By Smita Mukerji

Introduction

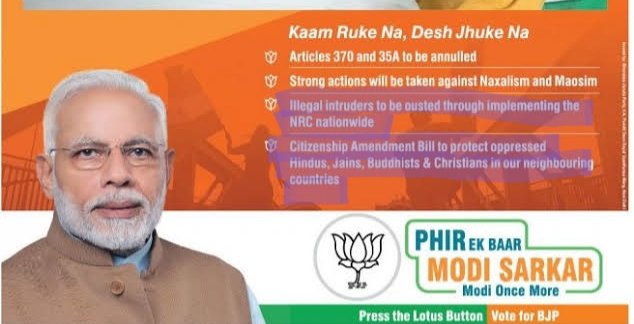

Ever since the PM Narendra Modi led Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was voted to power in the general elections in India in 2014, the discourse across the political spectrum has become increasingly polarised. A war of narrative is raging at present in India—as arguably in many countries around the world today—a perceptible trend of reviving nativist or nationalistic movements contending with the politically-liberal idea of indiscriminate globalism. It is in this light that the recent ‘protests’ against the newly enacted Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) must be seen. Precisely in relation to this enactment, however, it is important to bear in mind that India is in a unique situation, given its historical and civilisational background vis-à-vis its status as a modern nation state, which makes it difficult to understand its political dynamics strictly in terms of these two polarities.

Universities as focal points of party politics

The merits of student activism and campus politics has been long debated with opinions expressed both for and against it. Student union elections have been banned for extended periods in several states of India (e.g. Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha)[1], and after gaps allowed again in many of them subsequently. As a source of educated, aware young blood for recruiting cadres and incubating future leadership, there has been an incentive for political parties to invest in student politics which has ensured it remains a factor for reckoning in Indian politics.

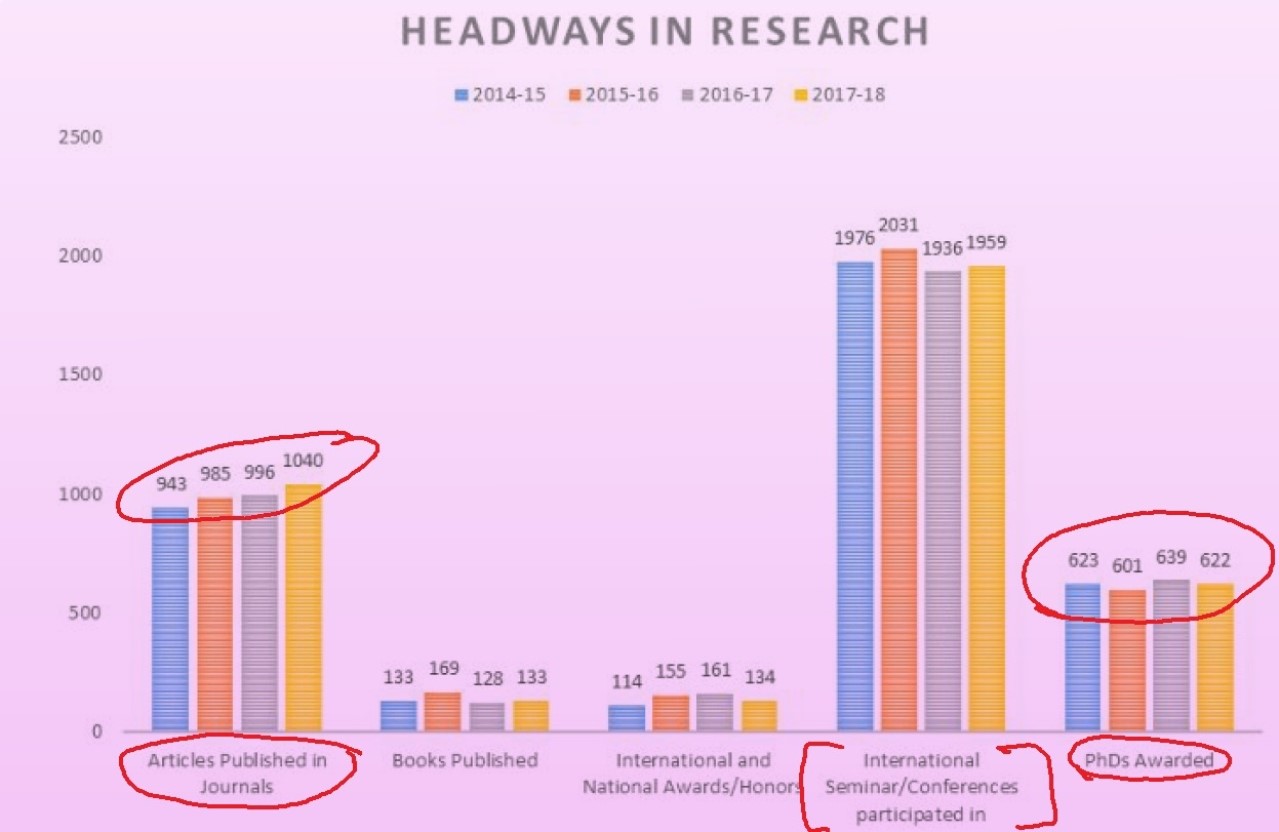

Since the ascendance of BJP in the political scene, many universities have seen intensified political activity by some student groups within the universities, most prominently, in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in India’s capital New Delhi. These have been not only severely disruptive in nature, but greatly undermined the character of the institution as a centre for academic pursuits. The decidedly subversive undertones of these students’ agitations permit no other conclusion than that these were steadily instigated by political interests who have stakes in fomenting unrest and disaffection against the Indian state in general and the present ruling dispensation in particular.

