By Col. C. M. Ramakrishnan (Retd.)

Swapnil Hasabnis (SH) caught up recently with Colonel C. M. Ramakrishnan, retd. (CMR) on chat to get his views on the recent India-China border crisis at Galwan valley, its background and likely fallouts. The article below contains his responses on the matter.

SH: Sir, to begin, can you give us an overview on the China problem?

CMR:

Disquiet in the northern borders

Pakistan has been in the act of violating our borders ever since the incursion of 1948. The Chinese too have regularly been sending in troops to violate Indian borders and occupy areas since at least 1956[1]. Vast tracts of Indian land have been occupied by these two neighbouring countries and have remained this way owing to a baffling Indian passivity and reluctance to recover them.

Viewing the actions of governments over decades, and judging by its results on ground, any Indian would be justified in the opinion that successive governments of India—irrespective which political party or combination of parties constituted the government: Indian Nation Congress, Janata Party, or Bharatiya Janata Party, with/-out their allies—have singularly failed to uphold the integrity of our borders and have endangered the security of the Indian nation.

The extent of irreparable damage that has been inflicted as a result of this to our country, due to wilful manipulation or plain stupidity and naïveté of successive political dispensations and bureaucrats over the decades, is getting harder to conceive for the sheer magnitude of it.

Seventy years have passed since Indian independence, and it is shameful that we still do not have a semblance of a coherent national security policy. The unassailability of our borders and the security of the Indian state is the foundation of our existence and continued survival as a nation. Political rhetoric apart, scant attention has been paid to what should be the primary task and core concern of any government, i.e. national security and territorial integrity.

The sidelining of this principle duty of a government over the decades has led us today to such a state that vast tracts of India have been snatched and lie under hostile occupation by India’s sworn adversaries, Pakistan and China. Not only has India been unable to regain the lost territories, it appears that if the Indian state continues in its listless way, we will end up losing much more in the future.

The Chinese incursion in Galwan valley, the martyrdom of twenty-two of our bravest men has led to great anger and outrage across the nation. There are demands for strident ‘action’, ‘throwing out the aggressors’, etc. At the governmental level there is a scurry for procurements of arms ammunition and special weapon systems in a kneejerk response. As the bodies of our brave martyrs are given final farewells with full military honours, and shortly a number of medals for bravery are also bound to be announced and their memories eulogised, it would be sobering to know that this tragedy and the accompanying spurt of emotion is just a replay.

The current tragic scenario is just a repeat of what has happened all along with each such invasion in the past. I do not even venture into the portion of history prior to 1947, when India gained independence from a foreign coloniser, but address only the unfortunate incidents thereafter. Such outbursts of popular sentiment and rage of Indians have been witnessed earlier as well, time and again. From the Indo-Pakistan War of 1948 in Kashmir, to 1965 in the Rann of Kutch and later in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), Punjab and Rajasthan, in the 1971 war as Bangladesh was created, and in 1999 in the Kargil War.

Seldom in these reactions has there been an element of thought on how is it going to be different this time? Or in the future?

There is a desperate need for Indians to learn from history, to first know history: each and every treaty concluded with countries, and military operations proposed and conducted. Unless deeper studies of the reasons for governmental actions are carried out and the pitfalls identified, India will never be able to learn from past actions and continue with the repetition of errors.

Systems and procedures followed by governments in the past only confirm the fact that the leaders, though representatives elected by the people, have almost never come out truthfully and in earnest on the real issues and problems facing the country. The executive machinery of the government, the bureaucrats are as unapproachable as they were in colonial times. Governments and Bureaucrats hiding behind the Official Secrets Act deny relevant and necessary information to the public. All possible methods from delays to obfuscation to non-appointment of RTI Commissioners are used to keep the public in dark on important facts and information that affect national security.

The recent information drought on the operations in Ladakh has only increased the apprehensions in the minds of ordinary citizens. The presence of media persons in the forward areas in Kargil operations kept the people informed of the real situation. This time around no media person has been allowed to move beyond Leh. Information that should come from governmental sources have to be gleaned from private persons, individuals with access to satellite photography in India and abroad.

Our present Prime Minister Narendra Modi, has the unique abundance of love, respect and admiration of the people of India, not seen since the days of Nehru or Indira Gandhi. But it is regrettable that PM Modi, who is so forthcoming on a hundred topics from Swachh Bharat Abhiyan to COVID protection, has not been upfront with our problems on border issues with China and Pakistan.

But then, are we aware that till date even the reasons for the disastrous setback, diplomatically and militarily, in the 1962 war, a tremendous loss of status in the international community, have not yet been fully analysed or examined? The only official enquiry that was conducted was a study by Lieutenant-General T. B. Henderson Brooks and Brigadier Premindra Singh Bhagat. This too was confined to military operational details. No study was conducted on the actions of Army Headquarters. Even this solitary report has not made it to public domain. The only version that is available is a supposed leaked account on internet by Australian author, Neville Maxwell, author of ‘India’s China War’[2]. But this is incomplete and unreliable.

