By Smita Mukerji

Read the previous section of this series here.

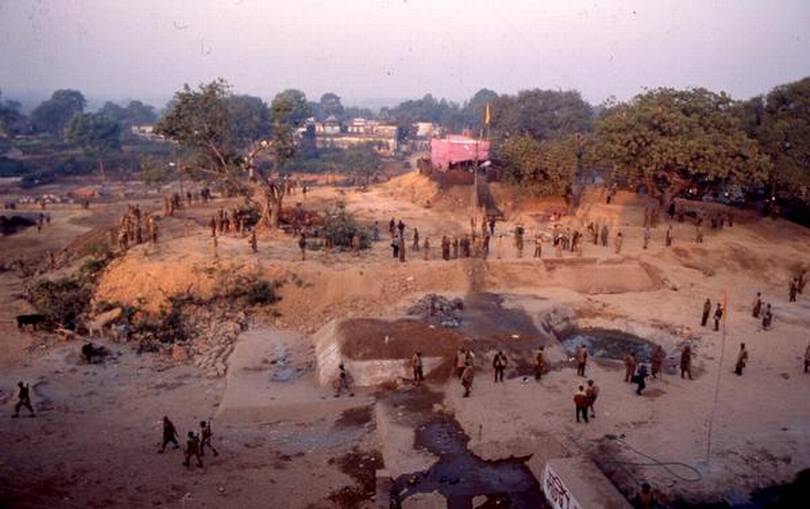

On November 9, 2019, the Supreme Court of India delivered the landmark judgement deciding the Rāma Janmabhūmī–Bābûrī Masjid matter, pending in the form of dozens of suits with the courts over almost seven-decades. One of the key factors in the adjudication of the title suit was the status of possession of the site through the centuries.

In matters of faith, continuity of practice of a tradition is of critical importance in ascertaining right of the practitioners over a place sanctified by the tradition. It is testimony to the unwavering faith of Hindus, that in spite of religious oppression over the centuries of Islamic rule, they persisted doggedly with their acts of devotion at the site, even when it was expropriated from them, which made it possible to establish that the site has remained inextricably linked with an article of faith over at least one millennium continuously, attested through numerous sources.

Dr. Rajendra Prasad, the first President of the Republic of India, while inaugurating the Sōmanātha temple on May 11, 1951 said:

“By rising from its ashes again, this temple of Sōmanātha is to say proclaiming to the world that no man and no power in the world can destroy that for which people have boundless faith and love in the hearts.”

Millions of unnamed Hindus repaired to Ayōdhyā, day after day, over months and years and centuries, with their steadfast observances, as per the sacred legend recounted in the Purāñas, at the Janmabhūmī site enshrined in their hearts as the birthplace of Śrī Rāma, earmarking it in perpetuity.

Sir James Scorgie Meston (Lieutenant Governor of the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, 1912-18) in the course of an enquiry conducted at Ayōdhyā remarked:

“The whole area of Ajodhya is wrapped up in their scripture and earliest traditions with the history of Rama. Probably the most revered of all the incarnations of the godhead; and the story of Rama and Sita is the most familiar and the most sacred episode in their literature. It is very difficult therefore for any one who is not a Hindu to appreciate the reverence which they feel for the holy ground of Ajodhya.”[1]

The movement of ‘bhakti’ or resolute devotion born of deep emotional attachment to the Divine and its manifested forms revered among Hindus, arose concomitant to Islamic invasions in mediaeval India that gave Hindus strength to tide over the most adverse period abiding in their dearly-held ancestral traditions in the face of the most cruel persecution. Among the innumerable saints of this spiritual movement was one of the greatest devotees of Śrī Rāma, Gōswāmī Tulasīdāsa (~1532–1623 C.E.)

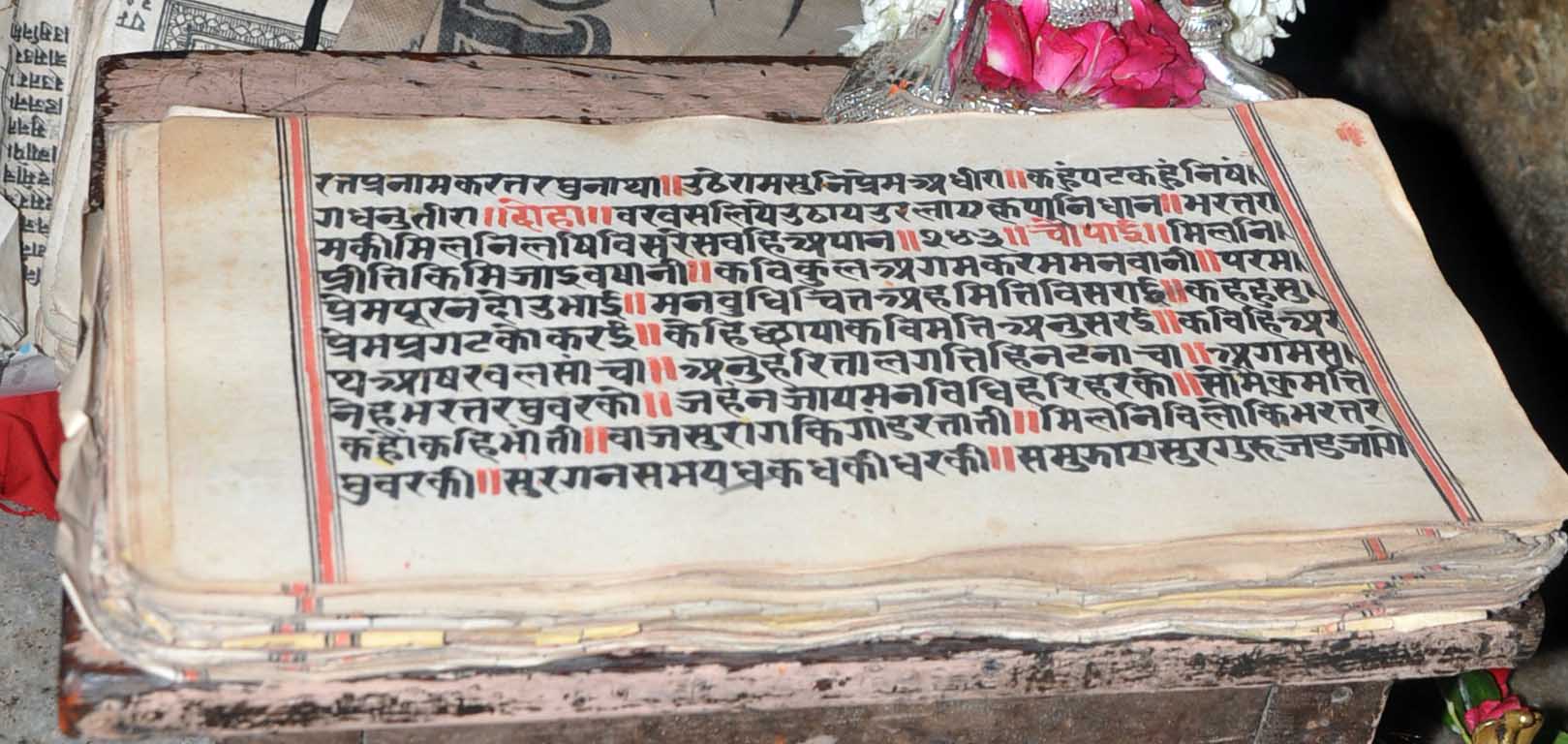

On the śukla (waxing moon) navamī of the month of Ćhaitra of Saṁvat 1631 (April 9, 1574) Tulasīdāsa commenced the composition of his magnum opus ‘Śrī Rāmaćaritamānasa’, the epic poem recounting the life of Śrī Rāmaćaṇdra in the language of the common folk ‘Awadhī’.

चौपाई :—

सादर सिवहि नाइ अब माथा । बरनउँ बिसद राम गुन गाथा॥

संबत सोरह सै एकतीसा । करउँ कथा हरि पद धरि सीसा ॥

नौमी भौम बार मधुमासा । अवधपुरीं यह चरित प्रकासा ॥

जेहि दिन राम जनम श्रुति गावहिं । तीरथ सकल तहाँ चलि आवहिं ॥

असुर नाग खग नर मुनि देवा । आइ करहिं रघुनायक सेवा ॥

जन्म महोत्सव रचहिं सुजाना । करहिं राम कल कीरति गाना ॥(॥बालकाण्ड॥ १.१.३४.)

“I bow humbly to Śiva as I begin this narration of the delightful tale of Rāma; in this Saṁvat year of 1631, placing my head at the feet of Hari; on Tuesday, the navamī of the sweet month of Ćaita, in the city of Awadh I reveal this story; on the day it is said Śrī Rāmaćaṇdra was born, the time when the spirits of all places of pilgrimage converge here; the demons as well as serpents, aerial beings and humans, saints and gods, all arrive to be in attendance on the best among the Raghus; while the noble observe the grand festival of the birth of Rāma singing hymns of his glory.” (Bālakāṇda, 1.1.34)

In the subsequent lines Tulasīdāsa describes the immense crowd of pilgrims at Ayōdhyā:

दोहा/सोरठा

मज्जहि सज्जन बृंद बहु पावन सरजू नीर ।

जपहिं राम धरि ध्यान उर सुंदर स्याम सरीर ॥३४॥“Thronging multitudes of pious devotees bathe in the purifying waters of Sarayū with the name of Rāma in their lips and their hearts fixed on his enchanting dark form..”