The manner and frequency with which every other issue has been appropriated by students to create ferment and engineer ‘protests’ are certain indication of an ongoing ideological battle rather than genuine grounds of discontent. Irrespective of the supposed cause behind the agitations, almost all of these were marked by quick escalation into violence and lawlessness and many of the ‘student leaders’ who were prime enactors of these agitations were found to have raised slogans inimical to India’s national integrity, an indictable offence under India’s sedition act[2].

Alleged ‘crackdown’ by government on university campuses

In spite of the soundbites generated by the media around them, it would be erroneous to assume that popular democratic opinion is reflected in these numerous students’ agitations over the past 4–5 years. At the opposite end of the political spectrum these would appear much rather as attempts to hijack the democratic process through intensive activism and loud propaganda, overriding the sentiments of the silent majority whose faith apparently stays invested in the incumbent government re-elected with a comprehensive mandate earlier this year.

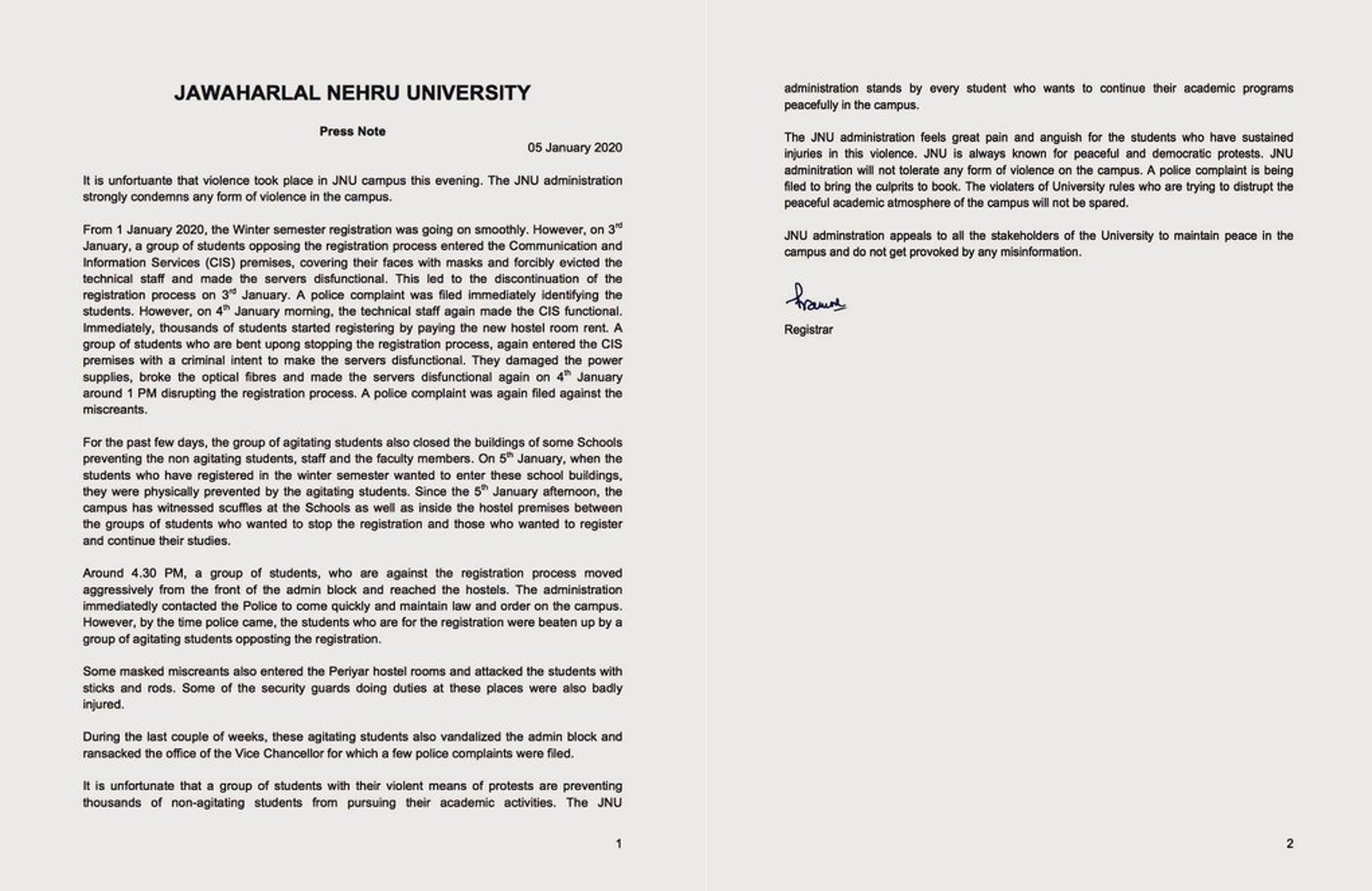

It is moreover wrong to infer that the stands assumed by the protesting students on issues are the same held among the larger body of students. Behind the fancy catchphrases of ‘Diversity, Democracy and Dissent’ lies the ugly truth that there have been several instances of students who wished to sincerely pursue studies and dissociated themselves from the political activist faction having faced harassment from the disruptionists for not supporting them and being prevented from attending classes and appearing in exams. In the most recent imbroglio in JNU, students were prevented from registering for the upcoming session by students’ groups adamant on continuing the stir against the fee-hike, apparently dissatisfied in spite of the partial roll-back by the government. According to the statement of the university administration (see Pic. 3), agitating students used violent means to disrupt the registration process by vandalising the registrar’s office, and later letting in masked, armed miscreants into the hostels and physically assaulting students who were opposed to their agitation. But for all the sloganeering on these vaunted ideals, JNU’s indicators on ‘progressive values’ would render this presumption hollow[3].

