were not allowed to bathe except drenching themselves in rain and often they would not be allowed to wash their hands before eating. The political prisoners were not allowed to pass urine and stools at their own will, but only at three fixed times in a day. In case of need they would have to hold it for hours until they were permitted by the guards.[27]

There were sheds for the eating mess, with that for the gallows facing it, and the workshed. The gallows had nooses hung from a beam in the roof with a trapdoor beneath each noose, which would give way as soon as the noose tightened around the neck of a condemned freedom fighter, who would then hang painfully to death. Though enclosed, the cries of the unfortunate in their death throes could be heard across in the mess and it was apparently with design so, in order to terrorise and psychologically weaken their resolve. The body of the dead would then be released into the pit under the trapdoor connected to the sea by a passage. The journey along this cold, dark, wet passageway was the only last rites that a martyr would receive.

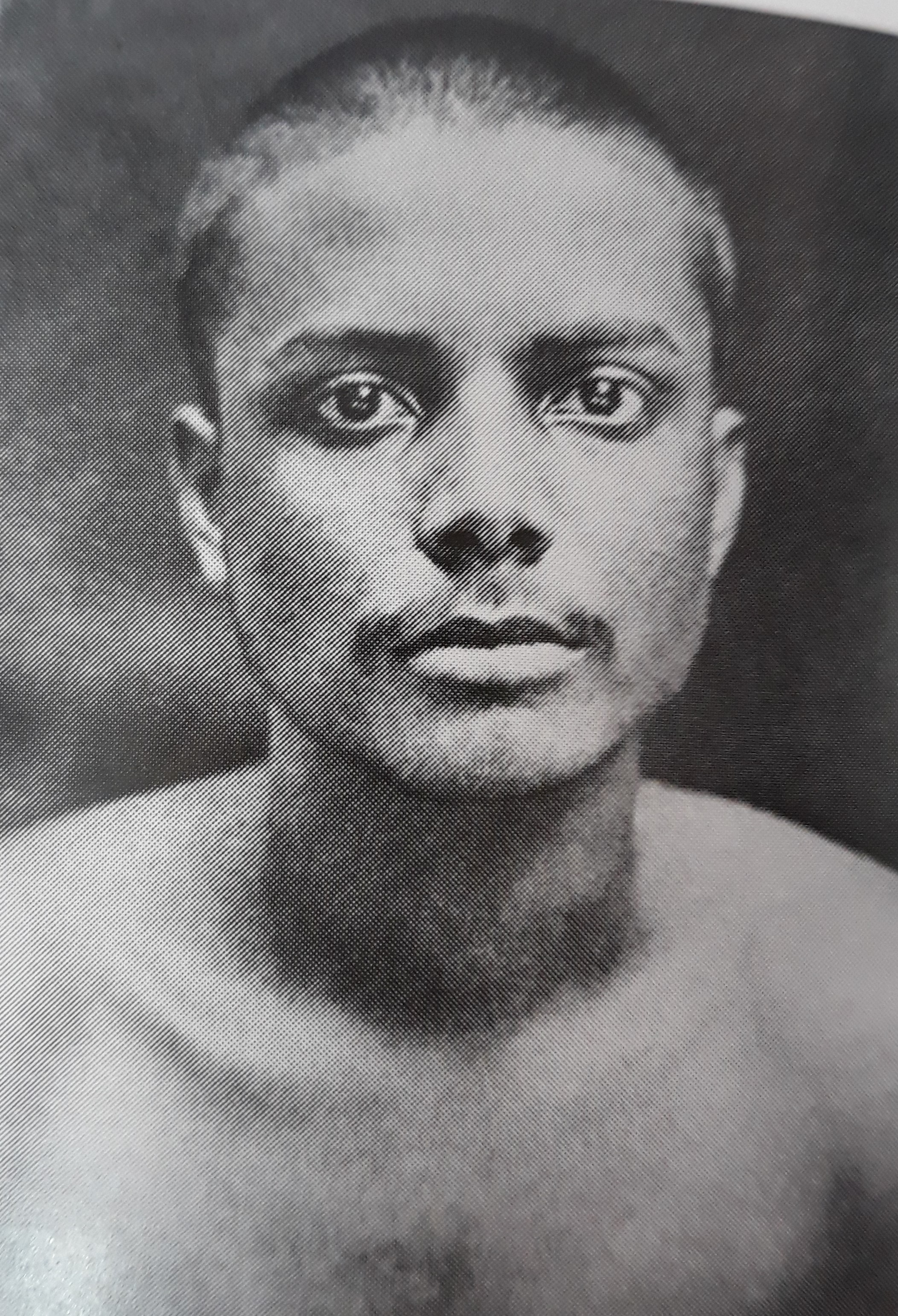

The revolutionaries were not accorded basic privileges due to political prisoners by the standards of civilised countries at that time. They were not assigned to clerical work for which they were qualified. Placed lowest in the prison hierarchy, the treatment accorded to them was worse than that to the basest of criminals. The right of earning remission was denied to them and they could never hope to become self-supporters. For some drawing breath itself became unbearable. One of the prisoners, Indu Bhushan Roy[28], committed suicide in April 29, 1912, found hanging from the iron vent at the back of his cell, with a noose around his neck made from his own torn clothes “exhausted by the unrelenting oil mill.”[29]