दरस परस मज्जन अरु पाना । हरइ पाप कह बेद पुराना ॥

नदी पुनीत अमित महिमा अति । कहि न सकइ सारदा बिमल मति ॥१॥“The Vēdas and Purāñas proclaim that all demerits are expunged by the mere sight of Sarayū and the touch of its waters, and by drinking and bathing in it. Such is its immense grandeur that herself the Goddess of Learning with her pure intellect cannot successfully describe the holiness of this river.”

राम धामदा पुरी सुहावनि । लोक समस्त बिदित अति पावनि ॥

चारि खानि जग जीव अपारा । अवध तजें तनु नहिं संसारा ॥२॥“This picturesque city that elevates one to the abode of Rāma (Vaikuṇṭha) is most pleasant, celebrated in all the worlds for its holiness; those from the four categories of animate creatures[2] that the world is swarming with, are freed forever and must never return to the world, if they cast off their bodies in Awadh.”

सब बिधि पुरी मनोहर जानी । सकल सिद्धिप्रद मंगल खानी ॥

बिमल कथा कर कीन्ह अरंभा । सुनत नसाहिं काम मद दंभा ॥३॥“Knowing it to be in every way charming, the bestower of exaltation and a mine of auspiciousness and felicity; I begin this sacred story, which annihilates lust, delusion and egotism.”

These lines in ‘Rāmaćaritamānasa’ where Tulasīdāsa provides the background of his composition are significant, as it affords us a contemporary vision of Ayōdhyā which was a populous city abuzz with religious activity in 1574 C.E. It describes the scene and the influx of a large number of pilgrims on the occasion of Rāma Navamī making it a “grand festival” (‘janma mahōtsava’). It confirms that the observance of the age-old ritual described in the Purāñas, of devotees bathing in the Sarayū and paying obeisance to the deity of the city, Śrī Rāma (‘āyī karahi Raghunāyaka sēvā’). It may be debated that if the temple which marks the birthplace of Rāma was not there in this time, where did the pilgrims perform their devotions? And if it was the memory of the Janmasthāna that pulled the multitudes to Ayōdhyā, it is direct substantiation that irrespective of a temple at the spot, the location and the significance of the place remained firmly and unmistakably imprinted in the conscious memory of the people through the centuries.

But curiously, even if there is no mention of a temple in the Rāmaćaritamānasa, the great bard does not remotely allude to any mosque there either. He does not refer to a distinct spot marking the birth-site, unlike ‘Awadha Vilāsa’ of Lāl Dāsa (completed 1675 C.E.) which mentions the seat of Rāma’s birth, while omitting mention of a temple or an idol:

नोमी चैत मास उजियारी । व्रत करै दरसन नर नारी ॥

जो बालक परसै जन्मासन । रोग दोष गृह व्याधि बिनाशन ॥“On the ninth day of the bright lunar fortnight of the month of Ćaitra, men and women undertake fast and obtain a vision [of Rāma]. Children who touch the seat of Rāma’s birth are rid of all ailments, deformation, debilitating natal stars.”

Tulasīdāsa in contrast speaks of placing his head at the feet of Hari on the auspicious day of Rāma Navamī before beginning his best-known composition. A very likely scenario would have been, that after ablutions and a visit to the Janmasthāna temple as per the prescribed purāñic rituals, he set about his design in a blissful state of mind. He would have no reason to not have gone through the rituals while being in Ayōdhyā on the most important annual celebration marking the birth of his chosen ideal, just as a disrupted status of the place of birth of Rāma on that day could not have failed to elicit a twinge of sadness from him.

Tulasīdāsa rather spoke of the city of Rāma as very pleasing (पुरी सुहावनि), a mine of auspiciousness (मंगल खानी) and delightful in every way (सब बिधि पुरी मनोहर). His ebullient thoughts in the prologue of ‘Rāmaćaritamānasa’ describing the perfect beauty of Ayōdhyā lead one to only conclusion: that the Rāma Janmabhūmī temple was in situ at the time of Tulasīdāsa. This also explains why he had no cause to mention offering prayers at a specific seat of birth (e.g. the bēdī or janmāsana), simply because that would be part of the existing temple enshrining the vigraha of Hari. In some of the later accounts as opposed to this, as we shall see, the bēdī and other sacred vestiges that were in the precincts of the erstwhile temple are mentioned as distinct parts.

Tulasīdāsa lived in the time of the Mughal emperor Aḳbar (r. 1556–1605 C.E.) Another important source on the condition of Ayōdhyā in the latter half of the 16th century is Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubārak, author of the emperor’s official biography, Aḳbar Nāmā. In its concluding portion ‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, compiled roughly in the years 1590-1602 C.E., Abu’l-Fazl writes on Ayōdhyā:

“Awadh is one of the largest cities of India. It is situated in longitude 118°,6’, and latitude 27°,22’. In ancient times, its populous site covered an extent of 148 kos in length and 36 in breadth, and it is esteemed one of the holiest places of antiquity. Around the environs of the city, they sift the earth and gold is obtained. It was the residence of Rãmachandra who in the Tretã age combined in his own person both the spiritual supremacy and the kingly office.

At the distance of one kos from the city, the Gogra [Ghaghra], after its junction with the Sai [Sarayū], flows below the fort.”

(‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, Vol. II)

“He [Rāma] was accordingly born during the Tretã Yuga on the ninth of the light half of the month of Chaitra (March-April) in the city of Ayodhyã, of Kausalya, wife of Rãjã Daśaratha. At the first dawn of intelligence he acquired much learning and withdrawing from all worldly pursuits, set out journeying through wilds and gave a fresh beauty to his life by visiting holy shrines. He became lord of the earth and slew Rãvana. He ruled for eleven thousand years and introduced just laws of administration.”

“Ayodhyã, commonly called Awadh. The distance of forty kos to the east, and 20 to the north is regarded as sacred ground. On the ninth of the light half of the month of Chaitra a great religious festival is held.”

(‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, Vol. III)

The account in Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī not only confirms Tulasīdāsa’s narration that the celebration of Rāma Navamī in Ayōdhyā was a festival of enormous importance and proportions, but nails each one of misrepresentations of the EIH’s by providing direct corroborative evidence that Ayōdhyā was a big city and a teeming pilgrimage spot already renowned in the 16th century as one of the holiest places since ancient times, associated indubitably with the birth of Rāma and his residence. It also talks of the presence of a fort at an eminence in Ayōdhyā, the precise dimensions of the area considered sacred ground, and puzzlingly—though he mentions the (supposed) tombs of two Muslim saints[3], and another tomb possibly of the saint Kabīrdāsa[4] at Rattanpur (in present Faizabad district)—the Ā’īn contains not even a ghost of a mention of some mosque in Ayōdhyā.

We pause at this point in our story to scan the scene to take a look at the condition of Hindus and temples in the Mughal period.

A Brief Overview of the Condition of Hindus and Temples in the Mughal Period

During the Delhi Sultanate, though the conditions of jīzyāh afforded a frail safeguard that properties of non-Muslims who paid the religious tax would not be molested, and a recourse to justice under sharī’at, in case a place of worship of the Hindus was desecrated/alienated from them by the acts of Muslims, it forbade repairs and renovations of destroyed/dilapidated temples and the building of new temples.[5] However, under Mughal rule this seems to have been permitted generally and occasionally though express decrees. The other major condition of jīzyāh was that, though it worked as a bare check on Muslims from destroying Hindu properties and temples—which in reality was commonplace—these were not rendered free from intrusion as Muslims could gain admission in Hindu properties and temples at will and stay there and do as per their pleasure. Mughal royal farmāns effectively put an end to this practice.

Aḳbar was the first Islamic monarch[6] who strove purposefully to create a common citizenship for all his subjects[7] promulgating a series of orders to remove steadily all civil disabilities and discriminations against non-Muslims,[8] which marked a fundamental departure from Islamic state policy[9]. He is widely known for his unprecedented step, the first ever in the history of Islam, of abrogating the jīzyāh (March 15, 1564 C.E.)[10] He removed all restrictions on public worship by non-Muslims tossing out a basic Islamic objection that witnessing religious celebrations of kāfirs was a profanation to Muslim eyes and ears. Earlier in 1563, he had remitted the pilgrimage tax imposed on Hindus throughout his dominion at an enormous annual loss to the treasury[11] and banned the practice of making slaves of captives of war and their families[12] and their being forcibly converted to Islam (April 10, 1562).[13] This was widened to outlaw slavery altogether in 1582.[14] Poor parents[15] who had been compelled by poverty or excruciating hardship to sell their children were allowed to buy them back from servitude when they were in a position to pay. Kōtwāls in the towns were directed (general order recorded in Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī) to see that no restriction was placed on personal liberty (baṇd kardan) and that there was no purchase or sale of slaves.[16] It is clear from numerous instances that these were not merely pious wishes but laws strictly meant to be followed.[17]

A still more landmark law aimed at bringing parity among the citizens stipulated that, Muslims who had previously been converted by force and Hindu women forced to marry Muslims and embrace Islam, could be reconverted to Hinduism and the latter restored to their families (1580 C.E.)[18] But by far most injurious to the interest of Islam were the set of laws in 1593 permitting non-Muslims to make willing converts from among the faithful (considered a capital crime under Islamic law) just as the reverse was seen as a right of the Muslims.[19]

