By Smita Mukerji

The primary purpose of history is to gain learning. The events, occurrences and personalities of our past provide the backdrop against which we determine our choices for today and course for the future, both collective and individual. This is premised upon the uncompromisable principle that history be correctly told. Distortion of Indian history, first according to the imperialist prescript and later along the lines of Marxist and secular-liberal ideological scheme, has severely handicapped Indians in building a meaningful view of our past. The ideological sway of the Marxists in academic and media circles first came to be challenged with the growth of social media in the past decade or so which has grown into something of a movement in the last 6 to 7 years. But this build-up has its pitfalls, mainly that opinions, often rude and uninformed, are handed around as authorities.

A million motivations crisscross the social media landscape and views align and diverge according to personal biases people seek to have confirmed. But as much as it provides a platform to publish one’s views freely without being obstructed by a coterie, the noisy e-interaction world is not really the ideal place for establishing evidence-based, academically sound truth.

Recently, some Facebook pages and twitter handles have sprung up which claim to bring out the ‘real past’ by blasting the previously established narrative. But the contents put out are unreliable claims, often those that appeal to the basest prejudices, the lowest denominator in taste. One such source is an anonymous handle that goes by the nick ‘True Indology’, which regularly churns out snippets from sundry sources with claims mostly fashioned as exposés of historical personalities. The handle is supported by several tens of thousands of followers and bot accounts which ensures that any sensible discourse is drowned out by offensive, abusive trolling at any challenge to the ‘facts’ trotted out by this handle, an online enactment of mob-lynching.

One recent set of tweets from this handle claimed that the Mughal Emperor Akbar invaded the Jwalamukhi temple in Kangra (present-day Himachal Pradesh).

To restore the ‘facts’ to this hopeless garble of half-truths and fable peddled by the ‘True Indology’ handle as ‘history’:

- First and foremost, the temple talked about in Muntakhab ut-Tawarikh of Bada’uni is not the Jwalamukhi temple, but the Mahamaya or ‘Mahamai’ (sic.) temple in Bhavan or the ‘fortress of Bhun’ (sic.) as mentioned in contemporary records, which is about 2 miles from the Kangra fort. Jwalamukhi temple is on the way to Nagarkot ~35 kms away from this place!

Bada’uni’s account is confirmed in almost precise terms in Tabakat-i-Akbari of Khwaja Nizam-ad-Din Ahmad.

The region and its temples find mention in contemporary European accounts too, the first of these by the English traveller William Finch (though he does not seem to have personally visited the place) contained in Purchas’s Pilgrimes, 1611 C.E.:

“Bordering to him is another great Rajaw, called Tulluck Chand, whose chiefe city is Negarcoat, 80-c. from Lahore, and as much from Syrinan,[1] in which city is a famous Pagood, called Je or Durga unto which worlds of people resort out of all parts of India. It is a small short idol of stone[2], cut in forme of a man; much is consumed in offerings to him, in which some also are reported to cut off a piece of their tongue, and throwing it at the Idol’s feet, have found it whole the next day, (able to lye I am afraid, to serve the father of lyes and lyers, however); yea, some out of impious piety here sacrifice themselves, cutting their throats and presently recovering; the holyer the man, the sooner forsooth he is healed, some (more grievous sinners) remaining half a day in pains before the Divell will attend their cure. Hither they resort to crave children, to enquire of money hidden by their parents or lost by themselves, which, having made their offerings, by dreams in the night receive answers, not departing discontented. They report this Pagan Diety to have been a woman, (if a holy Virgin may have that name), yea, that she still lives, (the Divell shee doth); but will not shew her selfe. Divers Moores also resort to this Peer. This Rajaw is powerful, by his Mountains situation secure, not once vouchsafing to visit She Selim.”