No attempt has been made to study the reasons for omissions and commissions by the ministry of defence or the external affairs ministry. There is little doubt that the blunders committed by these two ministries have led to fiasco after fiasco in India’s security situation. Repeated capitulation of Indian interests on border issues and poor state of weaponry available to defence forces even seven decades after independence have never been examined, nor those responsible brought to book.

Jhappies, pappies, boat rides and bus rides cannot substitute for substantive economic and military power. Gimmickry never did and will not fetch Nobel peace prizes for our prime ministers. And even if they did, no individual fame of Indian politicians or the much-hyped ‘soft power’ will serve to secure India from hostile neighbours, as would a hard-headed, formally executed, consistently applied foreign policy, relentlessly and proactively focussed on maximising India’s clout and influence, letting not an inch to gratify any entity, not allowing any ideal of goodwill or addlebrained magnanimity cloud the vision that, not these, but sheer might, and aggressive, assertive bargaining at the diplomatic level will stand India in good stead.

India expects Prime Minister Narendra Modi not only to put national security as an utmost priority, but also institute systems to analyse records of decision making, identify lacunae, and formulate definite policy to ensure there are no repeat errors.

SH: Considering the differing versions from various quarters, and for a better understanding of every Indian, could you relate the historical background of this conflict?

CMR: First of all, it is necessary to understand that the incident of June 15, 2020, at Galwan valley, where the Chinese army brutally attacked and killed 22 Indian Army personnel, who were constrained on account of orders to not use arms even when attacked, is not a one-off incident. Several such incidents have happened in the past. It is only that Indian public was either not aware of their seriousness or has entirely forgotten these incidents. The foreign ministry and ministry of defence have managed to keep such incidents under wraps and/or shove them under the carpet.

Two such older incidents I would like to mention here, when India’s strong response in 1967, under Indira Gandhi as PM, had compelled China to tone down violence against Indian army personnel, and that set a status quo which continued until recently.

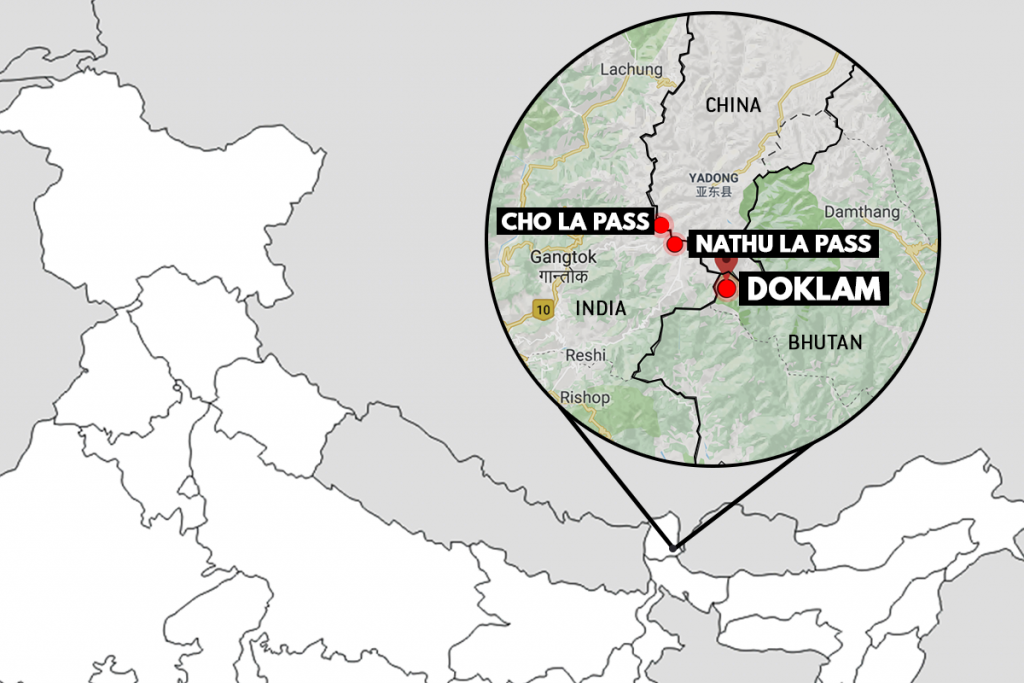

Nathu La and Cho La Clashes, 1967

In 1964, the Chinese had started moving troops to the Sikkim border leading to tension on that front.

In December 1965, a patrol of Assam Rifles was attacked by Chinese troops at around 18,000 feet in the Giagong Plateau in North Sikkim and the patrolling Indian soldiers were killed. Chinese troops had installed loudspeakers and played incessantly propaganda songs and news that reminded Indian soldiers dug in their trenches of the debacles of the 1962 war. Consequently, XXXIII Corps under General G. G. Bewoor had decided to vacate the Jalap La and Nathu la passes. However, General Officer Commanding (GOC) 17 Mountain Division, Major General Sagat Singh, refused to vacate the Nathu la Pass.