Aḳbar also promulgated an order forbidding marriages between Muslims and Hindus. Since Islamic law required that a Hindu girl be converted to Islam before marrying a Muslim it was not to be considered a genuine change of faith. In the converse case, the marriage of a Muslim woman with a Hindu was illegal as per Islam, and Hindu law, as understood then, did not sanction such marriages. Aḳbar therefore decreed that such conversion to Hinduism or Islam were based on passion rather than on religion and should not be permitted.[20] These laws struck at the very source of adding numbers to the flock of Mohammad and were bitterly resented by the Muslims.[21]

Explicit orders were issued allowing Hindus and Jainas to reclaim and repair their temples, restraining Muslims from lodging in their temples and rest houses (upāśrayas), preventing interference in their rituals, and even protecting them against ridicule by Muslims.[22] Strict orders prohibiting slaughter of animals on days sacred to Hindus and Jainas[23], i.e. Sundays and Thursdays, were issued by Aḳbar and Jahāṅgīr[24] and absolute ban placed on slaughter of cows[25] and by some accounts even capital punishment inflicted[26] on those who slaughtered cows[27] or killed animals on forbidden days (e.g. during paryuṣaña in Gujarāt).[28] Most of these measures went diametrically against Islam and were viewed by the ulēmā as an erosion of the Mohammedan faith.[29]

It is difficult to say whether these royal orders permitted Hindus to reclaim the alienated temple sites by actually demolishing a mosque standing over it. But we have one definite example of this having been done at Thānēsar, where Hindus destroyed a mosque built in the midst of a tank considered sacred by them and built a temple over it.[30] We are told by Sujan Rai (Khulāsat-ut-Tawārīḳh) that a temple at Achal Makani near Batala (Punjab) was rebuilt after the Muslim faqīrs had demolished it during a fight with the saṅyāsīs there.[31] Mughal biographer and noble `Abd al-Bāqī Nàhāvandi, in ‘Ma’ātir-i Rahīmī’ (written 1614-1616 C.E.), talks of an order apparently issued by Aḳbar in 1601 to prince Dāniyāl, who had been appointed to the province of Ḳhāndēsh, which read: “…to destroy the Jama Masjid at Asirgarh and raise [in its place] a temple on the pattern of Hindus and [other] infidels of Hindustan.”[32] Dāniyāl is said to have been “wise enough” to not act on the order and “whiling away time”.

Given the intrepidity that Aḳbar’s liberal policies afforded to Hindus and the massive works of temple re-/construction undertaken by them in his rule, at times enabled by definite imperial orders, and the great significance of Ayōdhyā in the hearts of Hindus, borne out from numerous contemporary records, it is impossible to think that, had the temple at the Janmabhūmī site been under the occupation of Muslims, there would no attempt to recover it by the several powerful Hindu princes and nobles. The descriptions of serene, sacred goings-on in Ayōdhyā apparently unmarred by any intrusive presence or structure militate against such a possibility.

We know from a sanad issued on Ramzān 15, 1008 A.H. (March 28, 1600) that Aḳbar had made a grant of 6 bīghās for the construction of Hanumān Ṭīlā in Ayōdhyā[33]. Kishore Kunal speculates that the land may have been awarded to the Rāmānaṇdī saint Rāmtīrtha.[34] The Viśwanātha temple at Kāśi was renovated under his auspices[35] and several hundreds of bīghās as tax-free lands were granted for the administration and maintenance of temples at Vṛndāvana and Mathurā[36], some grants as large as 200 bīghās[37].

Aḳbar issued certain denominations of coins depicting the Hindu deities Rāma and Sītā to mark his fiftieth regnal year, known as Rāma-Sīyā coins. Two of these, of half mōhûr[38] worth were in gold and a third of half-Rupee in silver.[39] The two gold coins depict Rāma and Sītā on the obverse. Rāma wears boots in his feet and a crown adorns his head, holding a bow in his right hand and an arrow in his left. Sītā is to his right shown following him. The coin kept in Cabinet de France is inscribed additionally with the words in Dēvanāgarī ‘रामसीय’ (Rāmasīya). The coins depict their departure to the forest. The silver coin, issued in Amardad 1014 A.H. (July 1605 C.E.), depicts Rāma and Sītā immediately after their marriage in Mithilā, shown walking barefoot, Rāma holding a bow in his left hand, but no arrow, and Sītā to his right holding a bouquet.

In order to infuse an air of catholicity in religious thought he established a department of translation which was entrusted with the translation of Hindu sacred texts into Persian. To extend toleration to Hindu religious books[40] he ordered several Sanskrit works to be translated into Persian, among them the Atharva Vēda, the Harivaṁśa, the Paṅćataṇtra, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaña.[41]

One of the most significant steps taken by him to secure the position of Hindus was to free them from being subjected to sharī’at by allowing their matters to be governed by separate personal laws[42] and own paṅćāyats. Hindu scholars knowledgeable in all schools of Hindu jurisprudence were appointed to decide cases of Hindus[43], a practice that appears to have been continued by Jahāṅgīr.[44]

But these emphatic steps, and several others taken by him to ensure compliance to the laws, ran directly counter to the tenets of Islam and its political aims, many of which fell in the realm of blasphemy, which so greatly distressed the Muslims that they heaved a sigh of relief at Aḳbar’s death.[45]

The bristling references to the emperor must be regarded with caution. These portentous accounts of the dire days of Islam were written by the scandalised orthodoxy incapable of grasping Aḳbar’s broadminded vision. These are counterposed by accounts of several contemporary Muslim writers that pay fulsome tributes to Aḳbar and do not speak of him as a persecutor of Islam nor a denier of its truth.[46]

Aḳbar was a declared imperialistic[47] with manifest expansionist ambitions. But he was an astute statesman who realised that the stability of his empire rested on the conciliation of the Hindus who constituted the majority of his subjects[48] and also the need to protect them from the predatory ways of the Muslims. The Mughal Empire, as any invader’s, was no doubt established through violence and large-scale bloodshed in some cases. But as far as foreign rule goes, none could be as beneficent towards the native population as Aḳbar’s regime, which gave Hindus a toehold to crawl back in a position of strength and reckoning in the power-equation. It would be a fit case of study and a far more worthwhile pursuit—instead of churning out vulgar diatribes that ignorant Hindu reactionaries today are typically given to—to acknowledge and learn from the life of this brilliant monarch, how he turned an Islamic polity, sustained on an army still largely Muslim—and rabidly so—to the best advantage of his non-Muslim subjects, to protect their freedoms and to gain from the culture he had come to rule, not just materially but spiritually. How far he achieved this purpose may be debated, but what is definitely to his credit is that he could have taken the path of least resistance and continued with the status quo, but did not.

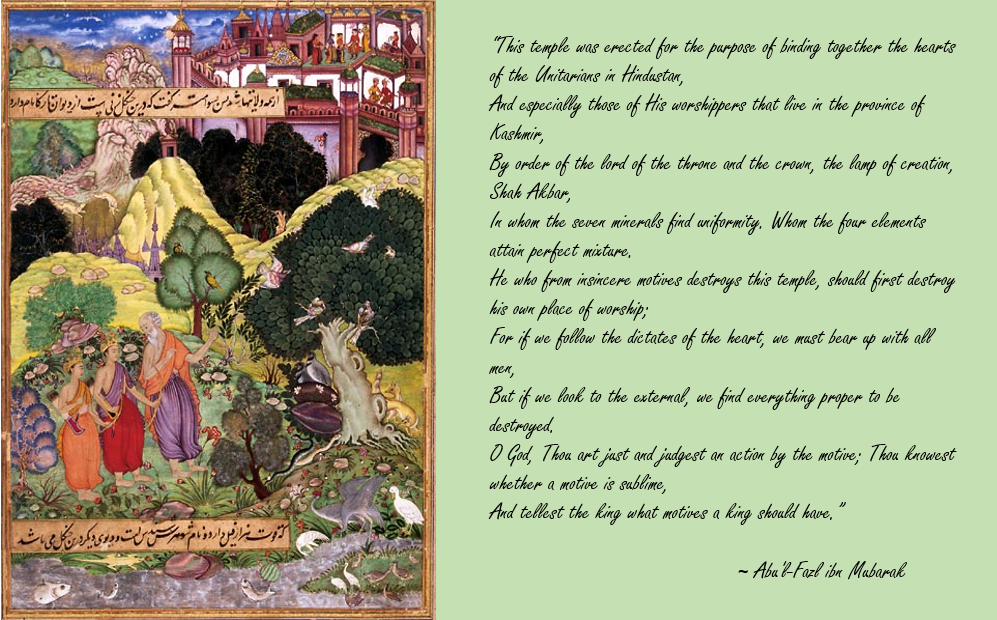

Cover Picture:

‘Vishwamitra brings Rāma and Lakśmaña to his hermitage’

Illustration from first Persian translation of the Rāmāyaña by `Abd al-Qadir Badā’unī, commissioned by Aḳbar (Source: Museum ‘Rietberg’)

Verses:

Inscription on a temple in Kashmir, attributed to Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubārak (found in ‘Durār-ul Manshūr’ Tazkīrāh by Muhammad `Askari Hussaini of Bilgram), quoted by Heinrich Blochmann – xxxii, M.S. ‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, 1872

[1] October 1915 No. 258-259 (A Progs.–Political), Government of India Home Department (N.A.I.)

[2] ‘अण्डज’ or those born from eggs, ‘स्वेदज’ or parasites, and those born of excreted waste (sweat, faeces, etc.) like microbes and worms, ‘उद्भिज्ज’ or vegetation, and ‘जरायुज’ or mammals

[3] “Near the city stand two considerable tombs of six and eleven yards in length respectively. The vulgar believe them to be the resting places of Seth and the prophet Job, and extraordinary tales are related of them.” (‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubārak)

Abu’l-Fazl does not seem to attribute much credulity to the popular claims about these tombs—the reason for which we will see at a later stage—yet speaks emphatically and at length about the city’s association with Rāma’s incarnation.