Soon thereafter, Ullaskar Dutt[30] turned insane. Punished for refusal to work as a construction labourer, three days into the hands-up fettered position, Dutt was released, unconscious and found to have lost his mind.[31] “I lay on my bed, my eyes riveted on the barred window,” Savarkar scratched on his cell wall, “down the corridor, ‘troublemaker’ Ullaskar Dutt was hanging by his wrists from a peg hammered into the wall above his head, one day into a seven-day punishment for accusing Dr. Barker of aiding Roy’s death.” Savarkar was the first to hear his cries on June 10, 1912 as warders dragged him down the Yard Five Wing. Dr. Barker, waiting at the jail hospital, used a device to check if the prisoner was acting up. “I could feel the metal clips and then his battery playing on my body. The electric current passed through me with the force of lightning,” Ullaskar would recall many years later. He was transferred to the island’s lunatic ward at Haddo and in 1913 to an asylum in Madras. He would be held there for 14 years.[32]

Meanwhile, news of the custodial torture and deaths in CJ reached the mainland which aroused great indignance against the British government and stimulated a campaign for the better treatment and repatriation of these prisoners to India. A section of the Indian press took up their cause. On May 3, 1912 an article appeared in the ‘Bengalee’, edited by Surendra Nath Banerjee, based on a letter which one of the prisoners, Hotilal Varma, who had been the editor of the newspaper ‘Swaraj’, had managed to smuggle out of jail. The daily ‘Tribune’ of Lahore reproduced Banerjee’s article of May 3, 1912 levelling strident allegations of unduly severe treatment of the political prisoners. However these seem to have failed in evoking any sentiment of compunction in the Home Department, brushed off by the Home Secretary to GoI, Sir Reginald Craddock with the words that the “conspirators could hardly expect to escape hard labour in the Andamans”, and that “there was no cause for reasonable complaint by the political prisoners”. He regarded the behaviour of the officials of Port Blair towards the terrorists as “just and kind”.

Driven beyond what flesh and blood could stand, the political prisoners went on a hunger strike. Ladha Ram[33] was the first to refuse food on September 7, 1912, followed by Noni Gopal Mukherjee[34] on September 25 who remained on hunger strike for 72 days.[35] From the third day of their hunger strike both were forcibly fed twice a day by an oesophageal tube passing through their nose or mouth. Other political prisoners also joined the strike refusing to work. The Superintendent, Port Blair attempted to talk to them promising redressal and asked them to resume work. Some of them took his suggestion but the majority remained obdurate followed by numerous measures of coercion and threat used by the jail authorities to make the political prisoners buckle. They were punished with handcuffs, chains, cross-bar fetters, ‘gunny’ clothing, invalid diet and extension of their sentences. They were placed in solitary lock-up separated from each other by several cells preventing them from talking to each other and some of them were moved to the jail in Viper Island jail meant for hardened criminals.

Another article appeared in the ‘Bengalee’ on September 4, 1912, flaying the government for maltreatment of the freedom fighters incarcerated in Port Blair. This was followed by the issues of September 8 and 20, 1912 that charged the British Government for adopting an unduly harsh attitude towards the nationalist activists, neither according them the status of political prisoners nor granting them the privileges given to ordinary criminal convicts in the Andamans. The agitation in the press had by this time begun to perturb the British authorities.