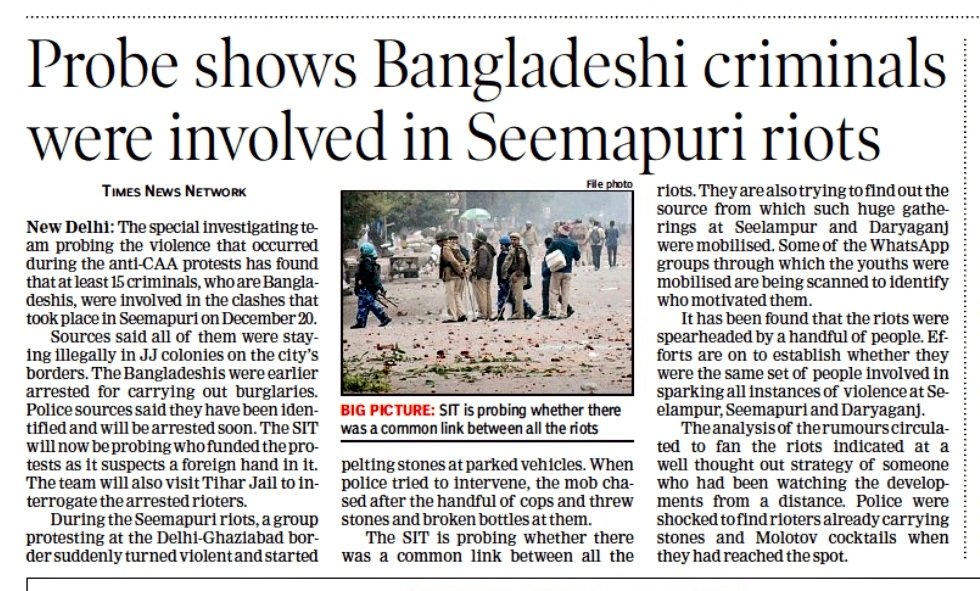

The government and law-enforcement authorities are faced with the unenviable challenge of isolating disruptive elements within the universities without hurting the interests of the bona fide students in these institutions. The task becomes all the more difficult as definite evidence surfaces of involvement of goons acting at the behest of political handlers[4] and radical Islamist organisations like PFI[5] in orchestrating attacks on the establishment and destruction of public property, and of ‘outsiders’ having infiltrated JMI university posing as students in the recent agitations against CAA. Another troubling aspect was the patent Islamist sympathies of the protesters whipping up passions along communal lines contrary to their purported humanistic concern.

Allegations are rife as conflicting images emerge from various media sources, both of rioting ‘students’ indulging in arson, stone-pelting, raising separatist slogans and violently assaulting stationed personnel, as well as the use of force by riot control forces. For the present purpose however it is relevant to ascertain the nature of the ‘protests’ and the grounds and proportionality of the police actions in the campuses.

Earlier in November, the Delhi Police firmly refuted allegations of use of any undue force in the action at JNU for controlling students protesting the ‘steep’ fee-hike. On December 9, Hundreds of irate students kept steadily swarming in at the All India Council of Technical Education (AICTE), the venue of the varsity’s convocation, surrounding the premises and keeping the HRD Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal ‘Nishank’ stranded there for almost 6 hours. As swelling numbers of students started bodily pushing their way through the thin police lines breaking even the barricades, law enforcement authorities were obliged to deploy around 600 anti-riot personnel to contain the situation.

Just in the previous week, on the pretext of a proposed fee-hike, students had commandeered the campus in a coup d’état of sorts, slapping locks on the gates of several varsity buildings and paralysing the administration. Students resorted to criminal intimidation detaining the Dean of Students (DoS) who had medical distress, denying access to the ambulance and later preventing it from carrying the patient away.[6] They also held a female professor hostage for 30 hours and barged inside the residence of another professor terrorising his family, and in one case snatched away the child of a teacher in order to blackmail the administration and coerce the resignation of some JNU office-bearers.

In assessing the appropriateness of force employed by law-enforcement authorities it must be borne in mind that university students are adults and legally liable. They are able-bodied and organised youth who can potentially endanger the lives and limb of personnel, and become a menace to citizens if allowed to run amok as a mob.

Accusations continue to fly thick between the lobbies for and against CAA in the ongoing stir, and the media has played no insignificant part in the elaborate agitprop to incriminate the authorities and the incumbent government. The police however maintained that no disproportionate force was used. Strictly from the legal standpoint, the use of force by police may have been justified and commensurate.

There are reports of unrest over CAA from various universities in India, but opinion among students remains clearly divided on the matter. At some places police took preemptive measures with heavy deployment and issuing strict warnings to university authorities and students to stay within the campus and eschew violence. At Lucknow’s Nadwa University, after a spell of stone-pelting by some students, police responded with firmness and the ‘protest’ dissipated after a brief standoff. In some cases educational institutions themselves responded promptly to the situation by acting against trouble makers among students and teachers to prevent unrest. There were skirmishes between students on the offensive and riot-police in the volatile Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) which were quickly quelled. 21 students were held. Students were ordered by the varsity to vacate the hostels as messages intercepted at AMU indicated that outsiders were instigating trouble within the campus. Violent protests were also reported from Allahabad University and FIRs registered against some 400 students involved in attacks on police personnel. Exams had to be cancelled at Allahabad and Bundelkhand universities, putting a question mark on the benefits of campus politics for students.