Possibly the earliest European visitor to Kangra was an Englishman Thomas Coryat, and on the authority of his writings Terry, the Chaplain of Sir Thomas Roe, wrote of the place 1615 C.E.:

“Nagarcot, the chiefe city so called, in which there is a Chapel most richly set forth being ceiled and paved with plates of pure silver, most curiously imbossed overhead in several figures, which they keep exceeding bright, by often rubbing and burnishing it, and all this cost these poor seduced Indians are at, to do honour to an idol they keep in that Chapel… The idol thus kept in that richly adorned Chapel, they called Matta, and it is continually visited by those poor blinded Infidels, who out of the officiousness of their devotion, cut off some part of their tongues to offer unto it as sacrifice, which (they say) grow out again as before…”

In reference to Jwalamukhi temple he writes:

“In this province likewise there is another famous pilgrimage to a place called Jallarmakee [Jwalamukhi] where out of cold springs, that issue out from amongst hard rocks, are daily to be seen continued eruptions of fire, before which the idolatrous people fall down and worship. Both these places were seen and strictly observed by Mr. Coryat.”

In another historical reference to the place the French traveller, Jean de Thévenot, writes in 1666 C.E.:

“They are pagodas of great reputation in Ayoud, the one at Nagarcot and the other at Calamac [Jwalamukhi], but that of Nagarcot is far more famous than the other, because of the idol, Matta, to which it is dedicated, and they say that there are some Gentiles that come not out of that pagod without sacrificing part of their body. The devotion which the Gentiles make show of at the pagod of Calamac, proceeds from this, that they look upon it as a great miracle that the water of the town, which is very cold, springs out of rook of Calamac, is of the mountain of Balagrate (Balaghat), and the Brahmans who govern the pagod make great profit of it.”

Abu’l Fazl, the official biographer of the Mughal emperor Akbar writes:

“Nagarkot is a city situated upon a mountain with a fort called Kangra. In the vicinity of this city upon a lofty mountain is a place, Maha Maiy, which they consider as one of the works of the divinity, and come in pilgrimage to it from great distances, thereby obtaining the accomplishment of their wishes. It is most wonderful that in order to effect this they cut out their tongues, which grow again in the course of two or three days, and sometimes in a few hours.” …

“According to the Hindu mythology Maha Maiy was the wife, but the learned of this religion understand by this word the power of Mahadeva, and say that she, upon beholding vice, killed herself, and that different parts of her body fell on four places. That the head with some of the limbs alighted on the northern mountains of Kashmir, near Kamraj, and which place is called Sardha. That some other members fell near Bijapur in the Dakhan, at a place called Talja Bhawani. That others dropped in the east, near Kamrup, and which place is called Kamcha, and that the rest remained at Jalandhar on the spot above described.”

It can be seen that European accounts of the temples and the devotions practiced by people there are much more condescending in tenor than the descriptions in Muslim sources who regard it more with wonderment and awe.

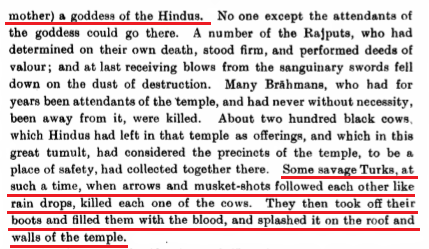

The question is, were temples desecrated or destroyed in Akbar’s time? Of course, they were! These are mentioned within Akbar Nama itself. The Mughal army was comprised for the greater part of Central Asian recruits, mostly rabid Islamists who would never let an opportunity pass to unleash Islamic bigotry on kafir people and temples. But this was clearly not Akbar’s state policy. The siege referred to in Bada’uni’s account was from 1572 C.E. and as Akbar consolidated his empire having subdued most of the revolts, he increasingly came down hard on the bigoted elements in his nobility.[3]

The question is, were temples desecrated or destroyed in Akbar’s time? Of course, they were! These are mentioned within Akbar Nama itself. The Mughal army was comprised for the greater part of Central Asian recruits, mostly rabid Islamists who would never let an opportunity pass to unleash Islamic bigotry on kafir people and temples. But this was clearly not Akbar’s state policy. The siege referred to in Bada’uni’s account was from 1572 C.E. and as Akbar consolidated his empire having subdued most of the revolts, he increasingly came down hard on the bigoted elements in his nobility.[3]  Most importantly, he provided an even playing field by allowing Hindus to rebuild destroyed temples, at times to even demolish standing mosques on them without the state acting against them. (This is lamented at length in Islamic records!) This was unprecedented in the history of Islam in India and indeed in the history of any part of the world where Islam spread.

Most importantly, he provided an even playing field by allowing Hindus to rebuild destroyed temples, at times to even demolish standing mosques on them without the state acting against them. (This is lamented at length in Islamic records!) This was unprecedented in the history of Islam in India and indeed in the history of any part of the world where Islam spread.