[4] “Some say that at Rattanpur is the tomb of Kabir the assertor of the unity of God. The portals of spiritual discernment were partly opened to him and he discarded the effete doctrines of his own time. Numerous verses in the Hindi language are still extant of him containing important theological truths.” (Ibid.)

[5] Sultan Muhammad-bin-Tughlaq is one of the exceptions who is known to have issued orders to have some temples of Hindus and Jainas restored and on an occasion got a monastery and a cow-shelter constructed, also for appointing Hindus to high offices and removing some of the restrictions imposed by sharī’at on non-Muslims. (‘Fatwā-ī-Jahāṅdārī’, Ziāuddin Baranī)

But these were more in the nature of occasional concessions made by individual rulers than part of formal policy change. We know definitely that the Jīzyāh continued to be exacted as also the pilgrimage tax and other inequitable impositions on Hindus. The land-tax on Hindu villages was raised to half of the produce which drove people to such desperation that entire villages gave up farming and escaped to forests and turned to robbing to make a living—with cruel punishments if caught—and led to many a famine. (‘Futūhat-ī-Firōz Shāhī’)

[6] There were examples now and then of a rare magnanimous Muslim ruler before him, like Zain-ul-Ābadīn (1424–60 C.E.) of Kashmīr—who similarly as Aḳbar banned cow-slaughter, rescinded jīzyāh and allowed the Brahmins to reconvert those Hindus who had been forcibly converted to Islam during the reign of his predecessor or who were otherwise willing to be reconverted—but the vision of pursuing this as a clearly articulated and comprehensive policy was definitely pioneering not only for a Muslim ruler but also in the entire Christian and the Islamic world where general and state persecution of those other than adherents of the dominant faith was par for the course. The Aḳbar Nāmā itself cites many cases of persecution of heretics, Shiās, Hindus and even those with unorthodox views, both before and during Aḳbar’s reign. Badā’unī (`Abd al-Qādir Badā’unī, 1540–1603 C.E.), referring to the period before 932 A.H. (1574-75 C.E.) tells us that it was customary to search out and kill heretics, let alone non-Muslims. Considering the prevailing Islamic rule and its precedent, Aḳbar’s task was therefore not an easy one.

[7] “At the present day, when owing to the blessing of abundant goodwill and graciousness of the Lord of the age [Aḳbar] those who belong to other religions have, like those of one mind and one religion, bound up the waist of devotion and service and exert themselves for the advancement of the dominion, how should those dissenters be classed with that old faction which cherished mortal enmity, and be the subject of contempt and slaughter.” (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’, Vol. II – Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubārak)

[8] This however was achieved over a period of about two decades, beginning 1562 C.E., before he was even twenty, as soon as Aḳbar could assert himself disengaging from the apron strings, so to speak, of what was famously termed the ‘petticoat government’, and with particular earnestness after 1593 C.E., the year he issued the order sanctioning reconversion of forcibly converted Muslims to Hinduism.

[9] Aḳbar’s supra-religious theory of kingship enunciated by Abu’l-Fazl on behalf of his sovereign in 1567, may be regarded as revolutionary in character inasmuch that it repealed the Islamic theory of sovereignty by laying down as one of the essentials, that “…on coming to the exalted dignity if he [a sovereign] does not inaugurate universal peace [religious toleration] and if he does not regard all classes of men, and all sects of religion, with the single eye of favour—and not be mother to some and be step-mother to others—he will not become fit for the exalted dignity.”

In August/September 1579, Aḳbar got a proclamation drawn up called ‘Mahzar’ and prevailed on the ulēmā to sign it, which authorised him to choose any one of the divergent views of the Muslim jurists on a controversial matter, religious or secular, and promulgate a law—in consonance with the Qur’ān—in the best interest of the state and the people. It enabled the emperor to brush aside the control exercised by the ulēmā on jurisprudence, and paved the way for the replacement of the sharī’at by what Abu’l-Fazl called the “divine will as manifested in the intuition of the emperor.”

After 1580, he did away with the office of the qāzī altogether and brought the judicial administration under secular courts (mīr-i ādl) presided over by the respective governor, the dīwān, the faujdār, the collector, the shiqdār (police chief) and the kōtwāl (local police officer), who decided cases on the basis of the common or customary law and equity. (It may be noted that most of Aḳbar’s provincial dīwāns were Hindus.)

[10] “In spite of the disapproval of statesmen, and of much chatter on the part of the ignorant, a sublime decree was issued. On account of deep-rooted enmity they [Aḳbar’s predecessors] were girded up for the contempt and destruction of opposite factions [non-Muslim religions and non-orthodox factions], but for political purposes and their own advantage, they fixed a sum of money as equivalent and gave to it the name of Jiyza.” (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’, Vol. II – Abu’l-Fazl)

Jīzyāh was reinstated in 1575, probably due to fiscal reasons, and then abolished again in 1579. The rescindment stayed in force until the time of Auraṇgzēb.

The measure was exceptional by all means and the ramifications for Hindus cannot be understated. In the sultanate period Jīzyāh was levied at a rough rate of annually Rupees 6 per adult. Considering that (in the Mughal period) the average monthly earning of a labourer was Rupees 8 monthly, it was a debilitating burden which led to mass conversions to Islam. This was added to the burden of tax on agricultural produce and commerce, which for Hindus was double the rate at which Muslims were taxed, in accordance with sharī’at. But what was worse that even this did not secure relief from the disabilities imposed by the Islamic state on Hindus’ lives, behaviour, dressing and activities. (As the chronicler Ziā-ud-Dīn Barani remarked, that Hindus should not be allowed religious freedom by simply paying a few taṇkās to the state treasury.)

[11] Abu’l-Fazl describes the incident and the view Aḳbar took in issuing the order when during an expedition to a hunting ground near Mathurā, it came to his notice that Hindus visiting the holy place—and other sacred spots of worship—had to pay a tax according to their wealth and rank, following from a longstanding law during Islamic rule:

“The Shāhinshāh in his wisdom and tolerance remitted all these taxes which amounted to crores. He looked upon such grasping of property as blameable and issued orders forbidding the levy thereof throughout his dominions. In former times, from the unworthiness of some, and from cupidity and bigotry, men showed such an evil desire towards the worshippers of God. H.M. often said that although the folly of a sect might be clear, yet as they had no conviction that they were on the wrong path, to demand money from them, and to put a stumbling-block in the way of what they had made a means of approach to the sublime threshold of Unity and considered as the worship of the Creator, was disapproved by the discriminating intellect and was a mark of not doing the will of God.” (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’, Vol. II – Abu’l-Fazl)

[12] 1) “…make prisoners of the wives and children and other relatives of the people of India, to enjoy them or sell them… no soldier of the victorious armies should in any part of his dominions act in this manner… and even if the combatants had to be made prisoners, still their families must be protected from the onslaught of the world-conquering [Mughal] armies. No soldier high or low, was to enslave them, was to permit them to go freely in their homes and relations.” (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’, Vol. II)

“Hindus who, when young, had from pressure become Musalmans, were allowed to go back to the faith of their fathers. No man should be interfered with on account of his religion, and every one should be allowed to change his religion, if he liked.” (‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, Vol. I)

2) After the conquest of Dhār when Aḳbar visited the city, an aggrieved woman brought a complaint against one of the victorious Mughal generals, Muhammad Hussein (a qurbēg of Abdullāh Ḳhāṅ) that he had violated her minor daughter and plundered her house. The offending commander was promptly seized and exemplary punishment inflicted on him. (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’ Vol. II, p. 226)

3) “The king has such a hatred of debauchery and adultery that neither influence nor entreaties, nor the great ransom, which was offered, would induce him to pardon his chief trade commissioner, who, although he was already married, had violently debauched a well-born brahman girl. The wretch was by the king’s orders remorselessly strangled.” – ‘Commentarius’ (Commentary of Father Antonio Monserrate), Anthony de Montserrat

Beveridge identifies the man with Jalā (Rūmī K. Ustad Jalābī of Ā’īn; called Jalābī or Ḥalābī Ćābuksawār in ‘Iqbālnāmā’ and described as the best horseman of the day) who was executed for rape, mentioned in ‘Aḳbar Nāmā’ III, p. 391-92 (“He was Akbar’s broker’s son and perhaps the son of Rumi Ḳhan, if not Rumi Ḳhan himself.”)

4) Camping at a place called Safēd Saṇg on Aḳbar’s march back from Kabul in November 1589, it was reported to him that “a base fellow had dishonoured a peasant’s daughter”. The offender was capitally punished and another culprit (Sharīf Khāṅ, the son of Mohammad `Abdu-ṣ-Ṣamad the calligrapher) who “had been in the plot with him” was also punished, as “a lesson to those who are apt to go astray.” (‘Aḳbar Nāmā’ Vol. III, p. 569)

Significantly, Sharīf Khāṅ was a close friend of Jahāṅgīr and became the Amīr-ul-Umarā under him, but the association did not save him. ‘Iqbālnāmā’, which corroborates the incident, narrates that “found to be the cause of the crime” he appears to have received corporeal punishment and was imprisoned.