The other thing to consider is that CAA already has the force of law, enacted after due legislative procedure and parliamentary debates in the course of over 1-½ decades[7] and cannot in any way be seen as an arbitrary measure, as portrayed by protesters and sections of the media. The bid to turn it into a flashpoint for scoring political points therefore comes across as destabilisation of the democratic process rather than being a contribution towards it.

Universities as centres of indoctrination

From the very outset the Indian sociological and historical narrative suffered from the biases of west-centric Indological studies, which tends to narrate these according to how outsiders perceived and interpreted it, to fulfil and justify their own relation to it. In the decades following India’s independence, study of Indian sociology and history came to be dominated by academicians trained in the leftist ideological mold, who attempted to force-fit it into their pre-determined framework and distorted it to the extent that it is inconsistent with the socio-cultural reality of India. Leftist themes in depiction of Indian society, religion, culture and history have been predominant not only in academic arena but also in popular mediums of art, like theatre and film-making, and journalism and mass communication.

These readings about India, standardised and perpetuated through the dominant academia and mainstream media, have persisted in the discourse as well as in the perceptions of people both outside and even inside the Indian milieu. Though the established narrative has been challenged in many scholarly works over the decades, an alternative disquisition was neither admitted nor tolerated by those firmly entrenched within academic circles. Consequently, generations of Indians roughly over the past century have continued to be fed this as the standardised version.

With the proliferation of new-age information and electronic media, which has led to greater awareness and access to original sources of history and sociology, there has been a growing sense of indignation among a significant section of Indians over the lack of control over one’s cultural narrative. Demands for reassessment of the sociological and historical narrative have steadily gained ground, especially in respect of formal material for instruction, e.g. textbooks. These bids have expectedly met with strident opposition from among the academia, seen as a challenge to their intellectual position and pejoratively referred to as attempts at ‘revisionism’. The present government, touted as representatives of the ‘nativist’ interests, made some efforts to introduce alternate emic perspectives in history and sociology, but these led to a hue and cry over ‘distortion of history’. It is a matter of continued debate whether the education system as a whole was hitherto a mechanism of indoctrination[8] or with the introduction of alternative narratives runs the risk of turning into one.

Much of the political rhetoric has oscillated between these two sides of the political divide, as well as a third which is neither quite ‘right’ nor ‘left’ of the discourse, but akin to what is commonly termed as ‘historic negationism’, which may be identified with the centrist position. These in turn are reflected in campus politics. But though several universities have retained a healthy mix of representatives among students and faculty from all persuasions, some notable universities like JNU and Jadavpur University (JU), turned into breeding grounds of leftist politics, intolerant and violently opposed to any opinion at odds with their own. Edged out of contention in national politics, the communist parties’ last bastion are the handful of universities in which a contrarian, disconnected, dystopic universe thrives among students, picked and groomed through a systematic process of exclusion of alternative viewpoints and indoctrinated to be useful idiots in the hands of subversive political agendas. Some others, like JMI and AMU are characterised by a political position wedded to the Islamist worldview, which however finds sympathetic vibes in the ‘regressive left’ (as in the recent protests against CAA.)

The National Students’ Union of India (NSUI) is the student wing of the Indian National Congress (INC) and similarly, the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP) is the student wing of Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS)[9], which could respectively be termed ‘centrist’ and ‘rightist’ in terms of ideological delineation. Both have seen success at polls in several universities around India, and votaries of both known to have indulged in intense activism and violence on occasions, handled with physically rough to brutal police action[10] some of the times. Clearly, the action against students in the CAA protests is not unprecedented. However in JNU, the NSUI has not been a force of reckoning, the primary counter to the left being presented by ABVP.

ABVP is the biggest student organisation in India with around 3.175 million members as of 2016, active in around 790 campuses all over India. Former Finance Minister, Mr Arun Jaitley, had his ideological foundation in ABVP. The Delhi University Student’s Union (DUSU) has ABVP members at its prominent posts.

The Students’ Federation of India (SFI) is the student political organisation affiliated to the Communist Party of India–Marxist (CPI-M) while the All India Students Association (AISA) is another leftist students’ organisation, the student wing of Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation (CPI-ML). The All India Students’ Federation (AISF) is another leftist student organisation which has as its declared purpose ‘scientific socialism’. They have been at the forefront of the campaign against the commercialisation, ‘racialisation’, ‘degradation of the education sector’ and for the protection of the public education. Together these leftist student groups have won most of the Jawaharlal Nehru Students’ Union (JNUSU) elections. The Campus Front of India (CFI) is another student organisation active in JNU affiliated with the controversial Islamist organisation, Popular Front of India (PFI). Apart from CFI, JNU has several other student groups with stated Islamist goals. It is worth deliberating whether these political outfits with religious leanings can legitimately be allowed to function in JNU.

It has long been felt that the only way to break the leftist vice-grip over education is to throw the education sector open to competition, and precisely this the reason for the virulent reactions of leftist students’ groups against any move to make the institutions more competitive, e.g. in respect of fees. But how reasonable are their grounds? Most importantly, how useful is the education to the individual and the nation that is provided at such a tremendous expenditure of public money[11]?