- Akbar personally never visited Nagarkot! Not on this instance, nor later. The temple was apparently restored, after Todar Mal was given the charge of turning the annexed country into an imperial demesne[4], because in March 1582 when Akbar visited the area he expressed a wish to visit the temple. But his idea was clearly not irreverence!

“Akbar was marching towards the Indus, he went to see the wonders of the temple of Nagarkot, which has from old time been a place of pilgrimage. … When Akbar halted for the night at the town of Desūha, which was in Rajah Bīr Bar’s fief, the spiritual form, of which strange stories are told, appeared to him in a dream. She rehearsed the greatness of the emperor, but warned him against his intention. In the morning he related his dream and turned back.” ~ Ma’asir ul-Umara

“When he heard of the wonders of that ancient place of pilgrimage, and especially of the restoration there of tongues that had been cut off, his truth-seeking heart was attracted towards that place. … When a watch of the night had passed, H.M., in order to give men a rest, alighted in the town of Desūha. … During that night a spiritual form—which had wondrous powers—appeared in the secret place of dreams. It recited the lofty rank of the world’s lord and restrains him from his intention. In the morning he mentioned the vision and returned.” ~ Akbar Nama III (p. 348)

- The story of Akbar having offered a chhatri at the Jwalamukhi temple is unverifiable as he appears to have never visited the place! Stories to that effect are local tradition without any historical records to corroborate them. However, Akbar Nama does mention that Akbar intended to visit the shrine and declares that difficulty in travelling prevented him from reaching the place. The prompting was clearly not hostile, and he may well have made a grant towards it even if he could not visit it because it fell within his domains.[5] It may be noted that Akbar had great reverence for the Sun and fire and he kept a perpetual sacred fire burning in his chamber the charge for which was given to Abu’l Fazl.[6] But the most important thing that this lore tells us is that Akbar did not have to ‘spread stories to show himself in a good light’. In his time, he was greatly glorified by Indians both menial and noble. The hatred against him was mainly borne by the Islamic orthodoxy.

- Jwalamukhi temple was never “taken” nor defiled, not even in the time of Firoz Shah Tughlaq, who is said to have spared it at the request of the Katoch king, as we are told by Firishta. (This is affirmed in the Tarikh-i-Firuzshahi of Shams-i Siraj ‘Afif, who however scoffs at the suggestion that the sultan held a chhatri over the idol there.[7])

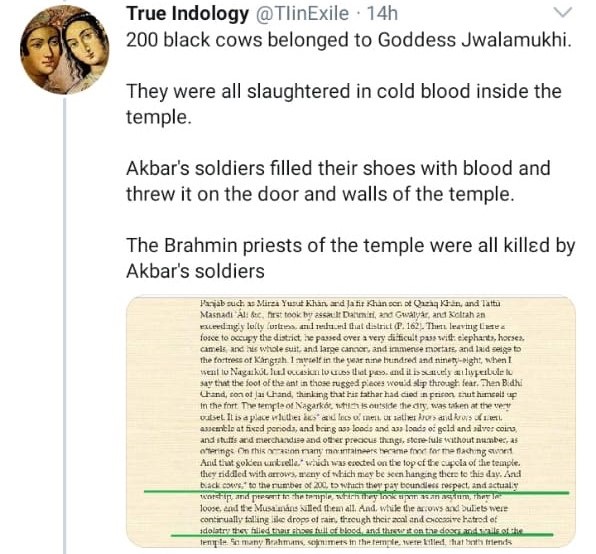

- The 1572 ‘siege of Kangra fort’ during which the Bajreshwari temple had been desecrated had been unsuccessful. This is attested by multiple sources:

“For ages none of the rulers of Hindustan who tried to take it had succeeded, not even Akbar. That sovereign sent against it Husain Quli Khan, Turkoman, entitled Khan Jahan, Governor of the Punjab. The fortress was invested for a long time, but the general had to retreat without effecting his purpose. The matter was left over for Jahangir to undertake.” ~ Padshahnama