[13] Instances of forcible conversion were heard of in spite of the imperial orders. E.g. in Sūrat, Christian prisoners were offered to be spared with their lives if they accepted Islam and upon their refusal executed by officials. In Daman, Portuguese prisoners were offered the choice between Islam and death. In 1604, a Portuguese was forcibly converted to Islam. But systematic conversion of non-Muslims to Islam was significantly stunted by these measures.

“The Muslims used their power with little tolerance. Throughout the journey from the coast to Fatehpur, for instance, the Fathers found that the Hindu temples had been destroyed by the Mohammedans (Agarenorum diligentia omnia idolorum delubra quae plurima erant dejecta). When war was in progress there was no pretence of mutual consideration; cows were freely slaughtered and infidels ‘sent to hell.’” – ‘Commentarius’, Anthony de Montserrat

[14] Aḳbar liberated all his own slaves with an imperial announcement on March 8, 1582. (Aḳbar Nāmā II) He outlawed bonded labour with an order of 1597 specifying 57 outlawed “unpraiseworthy practices” specifically in the context of artisanry and saffron-farming in Kashmīr. Though forms of bonded servitude seem to have continued, the proliferation of slavery that began with Islamic rule in the course of which large portions of defeated populations were turned into slaves, and sexual-abuse of minors, seem to have been checked.

It proved to be much harder though to wean the nobles off their fondness for catamites. In his third regnal year it came to Aḳbar’s notice, that a noble, Shāh Quli Ḳhāṅ Mahram, kept an adolescent boy called Qābul Ḳhāṅ to whom he was “passionately attached”. Severely disapproving of the practice, the Emperor had the boy forcibly removed from the noble’s possession. No punishment seems to have been meted though and the boy was restored by Bairam Ḳhāṅ to Mahram for gaining the latter’s loyalty.

In another incident in the eleventh year, Aḳbar similarly removed a boy kept by a prominent noble Jalāl Ḳhāṅ Qurchi. But the latter got him back and fled from the court. They were subsequently captured but Qurchi was restored to favour before the impending expedition to Siwānā. The practice was apparently so rampant among the nobility that it was seen as pragmatic to tolerate it.

[15] Dire conditions during famines forced many parents to sell their children or give them up to conditions of slavery. Famines were apparently not infrequent some of which are noted in the writings of contemporary chroniclers:

Gujarat, 1574 – 75 C.E. (“…people offered for sale a gently born (sharīf) [infant] for a cake of bread, but none would buy.” – Ārif Qandhārī)

Cambay, mid-1560s: “…have seene the men of the country that were Gentiles [Hindus] take their children, their sonnes and daughters” to sell “for eight or ten larins.” (Caesar Frederick)

Ralph Fitch records another famine in Cambay in the 1580s. The 1596-97 C.E. famine seems to have been widespread and Jesuit fathers found during this time in Kashmīr that many mothers “having no means of nourishing their children, exposed them for sale in the public places of the city.

This seems to have been the occasion for the institution of more descriptive laws formulated in more pragmatic terms. (“…if in times of acute hunger and distress, the parents have had to sell their children, then, when they recover the ability to do so, they may repay the amount and get their children freed from the yolk of slavery.” – ‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ II, `Abd al-Qādir Badā’unī) He notes (~1598), “Praise be to God, these days this practice [of selling children] has abated somewhat.”

In the year 1556-57 there was a severe famine in Delhi and the surrounding areas during which—by the testimony of Abu’l-Fazl and Badā’unī—people even took to cannibalism. These observations are however made in the context of proclaiming the beginning of a new era with Aḳbar’s reign and re-establishment of Islamic rule (“Apparently it was the pain of the past coming out in evidence so that by the blessings of the holy accession to the throne of the Caliphate, the inequalities of the time, and the crookedness of the world might all at once be removed”) and therefore could be coloured.

Famines continued to be a feature as much during Mughal rule caused to a great extent due to exaction of the agrarian surplus by Mughal mansabdārs.

Passages within Aḳbar Nāmā reveal that the imperial government typically responded by remitting taxes in the famine afflicted areas, appropriating and redistributing the excess stored by their officers and punishing them, and establishing kitchens in affected places.

“In this year [1596-97 C.E.] kitchens were established in every city. There was a deficiency of rain this year, and high prices threw a world into distress.”

“At this time some attention was paid to miscellaneous imposts. Fifty-five censurable customs were abolished. The husbandmen for a long time paid these, and until the order of remission took effect they did not believe in it [the abolition].”

“It also appeared [from investigations after a peasant revolt in 1597] that much evil had been caused by the tyranny of the fief-holders. In their ignorance of affairs they demanded the whole rent in money and sought for gold and silver from that country which was regulated by the division of crops. H.M. made remittances to crowds of men, and established choice regulations. The oppressors received their punishment. And kindness was shown to the injured cultivators. The whole country was divided into fourteen portions, and to each of these two bitikcīs (accountants), one an Indian and the other a Persian, were sent so that they might study the settlement-papers (ḳhām kāghaz) of every village and might ascertain the extent of the cultivated and uncultivated land, and of the collections, and might reckon one half of the produce as the share of the ruler, and return any excess.”

[16] “…no man or woman, minor or adult, was to be enslaved and that no concubine or slave of Indian birth was to be bought or sold, for this concerned priceless life.” (‘Tārīkh-i Aḳbarī’, Muhammad Ārif Qandhārī)

Merchants were ordered “not to take horses to, and bring slaves from Hindustan [territory east of the imperial capital then, Lahore]”

[17] 1) As late as 1595 C.E. we hear (in ‘Aḳbar Nāmā’ Vol. II) of enforcement measures to protect obedient [revenue-paying] villages from slave-collecting raids by “blind-hearted avaricious ones”.

2) Rafi’uddīn Ibrahīm Shirāzī in ‘Tazkiratu’l Muluk’ mentions that while travelling from Agra to Gujarat in 1563-64, one of his companions was found to have sold a slave in his possession. He was arrested by the kōtwāl and his ears were cut off and nailed on the walls of the fort as a warning to the others. The sale of slaves and concubines, he adds, had been forbidden as Aḳbar’s “brahman mistress” had told him that ‘his kingdom was losing nearly two lakh people each year due to slave trade.’ (Being a foreigner, Shirāzī was apparently unhappy at the stoppage of traffic of slaves from India westwards.)

[18] ‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ (Vol. II, p. 391) – `Abd al-Qādir Badā’unī;

‘Tazkīrā-i ‘Ulamā’-i Hind’ (Vol. II) – Rahmān ‘Ali;

‘Dabistān-i Mazāhib’ (“…a Hindu who, in his infancy, without his will, has been made a Muselman, if later he chooses to return to the faith of his fathers, is at liberty to do so, and is not to be prevented from it; also every person is permitted to profess whatever religion he chooses, and to pass, whenever he likes, from one religion’ to another.”)

[19] ‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ (Vol. II, p. 391) – Badā’unī

The right was extended to Christians by an order in 1603 C.E. (though oral permission seems to have been given earlier). – ‘Akbar and the Jesuits’, Pierre du Jarric (French Catholic missionary) However most of the converts the Christians gained were from among the dying, the destitute or the terminally ill. Du Jarric describing the persecution of the Fathers of the Third Mission speaks of Mohammedanism and Hinduism as the dominant (“strongly established”) religions.

[20] ‘Dabistān-i Mazāhib’ (“…if a Hindu woman, having fallen in love with a Muselman, wishes to adopt his religion, she can be taken by force and delivered up to her family. And likewise a Muselman woman, if she has fallen in love with a Hindu, and wishes to adopt his faith, is prevented from it, and not admitted in his caste.”);

‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’–II (“If a Hindū woman fell in love with a Musalman and entered the Muslim religion, she should be taken by force from her husband, and restored to her family.”);

‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’, Vol. I – Blochmann (“If a Hindu woman fell in love with a Muhammadan, and change her religion, she should be taken from him by force, and be given back to her family.”)

On one occasion, a Muslim by name Sayyid Mūsā, who wanted to marry a Hindu girl, had to elope with her and keep himself and the girl concealed for fear that the parents of the girl would be able to get her back by bringing up a claim and litigation. Though a son of one of the chief Sayyids of Kālpi, the girl’s family successfully got her back and Mūsā was imprisoned. After several unsuccessful attempts to be united with her, Mūsā pined away to his death. (‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ Vol. II, pp. 110-119) – Badā’unī

Though Aḳbar contracted marriages with Hindus to seal political alliances for what he saw as the larger good of his Empire, he was remarkably percipient in recognising the detrimental effect that indiscriminate mixing could have on the socio-religious fabric. The stipulations of Islam made inter-religious marriages unilaterally disadvantageous to non-Muslims resulting in stress between communities and he therefore outlawed such alliances resulting from acts of youthful passion that ran adversely into religious law.

Regrettably, such clarity is absent today, especially among Indian judicial authorities—though some countries do forbid these—leading to trends like ‘grooming gangs’ (commonly termed ‘love jihad’ in the present Indian context) creating havoc in societies.

The aspect of commingling was borne in mind even in poorhouses established by Aḳbar for maintaining destitutes by royal charity. Separate colonies were set up for Muslims (Ḳhairpurā) and Hindus (Dharmapurā), and an exclusive colony for Hindu mendicants called ‘Jōgipurā’.