For improving the quality of education in Indian universities undoubtedly a major overhaul of curriculum is required, making the courses more vocation-oriented. Specifically in respect of JNU, it is essential to re-emphasise academics and de-emphasise politics. In this connection it is important to mention that in the Lyngdoh Committee Report[12], 86% of the students surveyed—who voted either way—answered with an emphatic ‘No’ to political-party interference in student-body elections.

Employability and education

JNU retains its position as a premier institution for liberal arts, consistently rated among the best, particularly in the fields of humanities, social studies and international relations. It has given the country some of the best minds, among them, two of the current cabinet ministers, Nirmala Sitharaman[13] and S. Jaishankar[14], and Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences awardee, Abhijit Banerji. However, incessant politicking has caused an observable fall in its standards. Its reputation as a serious institution for academics took a beating with the ‘tukde-tukde’[15] episode and marked the inflection point in the relationship between society and students.

The highly ideologically charged and politically motivated section of students of JNU are overwhelmingly from the humanities departments at JNU. Most politicians who have come out of JNU—if not all—have been from the humanities stream. Only 25% of all JNU faculty is from the sciences, seen as an unhealthy ratio for the smooth functioning of any university[16] and raises questions about the ‘usefulness’ of studies. The aspect of usefulness alone however does not define the purpose of education. There is a range of knowledge that covers the entire cognitive and intellectual capacities of the human mind and the evolution of our collective awareness which cannot be evaluated solely on pecuniary criteria. These are indispensable for determining the conscious course of human society as a whole. Skill-based knowledge and perception-based knowledge form distinct aspects of human development and do not preclude each other’s relevance. However, it is important to preserve a balance between patronising purely intellectual pursuits and providing gainful education to raise a productive population.

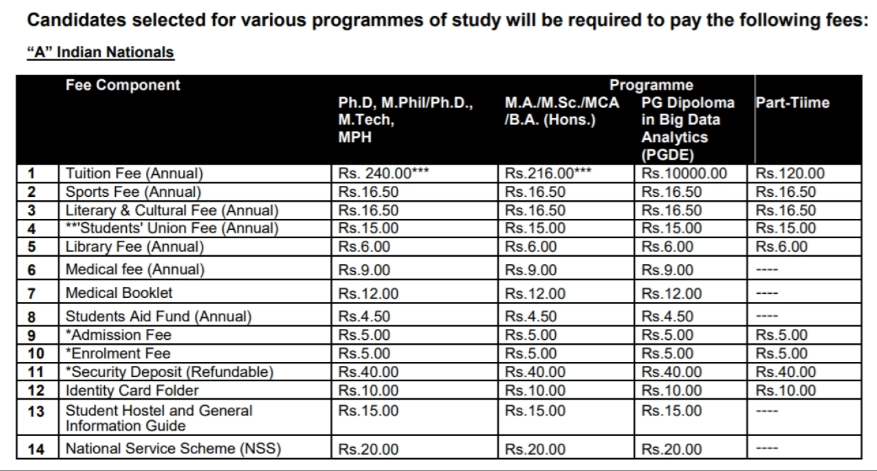

To restore some proportion the government made efforts to introduce courses in engineering and management in JNU. Until very recently, JNU offered only academic and research-related subjects and did not offer any professional courses. Yet JNU students launched into another bout of protest over the introduction of a professional course (MBA)[17] in March 2019, over the high cost of the course. Despite the fact that students were enrolling for the course from all over India, including CAT qualifiers, and the fees were at par with other government-funded institutions like IITs and IIMs, students went on hunger-strike because it went against the communist-socialist ideological grain.

Students of Humanities glorify dissent as a mode of bringing change and improving society and counter the ‘usefulness’ argument saying that science students lack the faculty of ‘critical thought’. But apart from the fact that there is no credible basis for such a claim, this is a slippery slope argument that dignifies self-conceited opinionatedness and carping over sincere pursuit of academics. In reality, formal study of perception-based subjects is not free of ideological influences and therefore its inferences not incontrovertible unlike scientific conclusions.

The kind of intellectual indulgence that calls for dismemberment of India, support for terrorists convicted by due procedure of law, and celebrates the killing of Indian soldiers at the hands of naxalites, are offending to common sensibilities and makes students the objects of popular anger and disdain. Freedom is undoubtedly an inviolable right, but the kind of expressions of freedom that cock a snook at the very ecosystem that supports it has drawn tremendous Public ire with demands to close down the university.

Fee-hike

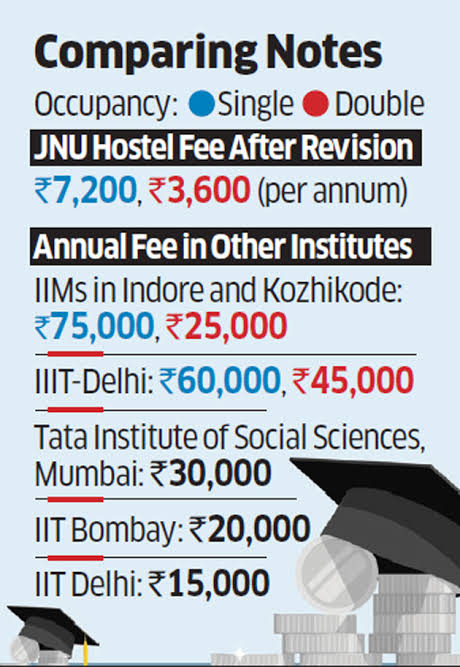

The validity of the students’ protests also demands scrutiny. A comparison with fee structures at all government-funded universities would show that JNU’s present fee-structure is untenable, and that the hike was not only justified but necessary and long overdue.