“From the time when the sound of Islam reached the country of Hindustan up to this auspicious time when the throne of rule has been adorned by this suppliant at the throne of Allah, none of the rulers or kings has obtained possession of it. Once in the time of my revered father, the army of the Panjab was sent against this fort, and besieged it for a long time. At length they came to the conclusion that the fort was not to be taken, and the army was sent oft to some more necessary business.” (Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri)

“He [Akbar] granted the territory to Raja Birbar and detached a force under the command of Husain Quli Khan, Khan Jahan, Governor of the Panjab. While he was making the investment stricter and stricter the revolt of Ibrahim Husain Mirza took place. Forced by circumstances he [Khan Jahan] made friends with the Raja and started in pursuit [of the Mirzas].” (Ma’asir ul-Umara)

“In the beginning of Shawwal letters came from Lahore with the intelligence, that Ibrahim Husain Mirza had crossed the Satlada [Satluj], and was marching upon Dipalpur. Husain Quli Khan held a secret council with the Amirs about the course necessary to be pursued. The army was suffering great hardships, and the dogs in the fortress were anxious for peace, so Husain Quli Khan felt constrained to accede.” (Tabakat-i-Akbari)

Akbar Nama also provides a detailed account of the 3-month long siege of Kangra fort which had to be lifted owing to disturbances in Punjab.

- The Kangra fort (or Kot Kangra as it was also known) was successfully occupied, first since the long rule of the Katoch Rajputs from 1048 C.E., in Jahangir’s time in November 1620. Jahangir exulted at establishing Islam by slaughtering a cow/bullock there. This does not appear to have been carried out inside the temple since Jahangir mentions visiting the temple separately and later the Jwalamukhi temple[8] as well. But he obviously did not mind going against the general proscription on slaughter of bovines—which he himself upheld in spite of repeated pressure from the clergy—to symbolically mark this victory of Islam over kafirs. Jahangir was explicit in his contempt for the beliefs and common forms of worship and idolatry in Hinduism. (Instances of destruction of some temples beginning from Jahangir’s times on the emperor’s orders indicate that a move towards an Islamic state had begun right at the death of Akbar.)

The history of Islamic invasions in India is not just a story of an exclusive, violent ideology ravaging our land. It is also a mirror for us to see where Hindus failed as a nation, of our inadequacies and strengths, our doughty resistance against invading forces at times, at others defensive collaborations with them, of struggles and capitulations, principles and opportunism, pride and compromise, errors and foresight. Needless to say, this reviling of historic personalities from retrospective rancour contributes nothing to bringing this perspective. These are more in the nature of the coward’s resort that seeks his revenge in hatred.

More than anything, the Islamic invasions expose some fatal flaws of Indians: of lack of sustained scholarship in observing the invader and studying his mind, a lack of discernment in what exactly works(-ed) against us. And this will not change by spouting crude, historically inaccurate diatribes against invaders. It is only a continuation of this benighted attitude of Indians, not a sign of growing insight. Indians have become a whole lot more suspicious but still no wiser. We cannot see who our enemies and friends are, what serves our collective, what not.

Akbar was a ruthless foreign invader, especially in the initial stages of expanding and establishing his empire. The manner of reference to themselves in Mughal documentation also reveals that they saw themselves as outsiders, until at least the time of the fourth Indian Mughal Jahangir. The ‘Indianisation’ of the invading Islamic dynasties was a stratagem of Marxist writers to airbrush the exploitative nature of Islamic occupation. But it is also true that Akbar was a pioneer in criticism of Islam arising from among Muslims, the most powerful antagonist of Islam the like of which free India has not produced till date.[9] And even a supposed secular Constitution does not provide the safeguards and protections to non-Muslims from predatory Islam and the assurances of native rights that Hindus had in Akbar’s rule. Akbar strove to absorb from and integrate with the culture that he came to rule.[10] Akbar’s view of Islam in Bada’uni’s own words is described as follows:

“Every precept which was enjoined by the doctors of other religions he treated as manifest and decisive, in contradistinction to this Religion of ours [Islam], all the doctrines of which he set down to be senseless, and of modern origin, and the founders of it as nothing but poor Arabs, a set of scoundrels and highway robbers, and the people of Islam as accursed.” (‘Muntakhab-ut-Tawarikh’ Vol. 2, p. 262)[11]

By all means Akbar saw Islam for what it is, much clearer than any Hindu ruler ever has done in a thousand years, and purposefully tried to defang it. To not learn from this remarkable character will be a greater loss than having lost out in a military-political struggle in the past.