“[On Dahserí, the ‘Ten Ser Tax’] H.M. takes from each big’hah of tilled land ten sers of grain as a royalty. Storehouses have been constructed in every district. They supply the animals belonging to the State with food, which is never bought in the bázárs. These stores prove at the same time of great use for the people; for poor cultivators may receive grain for sowing purposes, or people may buy cheap grain at the time of famines. But the stores are only used to supply necessities. They are also used for benevolent purposes; for His Majesty has established in his empire many houses for the poor, where indigent people may get something to eat.” (‘Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī’ 2/21)

[21] Badā’unī records these as an inhibition of Muslim rights. (To a hidebound mullā, putting Islam on the same footing as non-Islamic religions itself amounted to ‘persecution’.)

Sheikh Aḥmad al-Fārūqī al-Sirhindī (1564–1624 C.E.) wrote likewise in one of his letters to Farīd Buḳhārī: “The honour of Islam lies in insulting kufr and kafirs. One who respects the kafirs, dishonours the Muslims.”

Vincent A. Smith too wrongly attributes ‘persecution of Muslims’ with these measures, as Aḳbar treated Hindus and Muslims alike in this matter and such conversions to Hinduism were happening as well. Numerous such examples are cited in ‘Dabistān’ (Blochmann). Jahāṅgīr who discovered in his fifteenth regnal year that Hindus in Rajauri converted and married Muslims girls of the locality, issued orders to put an end to the practice and punish those guilty. The Tuzūk-ī-Jahāṅgīrī cites at least half-a-dozen cases of Hindus who married Muslim women or kept Muslim concubines, and converted these ladies to Hinduism, being punished (in one case with death.) However, in the absence of any incident being cited of the converse, it can be assumed that, unlike in Aḳbar’s reign, Jahāṅgīr did not as expeditiously punish Muslims who married Hindu women/ kept Hindu concubines.

[22] 1) ‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ II, Badā’unī

2) Du Jarric (‘Akbar and the Jesuits’)

3) Farmān dated Muharram 28, 999 A.H. (November 26, 1590 C.E.) addressed to Mubāriz-ud-Dīn Āzam Ḳhāṅ (the provincial governor) favouring Hīravijaya Sūrī Sēvḍa: “…it is ordered that no inhabitant of that city should interfere with them, nor should lodge in their temples or upāśrayas, nor insult them. Besides if any [of their temples or rest houses] have fallen down or become dilapidated, and if anyone among those respecting and liking him or desirous of giving in charity, desired to repair it or rebuild it, there should not be any restraint by any having superfluous knowledge or fanaticism.” It further directs Āzam Ḳhāṅ: “Haji Habibullah, who knows little of our quest for truth and realisation of God, has harmed this community, hence our pure mind manages the world, has been afflicted with pain, so you should remain so watchful over riyāsat that no one can persecute anyone.”

4) A similarly worded farmān dated Safar 25, 1010 A.H. (August 14, 1601 C.E.) in favour of Vijayasēna Sūrī, directed to imperial officers in Gujarat and Saurāśtra, prohibited slaughter of animals during the prescribed six months in the year, asked them to show respect to the petitioner and prevent Muslims from obstructing the rebuilding and renovation of their temples. This order carrying the nishān of prince Salīm, was a confirmation of the earlier farmān and carried a categorical note that “strict warning be given that the same be executed in the best manner and none should pass any order contrary to the same.”

[23] “The killing of animals on the first day of the week was strictly prohibited because this day is sacred to the Sun, also during the first eighteen days of the month of Farwardín [Persian: first month of the Solar Hijrī calendar]; the whole of the month of Ábán, the month in which His Majesty was born; and on several other days, to please the Hindús. This order was extended over the whole realm and punishment was inflicted on everyone, who acted against the command. Many a family was ruined.” (‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’, II – Badā’unī)

[24] This was implemented so stringently that in 1612 C.E. when Eid-uz-Zuha (Bakrīd) fell on a Thursday, slaughter was disallowed by Jahāṅgīr and the Muslims were obliged to perform ritual slaughter on the next day. It is important to note however that Jahāṅgīr attempted to explain the continuation of the prohibition along the lines of the self-denying Sūfī ordinance forbidding meat.

[25] 1) “He prohibited the slaughter of cows, and the eating of their flesh, because the Hindus devoutly worship them, and esteem their dung as pure.”

“Another (order) was the prohibition to eat beef ”, Badā’unī notes darkly. “The origin of this embargo was this,” he narrates, “that from his tender years onwards, the emperor had been much in company with rascally Hindus, and thence a reverence for the cow (which in their opinion is the cause of the stability of the world) became firmly fixed in his mind.” He informs that “[Aḳbar] had introduced a whole host of the daughters of the eminent Hindu rajas into his harem, and they had influenced his mind against the eating of beef and garlic and onions, and association with people who wore beards—and such things he then avoided and still does avoid.” (‘Muntakhāb-ut-Tawārīkh II’, Badā’unī) He mentions that in 1590-91, Aḳbar had forbidden eating the meat of oxen, buffaloes, goats or sheep, horses or camels. For some time in 1592, during his visit to Kashmīr, even fishing was prohibited.

2) The Islamic purist Sheikh Aḥmad Sirhindī pleaded with Jahāṅgīr (to no avail) for the re-imposition of jīzyāh and the abolition of the ban on cow slaughter. – ‘Maktubat-i Rabbān’ (Letters of Sheikh Aḥmad al-Fārūqī al-Sirhindī, No. 81)

3) “…the emperor [Aḳbar] forbade his subjects to kill cows and to eat their flesh; … The Hindus say also that, as many advantages are derived from the cow, it is not right to kill it. The Yezdánian maintained that it is tyranny to kill harmless animals…” (‘Dabistān-i Mazāhib’)

4) Aquaviva’s letter dated September 27, 1582, complaining that the Jesuits could not get meat on Sundays owing to the ban. (‘The Jesuits and the Great Mogul’, Sir Edward Maclagan)

5) “People were condemned to death for killing cows. Whatever the King’s actual faith was, it was not Islam. He was a Gentile [Hindu]. He followed the tenets of the Verteas [Jainas]. He worshipped the Sun like the Pārsīs. He was the founder of a new sect (secta pestilens et perniciosa) and wished to obtain the name of a prophet [sic.]” (Letters of the Third Jesuit Mission, ‘The Jesuits and the Great Mogul’ – Edward Maclagan)

6) “Vijayasena, who was called by Akabbara to Ludhapur, received from him great honours, and a phuraman, forbidding men to slaughter cows, bulls and buffalo-cows, to confiscate the property of deceased persons and to make captives in war; who, honoured by the king, the son of Choli Vegama [Hamīdā Bānu Bēġûm], adorned Gujarat.” (‘Commentarius’, Anthony de Montserrat)

[26] 1) ‘Badaoni and the Religious Views of Akbar’, Heinrich F. Blochman (A.S.B. Progs, March 1869)

In his Persian account Badā’unī writes that “Hindus kill good men if they kill cows”.

2) ‘Akbar, the Great Mughal’ (Vincent A. Smith)

3) “…the last Qaran (age) or so, the kafirs were not satisfied with the mere promulgation of the practice of the kufr but they even desired total abolition of Islamic pactices and complete annihilation of all traces of Muslims and Islam in India; the things had reached such a pass that if the Muslims practised the Islamic rites [said in the context of cow slaughter] they were beheaded.” (Sheikh Aḥmad Sirhindī, writing on Aḳbar’s reign)

[27] Badā’unī claims that Muslims suffered “great oppression” (were killed and their properties confiscated) on account of the prohibition of cow-slaughter and slaughter on illegal days. A well-known Muslim divine of Thānēsar, and an eminent scholar who had been employed in the translation of the Mahābhārata, was exiled to Bhakkar on account of charges of slaughtering a cow brought against him by Hindus. (Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh III, p. 118) By all means the externment was an ignominious circumstance as social undesirables and religious charlatans usually got banished to Bhakkar and Qandhār, exchanged for colts (e.g. leaders of the Ilāhī sect).

A specific case is known from Pûṇjāb, from the records of Jesuit missionaries (Letters of Fr. Emmanuel Pinheiro) when they had to use their influence with the governor of Lāhōre to secure the release of a Chaldaean Christian sentenced to death for killing a cow. (‘Akbar the Great’, Vol. 1 – A. L. Srivastava)

[28] In all the number of prohibition days amounted to about six months (in Gujarāt).

[29] Sheikh Aḥmad Sirhindī writes: “In previous Qarans the kafirs, enjoying complete political ascendency, promulgated the ordinances of kufr in the abode of Islam and the Muslims could not put the ordinances of Islam into practice. If they attempted to do so, they were done to death. Alas! Alas! The believers in Muhammad, the Prophet of God and beloved of the world, lived in ignominy and disgrace and those who did not believe in him were held in trust and respect. Muslims with a wounded heart lamented over this sad plight of Islam and their enemies mocked and jeered at them and thus sprinkled salt over their wounds.”

[30] Mullā Shāh Aḥmad (‘Maktūbāt-i Mullā Aḥmad’–II) agonises over the Emperor’s inaction saying that ‘Islam had become so weak that Hindus were destroying mosques without fear.’ (He however cites this singular instance to substantiate his gripe.) It may at the least be inferred that the government was lax in checking these activities. But it is clear that Hindus during Aḳbar’s reign felt confident enough to assert their rights, wrest back their sacred spaces and even demolish mosques. Non-Muslims could openly discuss and be critical of Islam (being enheartened by frank discussions in the Emperor’s presence.)