On Aug 20, 1967, Indian troops, approx. 120 in number, commenced laying barbed wire fence on the border to prevent further incursions by the Chinese. Suddenly, over seventy Chinese under a party Commissar advanced with their weapons in battle ready position. Indian troops under Major Bishen Singh did not budge. The Chinese returned to their bunkers. There was relief that things did not come to a head.

The next morning an Indian patrol was jostled and pushed by the Chinese. No weapon firing took place. On September 11, around 7 AM, when the wire laying was in progress, about 150 Chinese soldiers turned up, and again there was pushing and shoving, but no weapons fired. The Chinese then stopped and went back to their bunkers, another time people breathed easy as it did not get worse.

Suddenly around 7:45 AM there was a whistle from the Chinese side and all hell broke loose. The Chinese started incessant firing from within their bunkers at the Indian soldiers out in the open. In the initial barrage itself more than one hundred Indian soldiers including their Colonel Rai Singh, Commanding officer 2nd Grenadiers, were killed or injured. The firing went on relentlessly for nearly 30 minutes. Colonel Singh was killed with a bullet through his chest.

Major Harbhajan of 18 Rajput Regiment led a counterattack but could not reach the Chinese bunkers which were situated at a much higher height, and this led to many more Indian lives lost in the counterattack.

It was a deliberate move by deceptive and cowardly Chinese troops hiding in their bunkers to open fire and kill Indian soldiers out in the open. The understanding of not using weapons was trashed by the Chinese, to the detriment of rule-abiding Indian troops.

A clash on almost similar pattern took place a few kilometres north of this location in another pass at the Sikkim-Tibet border, in Cho La, shortly after on October 1.

Indira Gandhi took the matter seriously and gave the army a free hand with minimal restrictions to deal with the Chinese. This enabled the Indian Army to initiate necessary action that proved to be an inflection point. More than 340 Chinese were killed in Nathu la Pass and 35 more in Cho La. Chinese bunkers and bases far behind the front line were destroyed by Indian artillery fire. The forceful counter attacks by the Indian Army sent shockwaves through the PLA. Their front lines were withdrawn by more than 3.5 kilometers and the Chinese came forward with a changed mindset in the subsequent meetings for a stand down.

There was no gain of territory, but the ghosts of 1962 were exorcised.[3]

SH: Talking of PM Indira Gandhi’s time, what was ‘Operation Falcon’? What was it meant to achieve? What ultimately was the result?

CMR: The experience of 1962 had the Indian army commanders, starting with General Manekshaw, who had taken over as General Officer Commanding IV Corps, impress on the government the need for improving infrastructure on the borders. But regrettably, the bureaucratic and political mood was that of pursuing woolly-headed conciliation than practical war-preparedness: “Each time, Indian Intelligence agencies thwarted their attempts saying that it would be seen as a provocation by china and lead to war.”[4]

One Step Forward

An expert committee report (1975) on restructuring of the army, set up by Chief of the Army Staff (COAS) T. N. General Raina, consisting of Lieutenant General K. V. Krishna Rao,[5] and Major Generals K. Sundarji and M. L. Chibber (both went on to become COAS) was made to gather dust. Luckily, Gen. Krishna Rao had an opportunity to present it to Indira Gandhi in June 1981.

Krishna Rao expressed the opinion: “I must say that Prime Minister Gandhi had an excellent understanding of defence matters.”[6] The meeting is described by him as follows:

She immediately agreed and asked how much time will be needed to complete the project and of any implication… Gen. Krishna Rao replied that it could take up to ten years and added “this could lead to war.”

“So what”, asked Indira Gandhi. Gen. Krishna Rao replied that the Indian army will fight it out and will not stop even if the Chinese objected. Gen. Rao also mentioned that China is not likely to use nuclear weapons. The dynamic lady immediately gave assent but told the army chief that in the event of a war with China, Tawang and Arunachal Pradesh should not fall into enemy hands again.

It was a great day! Operation Falcon was launched in 1981 which gave a shot in the arm to the defence forces to effectively neutralise Chinese ingressions. Disguised as routine exercise in forward areas it was designed to secure the forward defences in Ladhak, Central Sector, Sikkim and North East by enabling the defence forces to upgrade the sporadic deployment along LAC with China. It was left to Gen. Krishnaswamy Sundarji, when he took over as COAS in February 1986, to execute the plan and see it to fruition. After successful operations in the Tawang sector carried out in the 1987 Sino-Indian skirmish, it was suspended mid-way just when India looked finally on her way to assert her valid territorial claims.