As the hunger strike stretched on till December, GoI deputed Sir Percy Lukas, Director of Indian Medical Service to hear their grievances and make an attempt to institute a conciliation between the jail authorities and the strikers. As a result of talks with him some of the travails of the freedom fighters were remedied and they were allowed to leave the CJ premises, given lighter, more congenial forms of labour and given access to some books.[36] They in turn – according to the version of GoI – undertook to give no further trouble to the authorities. The permission to leave the premises was however revoked within just a few months alleging conspiracy of a violent attack by the ‘seditionist prisoners’ against the authorities. This was largely prompted by fear since it was observed that the political prisoners evoked sympathy among the self-supporters and prisoners in different gangs which could potentially provoke hundreds of prisoners to rise up against prison authorities. A dispatch of the home department noted to this effect:

“The Frontier fanatics may be expected to lay murderous hands on individuals, but the anarchists might not only compass their own escape, but might succeed in organising an outbreak or mutiny among the convicts. Once they are outside the walls of the Cellular Jail, they can count on the help and sympathy of numerous agents both among the convicts and among the free populace of the Andamans. Some of them are of a specially dangerous type, because they… have shown certain qualifications for leadership. Those who are followers only are not likely, unassisted, to cause much mischief individually, yet in association with the principle men they are capable of doing a great deal of harm.”[37]

Among them was V. D. Savarkar for whom was reserved the most extraordinary asperity. Condemned to more than 50 years of rigorous imprisonment, from the point of his arrival in the colony on July 11, 1911, the Superintendent, Port Blair was directed to place him under close watch.[38]

There was mounting pressure following the hunger strike on the Government to make the system of prison management more transparent. In a speech on February 24, 1914 in the Council of the Governor General of India, Surendra Nath Banerjee demanded that non-officials be allowed to inspect the settlement. Vijay Raghavachari[39] wanted a commission to be appointed to investigate the whole system of prison administration in India including the penal system in the Andamans. A resolution moved subsequently by Rama Rayaninagar[40] was accepted by GoI, that a jail commission of officials and non-officials be nominated to investigate the whole system of jail administration. This led to the appointment of the Indian Jail Committee which became a momentous event in the history of the penal settlement.

Cover image:

Cellular Jail, Port Blair Andaman Islands (Source: aldstudioblog)

[1] These prisoners belonged to the royal family and were interned in a bungalow on Mount Harriet, the only instance of prisoners condemned for ‘waging war against the King’ treated differently from the common criminals. “Many years later, however, when some of the well-known political prisoners were to demand similar treatment, the government of India was to comment that there was a difference between the Manipuri prisoners and those who were described by the government as secessionists, because the former Maharaja had no trial.” (M. Iqbal Singh, ‘The Andaman Story’)

[2] Clare Anderson, ‘The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire’

[3] N.A.I. (Home Department, Port Blair Branch, A Progs. No. 1, February, 1873)

[4] The greatest drawback of the system was that lack of thoroughly competent and trustworthy officers supported with an adequate establishment made it impossible to exercise an effective supervision over thousands of convicts scattered over different places for work. This led to heavy reliance on convict petty officers for watching over the convicts, and consequently the aim of every convict became gaining the favour of his petty officer rather than reforming himself. Even if a convict was motivated towards self-improvement and persisted in performance of his task, but did not bribe or ingratiate with his petty officer, he eventually found himself in the chain-gang for some offence which he had never committed, since it was in the power of the convict officer to report against those whom he disliked and to connive at breaches of rules in cases of favourites. Thus the only incentives before the convicts were those which tended to debase him.

As Craddock observed, “Bribery or intimidation and sometimes readiness to submit to unnatural connection may afford the royal road to privileges and indulgences according to the character of the convict or the petty officer concerned.” Every malaise of human character and every nature of vice predominated in the convict community, from substance abuse to violence, prostitution, rapes and ‘unnatural vices’ forced on hapless recipients, exacerbated by the chronic shortage of females in the settlement. In fact the settlement of Port Blair was a colony of the slaves controlled by slave petty subordinates and had no chance to succeed as a reforming agency.

[5] This stage of separate confinement in cells was to be tried only with habituals or ‘specially selected prisoners who had been sentenced for very serious crimes’. The latter definition encompassed the freedom fighters.

[6] A place in Port Blair settlement

[7] The construction of an associated jail as suggested by Lyall and Lethbridge, for confining a large number of prisoners in a restricted area for eighteen months after the initial confinement of six months in the Cellular Jail, was taken up later due to the paucity of labouring convicts and its construction was completed in 1916. In the intervening decade it was decided to locate habitual and dangerous criminals separately on Viper and Chatham islands for the specified period.

[8] N.A.I. Home Department, Port Blair Branch, A Progs No. 28-40, July, 1906

[9] The average expenditure on a convict in the Andamans at that time was Rs. 85 and annas ten. This was much less than the expense in 1867 which was Rs. 300 per annum per convict. (N.A.I., Home Department, Public Branch, A Progs. No. 89, December, 1867) But it was pointed out in comparison that only Rs. 43 and annas fifteen were spent on a prisoner confined in a mainland Indian jail. This amounted to an excess expenditure of R. 4,38,761 per annum spent on 10,525 convicts in the Andamans. (N.A.I., Home Department, Port Blair Branch, A Progs. No. 42, May, 1899)

[10] The number at completion. Later some cells seem to have been added making the total number 698.