References:

1) ‘Tuzuk-i-Jahangīrī or Memoirs of Jahāngīr’ – Jahangir (Henry Beveridge tr.)

2) ‘The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India’ – Jahangir (Wheeler M. Thackston tr.)

3) Himachal Pradesh: A Survey of the History of the Land and its People – R. K. Kaushal

4) ‘History of the Panjab Hill States’ Vol. 1 – J. Hutchison and J. Ph. Vogel

5) ‘Ma’āthir ul-Umarā’ Vol. 1’ – Nawwāb Ṣamṣam-ud-Daula Shāh Nawāz Khān and Abdul Ḥayy (Henry Beveridge tr.)

6) ‘The Akbar Nama’ Vol. 3 – Abu-l-Faẓl (Henry Beveridge tr.)

7) ‘The Religious Policy of the Mughal Emperors’ – Sri Ram Sharma

8) ‘The Ṭabakāt-i-Akbari’ Vol. 2 – Khwājah Nizāmuddīn Aḥmad (B. De tr.)

9) ‘A History of India – Muntakhabu-t-Tawarikh’ Vols. 1 & 2 – Abdul-Qadir Ibn-i-Muluk Shah, Known As Al-Badaoni (George S. A. Ranking tr.)

10) ‘Theory and Practice of Muslim State in India’ – K. S. Lal

11) ‘The Ā-īn-I-Akbarī’ Vol. II, III – Abu’l-Fazl Allami (Col. H. S. Jarrett tr.)

Cover picture: Kangra Fort (Source: Wiki)

[1] Meant possibly Sirhind

[2] It may be noted that the Jwalamukhi temple in Kangra houses no idol. The deity, which is the Mother Goddess, is worshipped here in the form of a perennial flame that emanates naturally from an underground fissure in the rocks.

[3] On many occasions he acted against their excesses: “In the 12th year, when Akbar moved against Khán Zamán, H. Kh. was to take a command, but his contingent was not ready. In the 13th year his jágír was transferred from Lak’hnau, where he and Badáoní had been for about a year, to Kánt o Golah. His exacting behaviour towards Hindús and his religious expeditions against their temples annoyed Akbar very much.” (‘A’in i-Akbari’ Part-1 – Col. H. S. Jarrett, tr.)

[4] Bhavani’s temple below the Kangra fort which had been desecrated by the imperial soldiers in 1572-73 and the idol carried away was allowed to be repaired and the idol restored to its place of honour. It seems to have been given out that the Mughals had thrown the idol in the river nearby. A search for it was made in the river bed and the idol was ‘discovered’ and duly installed at the temple. Possibly a gold umbrella of the goddess was put up at that time. (Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri, p. 347 – S. R. Sharma) Alternatively, the legend could have arisen in this background.

[5] Akbar Nama III (p. 348) – Sri Ram Sharma (‘The religious Policy of the Mughal Emperors’)

[6] “From his earliest youth, in compliment to his wives, the daughters of the Rajas of Hind, Akbar had, within the female apartments, continued to burn the hom, which is a ceremony derived from fire-worship; but on the New Year festival of the twenty-fifth year after his accession (987 A.H., 1579 A.D.) he prostrated himself both before the sun and before the fire in public, and in the evening the whole court were required to rise up respectfully when the lamps and candles were lighted.” (‘Muntakhab ut-Tawarikh’ Vol. 2, p. 261)

[7] The idol refers to the one in the temple in Bhavan. Afif’s account is clearer and makes reference to both temples which were visited by the sultan.