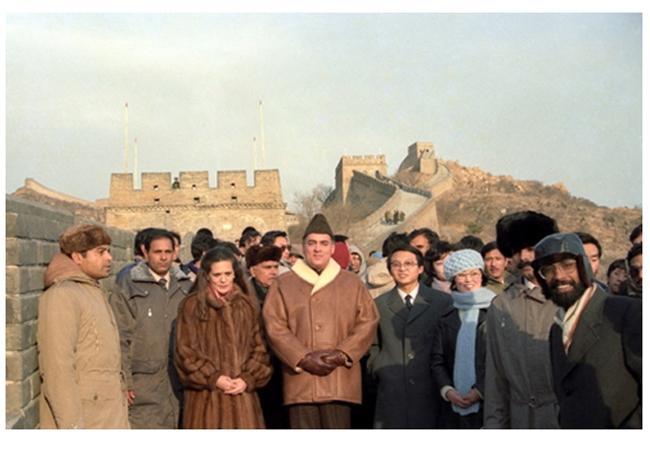

Two steps back

In December 1988, Rajiv Gandhi as the Prime Minister visited China. Probably basking in the adulation he got in China and India, “as a goodwill measure” Rajiv Gandhi unilaterally ordered a cessation of Operation Falcon which was meant to improve Indian defences. Disconcerted Indian military commanders protested to the defence minister K. C. Pant, but it was to no avail. The much-needed progress on infrastructure projects to connect forward posts was stalled.

“…unfortunately, Indian prime ministers since Rajiv Gandhi have neither assessed the disputed border as India’s core concern… … …nor understood the effect of border dispute has had on India’s rising stature. There has instead been pressure within the establishment to make prime minsters’ visits to China appear a grand success. Consequently, appeasement policy followed by India has worked to China’s advantage. The Chinese detest appeasement, which they view as a sign of weakness and exploit.”[7]

Question is, who had advised the Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi to take this retrograde step? The Chinese, of course, not being short-sighted or naive, continued building up over the decades all along the border. And for that colossal foolishness of the Indian PM the Indian troops are paying till this day in 2020 to China’s advantage.

SH: Prime Minister Narendra Modi went personally to Leh earlier this month and warned that expansionism will not be tolerated. India will not give up an inch of its territory. Indian Army, paramilitary forces backed by IAF are also deployed on the border in heavy numbers. Will China take heed of the Prime Minister’s warning and to suspend its aggression and fall back to its old positions?

CMR: No. It is pure naiveté to believe that China, which considers itself to be much more powerful than India, will cease its aggression just with a warning from an Indian Prime minister. It needs much more determined handling and consistent show of strength and controlled aggression. Whether the Indian state apparatus develops the resolute application required for this, remains to be seen. But from its past showings it does appear as being too hopeful.

SH: Then what was the purpose of such a visit and address by PM Modi?

CMR: PM Modi’s visit to meet the troops on Ladakh and addressing them and the nation was a message to China and the world that India is determined to face any aggressor. What is important is, how India follows up on this. It was simply meant to improve the morale of the Indian fighting forces at the border, which does have a bearing on the spirit of our men. But it needs stout backing with a sound foreign policy and an unimpaired vision of the leader.

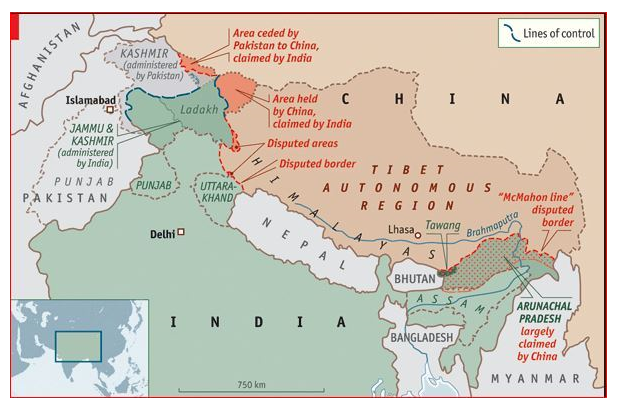

SH: Is any portion of Indian territory under Chinese occupation as of today in July 2020?

CMR: This will come as most unpalatable, but the truth is, yes. Nearly 50,000 sq. kms of Indian territory is under illegal occupation by China. The largest area of land under Chinese force occupation is in Aksai Chin in Ladakh, occupied in 1956. They are also in possession of Saksham valley in Kashmir. Pakistan handed over this portion of Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) i.e. to China on March 2, 1963. Feeble protests by India brought placatory remarks by the Chinese, but without any show of will on the India side to pursue the matter. And thereafter the Indian ministry of foreign affairs drifted into hibernation.

An additional 640 sq. kms was occupied in Ladakh by China in 2013. In 2013, former Foreign Secretary, Shyam Saran, who was at that time Chairman of the National Security Advisory Board (NASB) under the National Security Council (NSC) of the Manmohan Singh government, after his visit to the region had informed the government that the PLA patrol had set a new Line of Actual Control (LAC), thus occupying 640 sq. km of Indian territory in Eastern Ladakh.

SH: Is it true that China is claiming even more territory from India?

CMR: The answer to that too is an unpleasant, yes. China is claiming even larger parts of India. China has been claiming large parts of India, more than 130,000 sq km in Kashmir, and North East in Arunachal Pradesh.