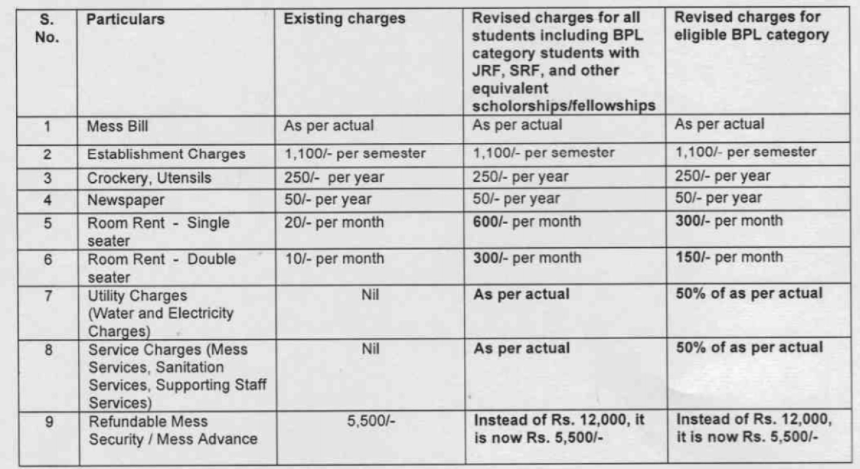

To put the matter into perspective, the provisions proposed an increase in hostel fees and installation of water and electricity meters on hostel premises, and set a dress code for hostellers. This immediately met with an outcry from students at the 300% proposed hike . But a closer look at the base rates that this applies to—Rupees 20/- per month for a single accommodation and Rupees 10/- for double occupancy, a meagre 0.28 cents and 0.14 cents respectively being paid for over 3 decades—would give it a much more reasonable appearance than the demagoguery surrounding it would lead us to believe. These were increased to Rupees 600/- ($8.42) and 300/- ($4.21) respectively[18] along with an additional charge of Rupees 1,700/- ($24) for sanitation and maintenance and doubling of the mess charge.

These rates make the charging of fees seem altogether superfluous. But the justification for this lies in the 2017-18 annual report of the university, which showed that around 40% of JNU students come from families with a monthly income below Rupees 12,000/-[19]. This however does not account for the fact that about 60% students who can clearly afford much better continue to avail subsidised education at the expense of the public.

The undeniable populist appeal of the protest against fee hike saw student groups across ideological lines band together on the ‘cause’.[20]

Even at the increased rate, JNU fees would be Rs 7,200 and Rs 9,700 for double and single occupancy respectively, lower than comparable government-funded institutions such as Delhi University, Jamia Millia or Ambedkar University. Government-funded “minority” colleges such as St Stephen’s charge as much as Rs 60,000 per annum. JNU authorities defended the fee hike saying that as many as 89% of its hostellers get financial aid[21] and its tuition cost still remains lowest in the country. Since students receive a stipend for studying at JNU, education in JNU is completely free for all practical purposes.

The demand of protesting students therefore is for free lodging and board, which goes far beyond what is reasonable and unknown in any part of the world (case for instance, Germany.) There is no excuse for students who find JNU hostels too expensive to not consider moving out and working part-time to pay for their expenses as students do worldwide. The sense of entitlement that demands freeloading as a right is bound to raise the hackles of the tax-paying citizenry. It is an example of socialist elitism at the worst.

Moreover, the self-image of JNU students as being part of a centre of unrestrained liberalism (including sexual permissiveness)[22], [23] conflicts with the discipline characteristically associated with academic institutions. Concern has been raised in an internal dossier that the institution has become a centre of organised sex racket (sic.)[24]

Part of the students’ resentment was on account of dress codes, restrictions on visitors and so-called “curfew timings” in the new regulations. While impositions on personal freedom can be grating as adults, the institution has full right to impose its rules. If students treat higher education as extended childhood and expect the institution to play nanny by maintaining, cooking and cleaning for them, they cannot complain at being asked to abide by its rules.