[11] At the beginning of this chapter, Savarkar notes that life for the political prisoners before him had been difficult, but not unbearable. However, a few months into the imprisonment of the first group – from the Bengali Bomb Case – a “high official from Calcutta” (who remains mysteriously nameless) visited the jail and was extremely disappointed by the way the “Bomb-Makers” were being treated. As Savarkar tells it, this man proclaimed that political prisoners “…are the worst prisoners in the world and they must be treated in this prison in a way that will break their spirit and completely demoralize them.” (‘My Transportation for Life’)

[12] “The nationalist convicts were, for the most part, seen by the jailors as beyond rehabilitation, and as impervious to the mechanisms that were typically used in the Andamans to generate and sustain loyalty. As such, with these prisoners, the goals of transportation were isolation and containment, rather than reform and reclamation.” (Satadru Sen, ‘Disciplining Punishment: Colonialism and Convict Society in the Andaman Islands’)

[13] Leader of the revolutionary movement in Maharashtra along with his brother Ganesh Damodar Savarkar, Vinayak Damodar was a graduate of the Bombay University and had studied in London on a Scholarship given by Shyamji Krishna Verma. He came to be the acknowledged leader of the revolutionary group at India House. Arrested in what became known as the ‘Nasik Conspiracy Case’ he was sentenced to transportation for life, on the charge of ‘waging war against the King’.

[14] This was all the more since GoI had in 1906 suspended deportation of term prisoners to the Andamans.

[15] In a letter to GoI, the Government of Bengal referred to the observations of the judge, that it was desirable to prevent all these prisoners from mixing with the prisoners in other jails in India because of the possibilities of their inflaming the mind of ordinary criminals with revolutionary doctrine. (N.A.I., Home Department, Political Branch, A Progs. No. 84-87, December, 1909)

[16] (N.A.I., Home Department, Political Branch, B Proceedings, No. 1, October. 1910)

[17] In 1912 the Chief Commissioner in Port Blair wrote to reassure the government that such prisoners had ‘not been employed as writers or clerks’, and been restricted to ordinary jail labour. (GOI Home, Political Branch, December 1912, Nos. 11-31B; and February 1914, Nos. 68-160A)

[18] R. C. Majumdar, ‘The Penal Settlement in the Andamans’

[19] Arrested along with his brother, Aurobindo, and 39 others in the Alipore Bomb case, sentenced for life.

[20] Barin Ghose described them as ‘perfect adepts…in the art of beating and abusing.’

[21] They were invariably told that they were feigning illness in order to shirk work. In many cases the jailor did not accept the advice of the medical officer either to send the prisoner, to the hospital for treatment or to give him light work. Abinash, a political prisoner suspected of having contracted tuberculosis, was sent to the oil mill without even being examined.

[22] Dress made of coarse jute sack that was abrasive and irritated the skin.

[23] “I was sent to the Andamans in 1911, and I soon found out that some Hindu prisoners had been converted to Islam and assumed Muslim names after their transportation.”

“How strange it is then,” he questioned, “that… the Pathan and other Mussulman warders, petty officers and jamadars of that prison could convert the Hindu prisoners to Islam, by methods of conversion and coercion. Leave alone the prisoners who knew by their age what they were doing. But what of lads of tender age who were so forcibly converted to Islam by their Muslim warders? Is it not the duty of the British officers to care for their spiritual welfare as it is their care to look after their physical and moral well-being?”

[24] He notes that all the warders of political prisoners were Muslim because, “We were Hindus and a Hindu warder may be kind towards us. Hence the authorities put upon us Mussalman warders who reported our movements to them in an exaggerated form, or invented stories about us…”

“…the Pathans, as a rule, were bigoted Mohamedans, and were especially notorious for their fanatical hatred of the Hindus. The Officers had pampered them to serve their own ends. To persecute the Hindus was natural to them… The Pathans, the Sindhis and the Baluchi Muslims, with a few exceptions, were, one and all, cruel and unscrupulous persons, and were full of fanatical hatred for the Hindus. Not so the Mussalmans from the Punjab, and less even than they, those of Bengal, Tamil province and Maharashtra. But the fanatical section always belittled and held up to laughter their co-religionists from other parts of India. It twitted them as “half kafirs.” Savarkar mentions one ‘Mirza Khan’ who according to him was a “miniature Barry”.