As per the latest report of July 6, China is claiming parts of Bhutan as well.

SH: How can China just claim territory that belongs to India?

CMR: The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has perfected the methods and nefarious practices adopted by the early Chinese empires and governments. Even a cursory glance at the maps of Chinese empires will clearly indicate that the Chinese always had this propensity and greed to expand its territory at the expense of its neighbours.

Chinese expansionist designs are promoted by the fact that India and China have a frontier, rather than a clearly demarcated border. After Indira Gandhi, successive Indian prime ministers have not dealt with the border issue seriously. This is an appalling lack of vision! Indian foreign policy has been defined by appeasement of the China. This has encouraged China to make untenable claims on Indian territory.

SH: But how can this be? Are our borders not clearly indicated on the map?

CMR: Insofar as India is concerned, it has been basing its territorial limits on maps as applicable in 1947. It is the Chinese who have been changing their stand on territorial claims and have never agreed or given approval to any map so far.

McMahon Line

British India had convened a conference in 1914 in Simla, attended by representatives of China and Tibet, to draw up a line separating British India and Tibet. It was hosted by Sir Henry McMahon, the then foreign secretary. In the conference, lines were drawn up (McMahon line) on maps indicating the border between British India and Tibet, Tibet and Bhutan, a boundary between inner regions of Tibet and its outer regions. China did not accept and ratify the treaty as it claimed that its representatives had initialled it under duress.

Initially China had objections to the inner and outer lines of Tibet. In 1936, a Chinese atlas claimed territory south of McMahon line. The first claim to Indian territory, south of McMahon Line by Chinese Communist Party government was made in 1959.

Western sector

There has been a great deal of correspondence between India and China since the time of Nehru and Chou En-Lai. The Treaty of Chushul was signed between Maharajah Gulab Singh of Kashmir, the Chinese Qing Emperor Guangxu and Lama Guru of Lhasa (Dalai Lama) in 1842. The above boundary was accepted by China in 1847. However, the Chinese base their territorial claims on another earlier agreement, the Treaty of Tinmosgang, between Ladakh and Tibet in 1684, that ended the 1679-84 Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War.

SH: When did the problems of Chinese incursions begin and what did the Govt of India do about them?

CMR: Post 1947, the new Indian government took as its boundaries those areas claimed by Britain for decades. Thus, India considered Aksai Chin as part of the state of Kashmir. But the rulers in Peking had other ideas about this.

Aksai Chin

In March 1956, PLA began construction of a military highway between western Xinjiang and western Tibet, directly across the Aksai Chin plateau, an area which the Indians clearly believed to be Indian (south of the Johnson-Ardagh line). This road (1200 kms) was completed in October 1957.

It is a telling story on Indian ineptitude that the government was completely unaware of this massive encroachment by Chinese forces and road project until September 1957! It was only in July 1958 when Chinese published maps of the road which showed Aksai Chin as Chinese territory that the Government of India (GoI) woke up and made a protest to China. It then sent two patrols to recce the road and bring back information. The Chinese held them in detention for nearly a month.

Galwan and Chip Chap Valley

In July 1962 a platoon of Gurkhas (30 soldiers) was dispatched to cut off Chinese outposts in Galwan Valley in Aksai Chin. On July 10, a Chinese battalion of over 600 men surrounded the Indian post and cut off its supplies. Indian reinforcements were blocked and no supplies were allowed to go through. Air dropping had to be resorted to in order to ensure minimum supplies. India was unable to dislodge the Chinese from Aksai Chin in 1957 and the occupation continues even today.

On July 21, there was a skirmish in the Chip Chap Valley. Two Indian soldiers were wounded, the first since Konga Pass skirmish in 1959[8]. The Chinese protested, and also accused India of violating the McMahon Line in NEFA.

SH: What is LAC with regard to China? How does it effect Indian territorial integrity?

CMR: LAC stands for ‘Line of Actual Control’ which is different from a frontier, a border, boundary or a line on a map demarcating any of the above. LAC demarcates the exact line on the ground up to which a body of soldiers can actually control by physical occupation, intense patrolling, or fire. Crossing the LAC will be taken as a transgression and can lead to serious consequences. It needs to be understood that LAC can move forwards or backwards from a border. For best effects it should be clearly demarcated on the ground. It can be in the form of pillars, or even fencing.

After the war in 1962, Chinese army voluntarily withdrew from the Eastern Sector in NEFA completely, moving north to about 1.20 km of their 1959 claim. This strip of ground became a de-militarised zone of sorts, but with both sides sending out their patrols.

However, in Ladakh, the Chinese continued to occupy area in Aksai Chin, though behind their claim lines of 1959. Aksai Chin lies between the Kun Lun Mountains and the Karakoram range. India claims Aksai Chin as a part of Ladakh as Indian territory. However the actual control of a large tract of land was and is with the Chinese. Thus the limiting line of Chinese claims, a 320 km line, became the LAC, post 1962.