[31] “When Akbar left Lahore and reached Butala he came to know that a fight had taken place between Musalman Fakirs and Sannyasis. He went to the spot and put to prison the Musalman fakirs who had done injustice, and had broken some of the temples. He ordered the temples to be repaired and from there he crossed the Bias and visited the house of Guru Arjan, a disciple and successor of Baba Nanak, and he was very much pleased when he recited some of the poems of Baba Nanak about the unity of God-head. The Guru expressed his obligation to the Emperor for his visit and at the time of his departure represented to him that in the Panjab the price had gone up to this extent that the people found it difficult to pay the revenue. The Emperor accepted his request and issued orders to his officers to reduce the revenue by one tenth or one-twelvth.” (Khulāsat-ut-Tawārīḳh (Persian), p. 262)

[32] It is however not possible to verify this statement failing any surviving record to substantiate it.

[33] This order was renewed with the farmān of Muhammad Shah dated July 8, 1723: “…This insignificant writer, who is a native of the holy place which is the maulud of Rama is reducing it in writing with pen. By order, it is certified that six bighas of land in the province of Oudh which was granted for the construction of Hanuman Tila, is given to Abhayarama after comparing it with the deed issued on the 13th Ramzan of 1008 A.H.”

Interesting is the use of the word ‘maulūd’ (place of birth) for Ayōdhyā and the scribe’s evident pride at belonging to the place, a clear indication that there was no ambiguity in the minds of Hindus and Muslims in the Mughal period about the status of the city as a holy place of immense significance for being the birthplace of Rāma.

[34] The Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī names several Hindu divines and learned men, among them saints of the Rāmānaṇdī sect, Rāmtīrtha, Nara Siṇgh, Rām Bhadra and Rāma Kishna. The divines are categorised according to their niveau, the first, those who perceived “the mysteries of the external and the internal, and in their understanding and the breadth of their views, fully comprehend both realms of thought, and acknowledge to have received their spiritual power from the throne of his Majesty [here: God]”, which included saints like Rāmtīrtha and Nara Siṇgh. The other category of sādhūs were said to have paid “less attention to the external world; but in the light of their hearts they acquire vast knowledge”, under it names like Rām Bhadra, and those like Rāma Kishna in a third category. The purpose of categorisation was most likely to determine eligibility for receiving state grants and therefore very likely that the Hanumān Ṭīlā grant in Ayōdhyā was made in favour of either Nara Siṇgh or Rāmtīrtha. Nothing is known about Rāmtīrtha, but Nara Siṇgh named in Ā’īn is likely the same as Nara Siṁha (Naraharidāsa), the preceptor of Tulasīdāsa. (Why Tulasīdāsa finds no mention in the Ā’īn is probably because at the time it was compiled the saint had still not gained in renown.) Tulasīdāsa is said to have been an elderly person by the time he completed the composition of the Rāmaćaritamānasa and presuming Nara Siṇgh was his guru, the likelihood of his being alive in 1600 is very slim. Based on this Kishore Kunal estimates that Rāmtīrtha was the recipient of the said grant.

[35] 1) “Raja Man Singh built a temple at Banaras. He spent 8 to 10 lacs of rupees from my father’s treasury. The Hindus have great faith in the temple and they have this belief that those who die here go straight to heaven—no matter whether they are cats, dogs or men. I sent a reliable man to enquire everything about the temple and he reported that the Raja spent one lac rupees of his own in the construction of the temple. At this time, there is no other bigger temple than this. I enquired from my father as to why he had approved of the construction of the temple. He replied: I am the Emperor and the Emperors are the shadow of God on earth. I should be bountiful to all…” Jahāṅgīr further states: “I ordered a bigger temple to be constructed near it.” (Tuzūk-ī-Jahāṅgīrī)

2) “Raja Man Singh built a big temple at Banaras for the worship of the people.” (Jaipur Vaṇśāvalī)

3) The temple is also referred to in the memoirs of Abd’l Latīf, a cultured Muslim traveller, compiled early in the reign of Jahāṅgīr, which describes the architectural beauty of this temple wishing very much that it had been built in the service of Islam rather than Hinduism. (S. R. Sharma, Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol. XIII, 1937)

By another version, Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa, son of Rāmēśvara Bhaṭṭa, rebuilt on a grand scale the temple of Viśwanātha which had previously been demolished by the Muslims. As per the tradition in ‘Vyavahāra Mayūkha’: “Once the country had been experiencing serious drought. Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa prayed for rains. According to his forecast, the rains came to the delight of all. So he was able to secure the necessary permission from the local Muslim authority to reconstruct the temple of Viśwanātha.” This narration is reiterated in a 17th century literary work (Catalogue of Sanskrit MSS of India Office, I) by Divākara Bhaṭṭa (the daughter’s son of Śaṇkara Bhatta, son of Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa) that “the great Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa, son of Rāmēśvara, established the Viśwēśvara Temple.”

Yet another tradition prevalent in Bênāras narrates that Ṭōḋar Mal had invited Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa to the Śrādha ceremony of his father (attested by the Sanskrit work ‘Gadhivaṃśavarñanaṁ’.) He is said to have obtained a vision of his ancestors by Nārāyaña Bhaṭṭa’s grace and out of reverence for the preceptor caused the Viśwanātha temple to be built by providing necessary funds and resources.

It is not possible to say with certainty which of the temples built by Rājā Mān Siṇgh and Ṭōḋar Mal respectively, was the one built on the site of the ancient Viśwēśvara temple in Bênāras, since the temple is non-existent at present and the location of the temple built by Mān Siṇgh is uncertain. It is also not possible to identify which “bigger temple” near Mān Siṇgh’s temple was built by Jahāṅgīr. Irrespective of the agency however, the restoration of the holy site would not be possible without state approval and likely funded by the Mughal treasury as well. Ironically, it was destroyed by the same Mughal state in less than 8 decades, as per ‘Ma’āsir-ī-Ālamgīrī’, in September 1669 C.E.

According to one theory, the temple built by Mān Siṇgh is identifiable with a building called ‘Maan Mandir’ (Temple of Mān) situated on the bank of the Ganges just a few yards to the west of Daśaswamēdha Ghāt at Vārāñasi. But the preeminence of the temple built by Mān Siṇgh as described in Jahāṅgīrnāma makes this an unlikely supposition. The story that the Hindus boycotted the temple built by the Ambēr ruler on account of the fact that the family had married a daughter to the Mughal emperor also seems to be a latter-day confabulation. According to ‘The Plan of the Ancient Temple of Vishveshvur’ drawn by James Pincep (1832 C.E.) the temple built—according to common lore by Ṭōḋar Mal—was to the west of the present Viśwanātha temple (built by the Hōlkar ruler, Ahalyābāī, 1780 C.E.) Between these two lies the famous Jnāna-Vāpi maṇḋapa.

[36] The temples of Gōpinātha, Rādhā Ballabha, Nandnaṇdana, ‘Gōbinda Rāi’ (Gōvinda Dēva), Madana Mōhana, Gōvardhana, Hari Gōpāla Rāi. [Collection of Madan Mohan Temple—Vrindavan Research Institute (now with N.A.I.) – ‘Akbar and the Temples of Mathura and its Environs’, by Tarapada Mukherjee and Irfan Habib (Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Vol. 48, 1987)]

[37] Aḳbar’s farmān dated Jumada 5, 972 A.H. (January 8, 1565 C.E.) to Gōpāla Dāsa, servant of Madana Mōhana temple, assigned 200 bīghās of land as inām (tax-free grant). (A later farmān in favour of the Gōvinda Dēva temple provides in the zimm (reverse) a list confirming all previous grants to servants/priests of the seven temples conferred through four farmāns including this grant of 1565 C.E.*)

Another grant of 100 bīghās was made in favour of the Madana Mōhana Temple in Rabi 992 A.H. (April-May 1584 C.E.) by Rājā Ṭōḋar Mal, which was affirmed by an imperial order from Jahāṅgīr in 1613, in favour of one Śrīćaṇda, sēvak of dēvala Madana Mōhana.

Interestingly, the Madana Mōhana and Gōvinda Dēva temples belonged to the Ćaitnya sect, the adhikāra (management) of which in Aḳbar’s time rested solely with āćārya Jīva Gōswāmi, whose library listed a manuscript of Ayōdhyā-mahātmya which we read about previously. His right to the management of the temples and to claim all offerings (ḳhairāt) made there was protected by an imperial order issued Rabi 14, 976 A.H. (October 6, 1568 C.E.)

Among the several small and big grants made by the emperor and subordinate Mughal officers (like Rājā Bihārī Mal, Rājā Bīrbal, and many others) are those of villages and cultivable lands for revenue to maintain respective temples, tax-free grazing lands for cows and oxen belonging to temples (1581 C.E. imperial farmān of queen mother Hamīdā Bānu Bēġûm and another grant by Abd’r Rahīm Ḳhāṅ-i-Ḳhanaṅ of 1588 C.E.), and an order (1593 C.E. by Aḳbar) prohibiting animal slaughter and hunting of peacocks in the pargañās of Mathurā, Sahār Mangōttā and Ao, to safeguard the sanctity of the holy cities and the surrounding areas.

The ban was not a nominal expression of goodwill but a stringent law and remained in effect in the time of Jahāṅgīr as we know of a definite case from 1628, when a Muslim in Burdwan was arrested by the shiqdār for killing a peacock. The punishment it attracted was whipping and amputation of the right hand. Fr. Manrique tells us that in his defence he had offered that the man acted in accordance with his own faith (Islam) but the plea for leniency was rejected. (‘Travels of Fray Sebastien Manrique 1629-1643’)

It is indeed ironical that these munificent state concessions and rights the Hindus do not have in supposedly ‘independent’ India today!