Student stipend system

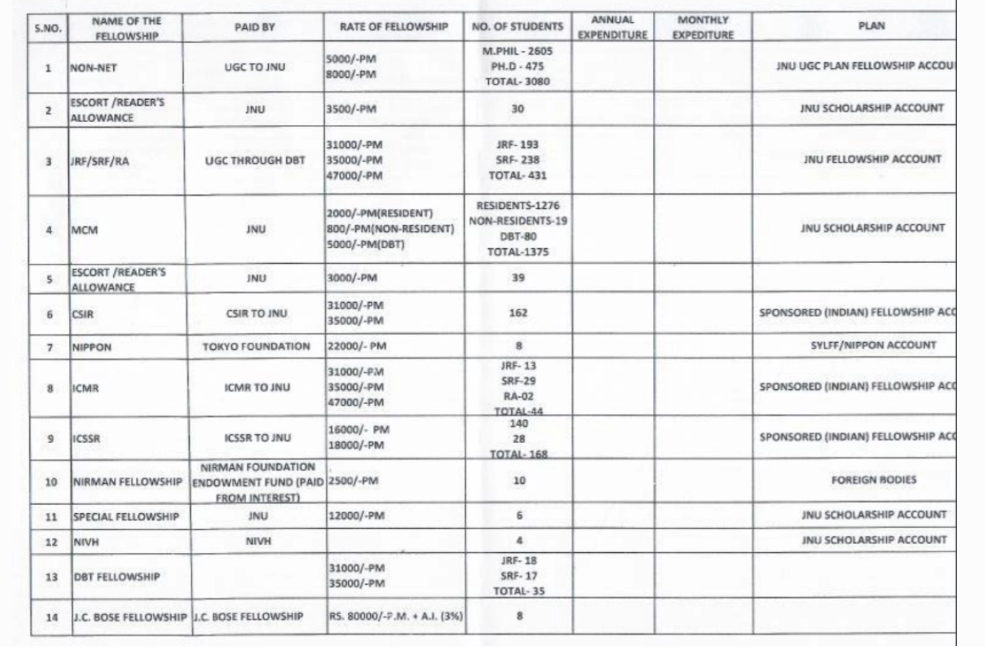

Ph.D. and MPhil students at JNU receive fellowship (SRF and JRF) from UGC. Students who clear UGC-NET get additional allowances like HRA, normal expenses, etc. from UGC.[25] All students pursuing master’s courses from JNU are eligible for student loan which can be repaid on getting employment or getting admission in a doctorate course.

Some details of scholarships received by students are given in the table above, according to which, 3,080 students get Rs 5,000–8,000 per month; 1,375 students get up to Rs 8,000–5,000 per month, 431 students get Rs 31,000–47,000 per month, and so on.

Overall Perspective

Political motivations are discernible from the choice of issues in students’ movements[26], particularly in recent years. But in spite of the traction these have received in mainstream media, their influence in national politics is limited on account of increased presence of social media as a true reflection of public opinion. These have reduced the throwing around of terms like ‘Hindu Rashtra’ and ‘Hindu nationalism’ to mere rhetorical matches since the electorate, more keenly aware of the dynamics at play behind political posturing, has seen through the rabble-rousing and are more alive to what serves their interest as individuals, communities and a nation.

The measures to reclaim JNU from being run by unruly students and restoring administrative authority cannot be seen as a curtailment of free thought. These are unlikely to have any detrimental effect on expression or exchange of ideas both within the university and in interactions with other universities and the outside world.

In conclusion it may be said that the exercise of right of dissent through student movements will continue to play a role in political opinion making. But these will be increasingly counterposed by strong public opinion, both in social media interactions and show of numbers on streets, which will act as a powerful counter to motivated ideological groups from holding the nation to ransom in the name of (their) freedom of opinion. Instead of the shrill pitch of a closed but voluble group, viz. the students in the present case, manipulating media space to their ideological imperatives or political motives, the discourse will likely grow more representative, with a lively variety of opinions from a spectrum of social groups having a free playing field. In any event, democracy will not suffer.

[1] Interestingly, in Jamia Milia Islamia (JMI), the hotbed of the recent anti-CAA protests, student association elections are denied even in the present. It is a curious form of dissonance which does not question an autonomous university for curtailing this ‘democratic right’ of the students whilst upholding the same in case of the students’—singularly uninformed—protests against CAA.

[2] The interference between ‘freedom of speech’ guaranteed by the constitution and the sedition act (Section 124A I.P.C.) has long a mootable point among jurists. A 1951 order of the Punjab High Court ruled the section to be ‘unconstitutional’ and an Allahabad High court order of 1956 concluded that it struck at the very root of free speech. The latter was however overruled by the Supreme Court of India in 1962 which held that “speeches against the government or political parties is not illegal”, but upheld that it is applicable to “separatism by persuasion or force”. It is under the latter description that the acts of the JNU ‘student leaders’ fall.

[3] In 1990, students of JNU came out in protest overwhelmingly against the VP Singh Government’s attempt to implement the recommendations of the Mandal Commission. Again, in the aftermath of the Babri Masjid demolition on December 6th, 1992, the ‘outrage’ was meagre and muted. On the other hand, student leaders on the Left in the not-so-distant past, made capital of the protests, say, against the Delhi Milk Scheme (DMS) price hike, as recalled by former students who were not on the Left or who left the fold after JNU.

In respect of empowerment of women and their participation in politics it was found that 50.9 per cent of women did not participate in political activities as against 24.8 per cent among men. Though the current JNUSU president is a woman, but ‘Overall, women are far less likely to participate in political events on campus. This is an important finding, because JNU is often perceived as a leading institution in terms of gender equality and inclusiveness.’ (Martelli and Parkar)

The same holds for parameters of social inclusion: “[In] JNU, Scheduled Caste (SC) groups like the UDSF, BAPSA, and BAMCEF constantly accused communist-led organisations of having an outrageously upper caste-led national leadership.” In the ethnographic evidence from their fieldwork, Martelli and Parkar found that ‘sections of the North Indian Muslim population also accuse Marxist organisations of creating ‘Muslim posts’ (for instance, the seat of Joint Secretary of the union was occupied by a Muslim student in 2012, 2013, and 2014) in order to secure their vote’. (‘Battleground JNU’, Sudeep Paul)

[4] Delhi police made arrests of ten persons none of whom were however JMI students and all had criminal background.

[5] According to an intelligence reported shared by the Indian Ministry of Home, “Some political parties [names withheld considering the gravity of the case] ignited the violent acts at various places, letting opportunities to sleeper cells of extremist and militant Islamic fundamentalist organisations, Popular Front of India (PFI) and Students Islamic Movement of India (SIMI).”

[6] Such arm-twisting of authorities by students to escape disciplinary action for violations are by no means rare in JNU, nor for that matter unknown in other parts of the world, termed ‘academic entitlement’.

[7] The Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) first passed the lower house of parliament in December 2003. The bill had at that time received the full support of the Indian National Congress.