SH: But now we talk of LAC running to over 2000 kms? Is this correct? How did this happen and when?

CMR: Yes. As already said, initially just after 1962 LAC was limited to the area occupied by the Chinese in Ladakh, Aksai Chin. Even though China refused to accept McMahon line in toto, McMahon line was the designated border for the Central and Eastern borders.

Today in 2020 the LAC extends all along the Indo-Chinese border. The Chinese have made full use of the Indian naiveté, incompetence and ignorance of the diplomats and politicians engaged in border negotiations. Indian diplomats engaged in discussions with the Chinese over the last six decades have repeatedly failed to understand how the basic effects and implications of treaties and ‘understandings’ will actually be implemented on ground.

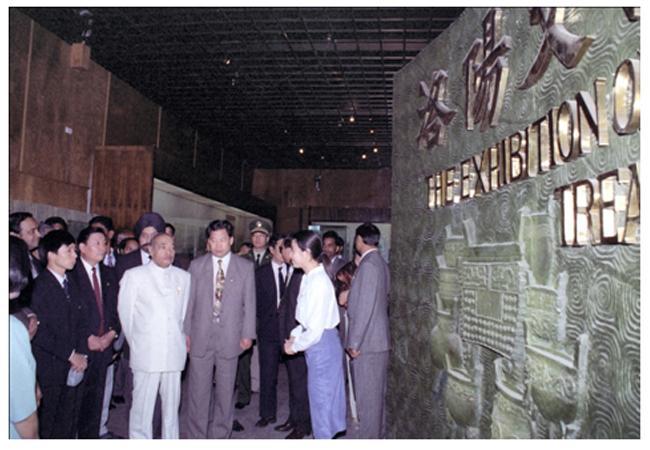

PV Narasimha Rao

Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao visited China in 1993.

Rajiv Gandhi had already by then sidelined and diluted the border issues which were of utmost importance to Indira Gandhi and replaced them with ‘overall relationships’. Three working groups were formed following this to deal with economic relations, trade, science, technology and also border issues.

PM Rao compounded the matter when he reverted to the approach adopted by Nehru that minor adjustments could be made, but not any major deviation. (Here it will do well to remember that Nehru had already summarily rejected a possible resolution of the border issues with China: exchange of the Chinese occupied territory in Leh, to their dropping claims in NEFA and acceptance of McMahon line in the east.)

Chinese were of course very happy with the revised Indian approach.

“China responded by saying that the entire border should be called the LAC, without prejudice to the border position of the two sides. China told India that with the LAC in place, troops could be withdrawn sector-wise instead of waiting for lac and border agreements. The agreed sectors could then have ‘mutual and equal security’ as agreed by the two sides.

The hand of the PLA was evident in the Chinese offer, while India—much like during the Nehru years—did not consult its army while making its border decisions.

Rao and his civil advisors failed to understand that LAC by definition would be easier to alter than a disputed border even it was not agreed on maps or the ground. Being a military held line, it can be changed by force.

Rao government fell for the ploy and the two sides signed the Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement during Rao’s China visit in Sept 1993.

With the stroke of a pen, the entire disputed border was renamed the Line of Actual Control.”[9]

LAC and areas of Concern

The Border Peace and Tranquillity Agreement (1993) added immensely to the problems of the Indian army in all operational and administrative matters. The number of border skirmishes has increased by leaps and bounds since then.

The Chinese have been asserting their claims by pushing patrols into what they claim to be their areas, testing for weakness, probing continuously to spot areas that they can occupy.

India has been fooled into accepting the sector by sector approach. Today the military commanders do no not know what the area is that they have to defend. Is it the McMahon line with watersheds as border, or areas occupied by China giving with LAC becoming a new border? With advancing claims by China every now and then, what is he supposed to defend?

Bureaucrats in the foreign office have been weakening the Indian position on border issues repeatedly, through ignorance of realities on the ground. “The approach adopted by mandarins in the foreign office make little military sense.”[10]

The question that arises naturally is was PM Narasimha Rao was not briefed by foreign office on Nehru’s and Indira’s views on LAC? Why was the army which had the responsibility to defend the border not consulted?

India rejected the concept of LAC in both 1959 and 1962.[11] Even during the war, Nehru was unequivocal: “There is no sense or meaning in the Chinese offer to withdraw twenty kilometres from what they call ‘line of actual control’. What is this ‘line of control’? Is this the line they have created by aggression since the beginning of September?”

The recent incursions in Galwan Valley, Fingers, etc. are just a repetition of earlier actions by the Chinese. PLA has in place a very workable ‘Forward Policy’ of its own.

Joint working groups have been meeting to identify pockets of dispute. In every meeting Chinese add additional areas. In 1995 there were 8 pockets of dispute. In 2015 there were 12. The Pangong Lake area was not a disputed area in 1995. But since 1998, Chinese have been patrolling in powerful boats, ramming, and capsizing smaller Indian boats with impunity.