*A farmān dated 1598 C.E. records a grant of ~600 acres made to 35 temples in Vṛndāvana, Naṇdagrām, Gōvardhana and Mathurā. The order redistributed previously granted land of total 504 bīghās among the 7 temples in Mathurā-Vṛndāvana, and conferred an additional 500 bīghās ilāhī of land among 28 other temples. The distinctive element of this order is that for the first time the grants were made to the temples as institutions instead of certain named temple servants and were for perpetuity. (Ibid.)

One of these 28 temples was the Kēśava Rāi temple of Mathurā, granted 45 bīghās with this deed, which was famously destroyed during the reign of emperor Auraṇgzēb.

[38] Equivalent to 15 Rupees

[39] One of these gold coins is presently in the possession of the British Museum of London and the other with the Cabinet de France at Paris. The silver coin is preserved at Bharat Kala Bhavan at Vārāñasi.

[40] How far he succeeded in his aims is debatable. The disparaging observations of Badā’unī, the translator of Rāmāyaña, on the text he was tasked to translate and the beliefs of Hindus, betray the characteristic virulence of a bigoted mullā towards non-Muslims.

On the Mahābhārata, which the Emperor assigned him to translate, Badā’unī finds only “puerile absurdities of which the 18,000 creations may well be amazed…but such is my fate, to be employed on such works.”

[41] “Philologists are constantly engaged in translating Hindi, Greek, Arabic, and Persian books, into other languages. Thus a part of the Zích i Jadíd i Mírzáí (vide IIIrd book, A’ín I) was translated under the superintendence of Amír Fathullah of Shíráz (vide p. 33), and also the Kishnjóshí, the Gangádhar, the Mohesh Mahánand, from Hindí (Sanscrit) into Persian, according to the interpretation of the author of this book. The Mahábhárat which belongs to the ancient books of Hindústán has likewise been translated, from Hindi into Persian, under the superintendence of Naqíb Ḳhán, Mauláná ’Abdul Qádir of Badáon, and Shaikh Sultán of T’hanésar.” (Blochmann)

[42] In case of public law, though Aḳbar made modifications in the Islamic law, it was accompanied by a declaration by the state that it would not prosecute offenders—mostly non-Muslims—against certain laws. Criminal law continued to be Islamic for both, however without being prejudicial against non-Muslims.

Again, the impact of these concessions to empower Hindus cannot be underestimated. A minor change made in the Hindu inheritance law by Shāh Jahāṅ later brings this home sharply, by which he prevented converts to Islam from being disinherited from ancestral property. This was not allowed under the prevalent Hindu law and stripped Hindus of this protection against proselytisation that they had in the reigns of Aḳbar and Jahāṅgīr. (‘The Religious Policy of the Mughal Emperors’, S. R. Sharma)

[43] “Another [new ‘customs’ introduced by Aḳbar] was that a learned Brāhman should decide the case of Hindūs, and not a Qāzi of the Musalmāns.” (‘Muntakhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ Vol. II, p. 356) – Badā’unī

[44] “His majesty Nuruddin Mohammad Jahangir appointed Sri Kanta [a Brahmin from Kashmīr] to the office of the Qazi of the Hindus so that they might be at ease and be in no need to seek favour from a Muslim.” – (‘Dabistān-i Mazāhib’)

[45] 1) “Today, when the happy tidings of the downfall of the one who was prohibiting Islam [i.e. death of Aḳbar] and the accession of the king of Islam [Jahāṅgīr], have reached the ears of every high and low, the Muslims have considered it obligatory to help and assist the king and guide him to promulgate the laws of Shariat and strengthen the faith. This support and furtherance can be achieved either by words or deeds. The highest form of help is to explain the problems of the Holy Law and the manifestation of the beliefs based on Kalam in accordance with the Quran, the Sunna and the consensus of the community lest some innovator [alluding to Aḳbar] or prevaricator may mislead the people and make the matters worse and confounded.” (Sheikh Aḥmad al-Fārūqī al-Sirhindī at Aḳbar’s death in 1605, in a letter to his disciple and friend Farīd Buḳhāri)

2) “The Prophet’s Law [Shari‘at-i Nawābī] which had withered like a red flower by the winter wind, obtained renewal at the accession of the king of Islam and mosques, hospices and madarsas which of thirty years had become the homes of beasts and birds, and from which no calls for prayer were heard by anyone, [became] clean and cleansed, and the Prophetic call to prayer reached the sky; moreover all directions and prohibitions and the Rules of Islam as current among the people are enforced.” (‘Tawārīkh-ī-Ḳhāṅ Jahāṅī’, by Nimatullāh al-Harāwī – 1613 C.E.)

3) “He used to wear the Hindu mark on his forehead … Mosques and prayer-rooms were changed into store-rooms and into Hindu guard-rooms.” (‘Muntaḳhāb-ut-Tawārīkh’ Vol. II, p. 322)

4) The third Jesuit mission found several mosques in a state of ruination since they had not been repaired. (“…in the city there is no mosque and no copy of the Qur’ān [sic.] The mosques previously erected have been turned into stables and public granaries.” – Pinheiro’s letter dated September 3, 1595 – Maclagan, 70)

5) “At the instigation of some mischievous persons, my father has abolished the arrangements for the maintenance of Ḳhātib, the mu’azzin and imām in the mosques and has prohibited the performance of namāz in congregation. He has converted many of the mosques into storehouses and stables. It was improper of him to have acted in this manner. They [the recipients of the farmān] should resume the paying of stipends for the maintenance of the mosques, the ḳhātib, the mu’azzin and imām , and should induce people to offer prayers. Anyone showing slackness in this respect would be duly punished. (Jahāṅgīr’s farmān to local hākims issued 1601 C.E. during his rebellion – quoted in ‘Tazkiratu’l Muluk’, Rafi’uddīn Ibrahīm Shirāzī)

6) Through Mughal records it is possible to establish that Aḳbar had adopted a restrictive attitude towards practitioners of orthodox Islam. A series of orders/instructions from year 1595, in response to requests and queries of prince Sultan Murād, posted in Deccan at that time, we come to know of a stricture on openly offering namāz in conformity with orthodox Islamic prescription. The letter seeks advice on how to deal with those in the camp performing prayers in the manner imitating theologians (fuqhā-i taqlid Sha’ār). Aḳbar’s response suggests that such people should receive an admonition (nasīhat) to return to the path of reason (rāh-i ‘aql), however warned against coercing people against their will in accordance with the policy of ‘sulh-i kul’. The measure, presumably to contain irrational, obdurate behaviour, appears to have been short-lived, but enough to evoke the indignance of the Muslim orthodoxy.

[46] From administrative and financial records it is apparent that several Muslim scholars, theologians, teachers and saints received grants from the state. However, it was greatly curtailed and no longer limited to luminaries of Islam alone. Likewise, official religious celebrations too were not kept exclusive to the Muslim faith. On occasions, though rarely, Aḳbar did lead Islamic public prayers. Equally he made Śivarātrī an occasion to assemble yōgīs from all over the empire to listen to discourses and discussions on Hindu beliefs and practices. Abu’l-Fazl mentions in Ā’īn-i Aḳbarī that Aḳbar “occasionally” joined namāz “to hush the slandering tongues of the bigots of the present age.” It is however clear that he had long ceased to follow it as a personal faith.

[47] The Aḳbar Nāmā expounds in detail Aḳbar’s theory of kingship conveying his grandiloquent self-image as a divinely ordained ruler over men which was closely linked with the idea of universal sovereignty. It however diverged radically from the Islamic theory of sovereignty which was vested in the sole authority of the ḳhalīfā. While this idea made it an impossibility to admit, in Aḳbar’s mind, the autonomous authority of another mortal in what he considered to be his realm, it also evoked in him the sentiment of a just, benevolent despot who looked upon all his subjects as a father towards his children, irrespective of their religious beliefs.

The only other Muslim rulers before Aḳbar to have formally negated the authority of the ḳhalīfā were Ghīyās-ud-dīn Balban (1265-87 C.E.) and Qutb-ud-dīn Mubārak Shāh Khiljī (1316-20 C.E.) who—formally—assumed the prerogative of the ḳhalīfā by taking on the title ‘zillillāh’ or ‘zilli Allāh’, meaning ‘shadow of God’ (or vice-regent of God) and getting the ḳhutbā read in their own name. However both these predecessors entertained no feeling of magnanimity towards the Hindus.

[48] “…having on one occasion asked my father the reason why he had forbidden anyone to prevent or interfere with the building of these haunts of idolatry, his reply was in the following terms: ‘My dear child,’ said he, ‘I find myself a puissant monarch, the shadow of God upon earth. I have seen that he bestows the blessings of his gracious providence upon all his creatures without distinction. Ill should I discharge the duties of my exalted station, were I to withhold my compassion and indulgence from any of those entrusted to my charge. With all of the human race, with all of God’s creatures, I am at peace; why then should I permit myself, under any consideration, to be the cause of molestation or aggression to anyone? Besides, are not five parts in six of mankind either Hindus or aliens to the faith; and were I to be governed by motives of the kind suggested in your inquiry, what alternative can I have but to put them all to death! I have thought it therefore my wisest plan to let these men alone. Neither is it to be forgotten, that the class of whom we are speaking, in common with the other inhabitants of Agrah, are usefully engaged, either in the pursuits of science or the arts, or of improvements for the benefit of mankind, and have in numerous instances arrived at the highest distinctions in the state, there being, indeed, to be found in this city men of every description, and of every religion on the face of the earth.” (Tuzūk-ī-Jahāṅgīrī)