This circumstance is corroborated by Upendranath Bandopadhyay (R. C. Majumdar: ‘Penal Settlement in Andamans’, pgs. 145-46) as also by Barin Ghosh in his biographical account ‘The Tale of My Exile’, in which he describes a petty officer ‘Khoyedad’, who was put in charge of the ‘bomb prisoners’ (as Ghosh and his companions were called), as “a Pathan, by race… There was an apprehension that Hindu guards might sympathise and fraternize with us. Therefore all the masters of our fate… where chosen from among the Mahomedans.” He described the Pathans as “Lazy and slothful and corrupt themselves, they are violently overzealous in extracting work from other people.”

In contrast, Hindu convict officers tended to be sympathetic to the political prisoners. Upendranath Bannerjee spoke of secret acts of kindness towards him by a convict officer who Savarkar specifies was a Hindu.

[25] This form of abuse directed at the political prisoners by warders from criminal classes much lower in social stature, education and intellect than them appears to have been deliberately encouraged to humiliate them. Savarkar narrates that if a convict officer made the mistake of addressing a political prisoner as ‘babu’ (common address for a lettered man among Indians) he would be reprimanded by the infamous senior jailor, D. Barrie, “What babu, who is babu here? They are all prisoners”.

[26] “One could somehow tolerate the coarse rice of Rangoon and the thick and tough rotis, but the preparations of kachri and unskinned green plantation and all sorts of roots, stalks and leaves boiled together with gravel and excretions of mice were intolerable.” (Barindra Kumar Ghose)

[27] Barin Ghosh narrates the case of a prisoner Bakula who “..was late in coming from the latrine”, at which Barrie ordered the wardens to “apply the baton and unloose the skin of his posterior.” Answering the call of nature also required the jailor’s permission who would growl fiendishly, “why the devil did you have it?”

[28] A young activist from Bengal who along with Narendra Goswami (who later turned approver in the Alipore Bomb Case) was said to have previously hurled a bomb at the mayor of Chandannagar and was convicted under the Arms Act of the Government of India.

[29] Contemporary report in ‘Amrita Bazar Patrika”

[30] A ‘Jugantar’ party member, sentenced for life in the Alipore Bomb Case.

[31] It was later found that he had been suffering from fever with a temperature of 107˚F. Savarkar wrote that Ullaskar had been certified as unfit for hard labour by the Junior Medical Officer (a Bengali), however his assessment overruled and by his European superior, following which the prisoner had been sent out to make bricks in the hot sun.

[32] News soon reached India and a series of despairing letters from his father, Dvijidas Dutt, to “His Excellency the Viceroy”, recovered from the Police archive in Calcutta, elicited but one brief reply from Lt Col H. A. Browning, chief commissioner of the Andaman Islands stating that “Patient’s insanity is due to malarial infection. His present condition is fair.”

[33] Editor of ‘Swaraj’ a nationalist weekly, he was transported to the Andamans merely for doing propaganda against the British rule in India. He was not accused of any terrorist activities.

[34] Sentenced to transportation for life for fourteen years in the Dalhousie Square Bomb Case, he was one of the most troublesome convicts for the authorities. He went on hunger strike on 14 different occasions and refused to work several times. He was never released from Cellular Jail.

[35] He again undertook a fast following Lukas’s visit since, though a young 18-year old and a term prisoner, he was put on hard labour in the oil mill. He was punished with disproportionate severity and against prison rules subjected to cruelty in spite of his young age at his acts of defiance demanding the status of a political prisoner. He refused to end his fast until Savarkar himself threatened to undertake a fast in order to pressurise Barrie to take him to Noni’s cell and personally dissuaded the young lad from continuing the fast. “Do not die like a woman. If you must need die, die fighting like a hero. Kill your enemy and then take leave of this world”, he told Noni, who finally ended his fast on October 5, 1913.

[36] These concessions were however not allowed to Savarkar and other prisoners transported for life.

[37] N.A.I. (Home Department, Political Branch, February 1915, Nos. 68-160)

[38] N.A.I. (Home Department, Political Branch, A Progs. No. 68-160, February 1915) “If he is allowed outside the Cellular Jail in the Andamans he would certainly escape. His friends could easily charter a steamer to one of the islands and a little money distributed locally would do the rest. In case he is sent to an Indian Jail he would certainly manage his escape from there also.” (Craddock) It is apparent that the daring attempt by Savarkar to escape from the vessel which carried him from London to Bombay was haunting the minds of the authorities.

[39] A prominent leader of South India, he was an Engineer and later became the Prime Minister of Mysore. He is remembered as the maker of modern Mysore.

[40] Member of Legislative Council of 1914 (Minister, Local and Municipal Department, Government of Madras)

good one .Liked it thank you so much for a brief and crispy information.

Thank you so much! Do read all the previous parts in this series.