Today the LAC covers the entire border in Kashmir to Mizoram. It is claimed to be 3422 km, some calculate it to be 4023 km. Nobody knows for sure. No one has actually walked down the line to measure it.

Another major area of concern is that China which initially stipulated around 3488 km of LAC has changed its tune. In December 2010, China unilaterally declared that it shares only a border of 2200 km with India. Middle sector 554 km, Sikkim. 198 km and Eastern sector 1226 km. In other words, it has implied that POK is a part of Pakistan and so is Kashmir. It also claims that it has no border disputes with Pakistan.

Blunders one after the other by Prime Ministers Atal Bihari Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh are shameful reminders of how Indian positions on the security of its borders have been diluted time and again. Immature actions by past Prime Ministers Satish Gujral and Morarji Desai have dealt serious blows to Indian security interests. In the absence of any serious examination of actions and motives many more individuals behind the outrageously imbecilic decision-making have never been identified or taken to task.

SH: So how did it all start in 1962?

CMR:

A Brief on Prelude to 1962

Problems due to border issues commenced soon after independence. Pakistani invasion of Kashmir in 1948, along with internal issues of dealing with resettlement of refugees, bifurcation of states and a host of others were enough distractions. Pakistan aligned with USA, received large quantities of arms and equipment, and additionally support in all international forums. Border issues with Pakistan took the major share of attention all around. Added to this was the illusion of ‘Hindi Chini bhai bhai’ bonhomie created by PM Nehru and his close confidante and Defence Minister Krishna Menon. They did not expect, notwithstanding the major differences on border issues with China, that it would brazenly send its troops across the border. But that was what China did in October 1962, and inflicted heavy casualties on the Indian army in the North East, overran Indian posts and nearly descended to the plains.

In hindsight, for all that followed, arrogance, foolishness, lack of understanding of realpolitik, misreading Chinese minds, or simply bad assessment, incorrect judgement… there are many descriptions one may pick from. But it remains a testimony to all that is wrong with Indian state policy and leadership, a stark lesson disregarded for long, but hopefully not for ever.

As I said earlier, in 1956, China entered Ladakh and started to lay the road in Aksai Chin, India was unaware of the same till the matter became public in 1957-58, which was due to new maps released by the Chinese incorporating Aksai Chin in to their territory. It resulted in a great deal of agitation in the country. Nehru, whose wisdom had been unquestioned till then, was hauled up in the parliament and in public by the opposition.

In October 1959, Indo-Tibet border became the responsibility of the Indian army. It was ordered to patrol border areas that had not been demarcated and to set up posts in the inhospitable terrain of Ladakh. During the period 1959-61 Chinese were building up their strength and improving their communications, and as such were not expected to launch a major offensive in 59-60. But they had by then inducted a regiment and could bring forward some tanks. Initially, Indian Army had after an appraisal planned for a Brigade and two battalions of J&K militia to be sufficient to cater to thwarting Chinese moves.

The Chinese however continued to build up and consequently a reappraisal was made through a simulated war in Western Command in October 1960. The outcome of the gaming exercise was that they thought it prudent now to place a minimum of one division with a complement of tanks and support services in Ladakh to meet and eventual enhanced Chinese threat.

There was already a major problem with logistical support for Indian army posts set up Ladakh. While the road up to Leh had been completed by 1961, in the absence of any ground connectivity, all other 24 posts had to be supplied by air drops. Bases in and around airfields like Chusul were comparatively easier to maintain.

SH: You mentioned a term ‘Forward Policy’ earlier. What was this?