[8] Owing to the predisposition of the academicians, most universities retain a predominantly leftist outlook on most issues.

[9] Their link to BJP is through the Sangh Parivar.

[10] Police lathi-charge protesting ABVP members in Bihar; UP Police brutally Lathi Charge ABVP protesters in Lucknow; Police lathi charges ABVP activists during protest march in Thiruvananthapuram; Police lathi-charge NSUI students during rally in Jaipur

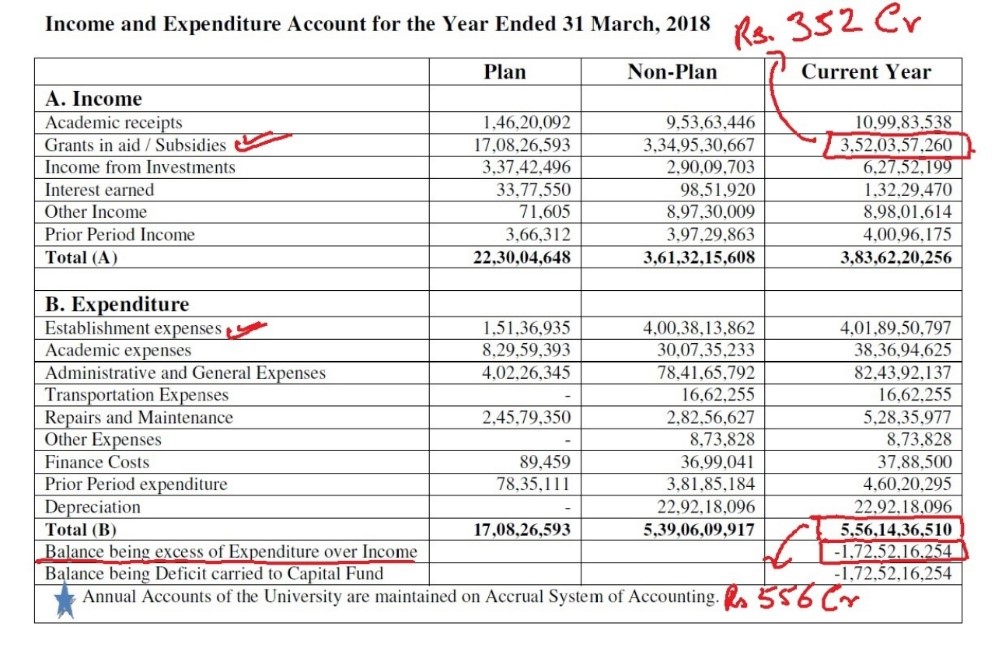

[11] According to one estimate educating a JNU student costs a whopping Rupees 6.95 lakhs per year. The university spends about Rs 556 crore per year on its functioning for around 8,000 students enrolled at the university.

[12] Report of the committee formed by the Ministry of Human Resources Development, ‘To Frame Guidelines On Students’ Union Elections In Colleges/Universities’

[13] Union Defence Minister (until May 2019), presently, India’s Minister of Finance and Corporate Affairs

[14] Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, India’s External Affairs Minister

[15] Refers to the slogans raised in a gathering of JNU students headed by JNUSU president Kanhaiya Kumar, calling for the dismemberment and ruin of India and heroizing terrorists convicted by the Indian judiciary.

[16] The Banaras Hindu University (BHU) in contrast offers a wide range of scientific and research-related subjects and highly vocation-oriented courses.

[17] An engineering course with selection on the basis of JEE is also being introduced.

[18] Following the protests these were revised to Rupees 200/- and 100/- respectively.

[19] That is to say, at least on paper

[20] ABVP later withdrew support after the government agreed to a partial roll-back with an additional grant from UGC of Rupees 6.7 crores.

[21] According to the statement of Prof Satish Chand Garkoti, JNU Rector II, out of the 6,000 students living in hostels, 5,371 students receive financial assistance in the forms of fellowships and scholarships. Referring to the new service charge of Rs 1,700 per month for hostellers, he said that “the University Grants Commission (UGC) no longer allows payments of salaries of contractual employees of the hostel from the salary head of the budget. The number of such employees in the hostels is over 450. The UGC has given clear instructions to JNU that all shortfalls in the non-salary expenditures should be met by using the internal receipts generated by the University. Thus, there is no alternative for the administration than to collect service charges from the students.”

[22] It recently came to light that one of the research papers submitted at JNU was on a popular pornographic animated character ‘Savita Bhabhi’. While this may be an exception and one may argue that exploration of metrosexual mores and taboos may form a subject of research in the liberal arts, the viability of sponsoring such ‘research’ with public funds is questionable and cannot but be rankling to the average tax-payer.

[23] ‘Kiss of Love’ campaign in JNU

[24] In 2016, a female student was allegedly drugged and raped by an AISA activist in the JNU hostel. In an early morning ‘raid’ by wardens, 13 girls were found in the men’s hostel. Though JNU has coresidential hostels for men and women, this was a strictly men’s hostel.

[25] According to enrolment numbers around 57% of students (4,359 out of the total strength of 8000) at JNU are pursuing either Ph.D. or M.Phil.

[26] Protest-meet in JNU over Ayodhya Verdict; Students clash in JNU at Article 370 event

Cover Picture: ‘Protesters shout slogans at a demonstration against Indias new citizenship law in New Delhi on December 19, 2019.’ (Source: Sajjad HUSSAIN/AFP via The Statesman)

Featured Image: ‘Creatives against CAA’ by The Cognate