[8] 1) “After finishing my tour of the fortress I went to see the Durga idol temple known as Bhawan, where an immense crowd of people wandering in the desert of error congregates. In addition to the miserable infidels who worship idols, hordes of Muslim folk traverse vast distances to offer vows and seek blessings by worshipping this black stone. Near the idol temple at the foot of a mountain is a sulphur pit so hot that tongues of flame continually leap out. They call it Jwala Mukhi and deceive the common people by attributing it to the idol’s miraculousness.” (Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri)

2) “Jahangir paid visit to Jawalamukhi in the neighbourhood. He was at first persuaded that the everburning flame in the temple was a trick of the priests. To confound them, he had a stream of water poured over the fire. This failed to extinguish the flame. He left the temple unharmed and gave order that the adjoining buildings be not only repaired but also added to.” (‘Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh’ 1695 C.E., Sujan Rai Bhandari)

[9] “Every doctrine and command of Islam as the Prophetship, the harmony of Islam with reason… the details of the day of resurrection and judgement, all were doubted and ridiculed [by people in the Emperor’s presence].” (Muntakhabu-t-Tawarikh’ Vol. 2, p. 307)

[10] “…one reason is most prominent—Akbar’s association with Hindu Scholars. His sympathetic and receptive mind willingly accepted the goodness that Hindus possessed and Hindu men of learning successfully conveyed to the King. Some earlier monarchs like Mohammad-bin-Tughlaq had also associated with Hindu saints and yogis but they had remained fundamentalists. It was Akbar’s genius that grasped the finer points of Hindu civilisation ‘skillfully represented’ by learned brahmins and he built up a political edifice on the oft-quoted principle of sulehkul, or peace with all.” ~ Kishori Saran Lal

[11] “And the story of the consummation of the Prophet’s marriage with Çadīqah* (God bless him and his family and give them peace!) he [Akbar] utterly abhorred. And all his other heretical attacks on orthodoxy who can speak of ! Would that my ears were filled with quicksilver, so that what things would they escape hearing! And the failings of all the prophets (God’s blessings, and His peace be on them all!) the Emperor cited as reasons for disbelieving…” (Muntakhabu-t-Tawarikh’ Vol. 2, p. 339)

*i.e. Aishah, who was only 9 years at the time.

Dear mrs Mukerji,

Thank you for providing this interesting insight into the relationship between Mughal emperor Akbar and his Hindu subjects.

This topic is often presented in two flawed ways, one by Marxist historians obviously trying to Indianise the invader and whitewash the atrocities of the Mughals; and on the other hand by right wing chauvinists who mostly cite from secondary sources which can be classified as atrocity literature at best.

Neither the downplaying of historical intolerance nor the exaggeration of it will provide India and Indians with the necessary insight to understand what lies at the core of the historical intolerance that it faced.

What I however do not seem to get from your analysis is the following: a clear cut explanation of Akbar’s policy towards his Hindu subjects. Your article seems to insinuate the fact that while he was an invader he was quite a tolerant one as compared to his successors and predecessors. You mentioned that most of the intolerance Hindus faced was by the hands of his individual soldiers that acted in violation of official state policy. In how far is this true since he is known to have imposed the discriminatory jizya tax on his Hindu subjects.

So what I would like to know is what the correct picture of Akbar is. Was he a tolerant and secular Muslim ruler full stop. Or was he a relatively secular and tolerant ruler compared to other Mughal rulers before and after him, but still intolerant towards non-Muslims in absolute terms?

Thanks for your comment!

This article was on a very specific topic. It was meant as a fact-based replication to one instance among the heaps of trash which is shared around in SM in the name of “history”. A detailed series on Akbar is one of the things we have in mind (because your question is important!), but at a later stage. It has been put off because we felt that it is more important to first bring out Hindu history, the story of our heroes (please see our series on Rana Pratap), rather than go on and on on foreign rulers about whom a lot has already been written.

History is a vast subject and there’s a lot of ground to cover. But unfortunately, it often gets hijacked to propagandist motives. Our view in contrast is: history should, nay… must be written exactly as it happened. Just as we analyse British personalities for their good and bad, why is it not possible to take a look at Mughals–at least the ones who were not outright Islamic bigots–in a similar dispassionate way? Blackening the enemy’s face doesn’t win us the civilisational battle! Hindus have to be honest in their assessment of the qualities of the invaders (why they won) and own failings (why we lost). Explaining the latter by proclaiming the other’s villainy is self-deceiving and defeats the very purpose of study of history.

Also, the concept of secularism as we know it did not exist in those times. Historical personalities have to be assessed in terms of the sensibilities of their age, in case of Akbar, against the index of religious tolerance in the 16th century Abrahamic world. Then one would have to concede that Akbar was pioneering! (Please also read the embedded link above to another article which should answer your question on imposition of Jizyah.)

Happy to have evoked your interest. Stay tuned!