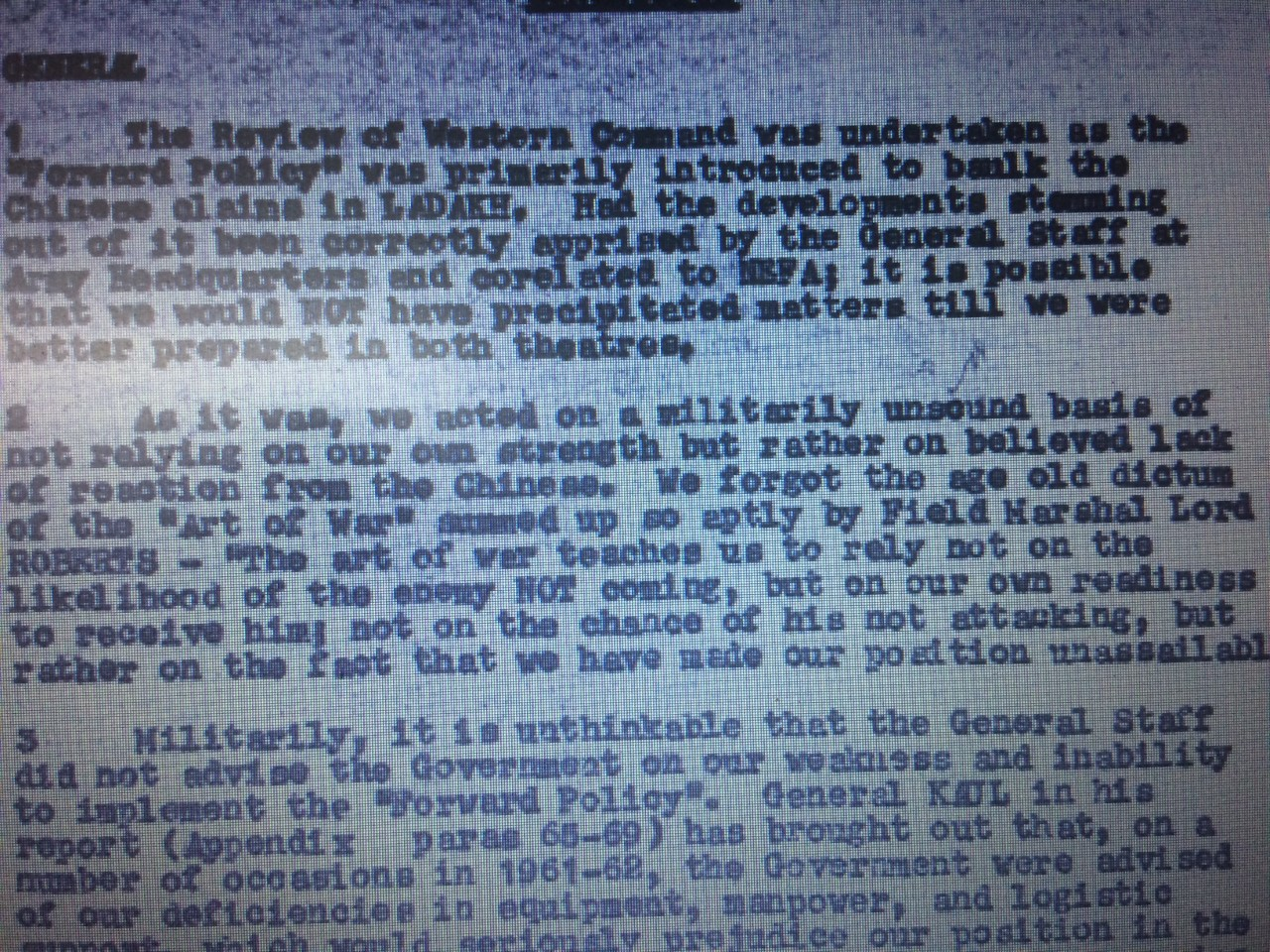

CMR: The infamous ‘Forward Policy’ was introduced in November/December 1961.

There was a major shift in the way the government of the day viewed border issues with China once the opposition and public criticism started in 1959. Realisation, albeit slowly, was dawning on the Nehru government that ‘Hindi Cheeni Bhai Bhai’ hokum was egregiously misplaced and not reciprocated in the smallest measure by China, especially on border issues. The government was on the back foot and had to demonstrate its ability to face up to the Chinese challenge. Although Nehru still turned down enhancing military spending[12] or looking towards improving war preparedness, GoI decided on implementing what came to be termed as the ‘Forward Policy’.

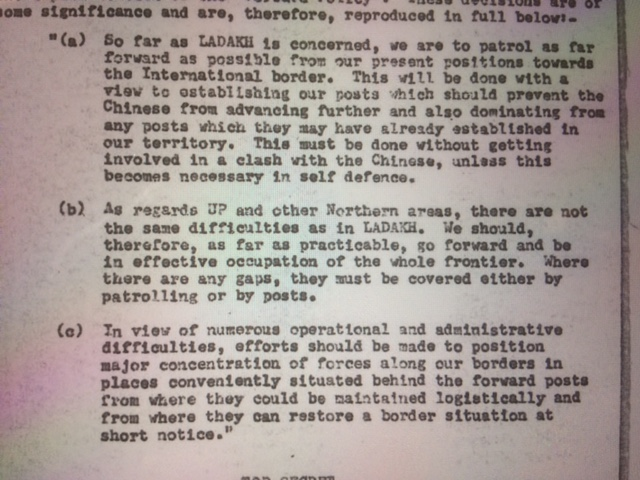

The Forward Policy virtually meant the establishment of posts to dominate Chinese positions in Ladakh and NEFA. It involved placing Indian outposts behind the Chinese lines so as to cut off their supplies and forcing them back to China. Obviously, this was bound to increase friction and possibly violent reactions by Chinese troops.

The Forward Policy virtually meant the establishment of posts to dominate Chinese positions in Ladakh and NEFA. It involved placing Indian outposts behind the Chinese lines so as to cut off their supplies and forcing them back to China. Obviously, this was bound to increase friction and possibly violent reactions by Chinese troops.

Reason for Indian government’s Forward Policy is not known. A meeting was held in the office of Prime minister on November 2, 1961. It was attended, among others, by the Defence Minister, Foreign Secretary, COAS, and Director Intelligence Bureau (IB).

Director IB opined that the “Chinese would not react to our establishing new posts—and that they were not likely to use force against any of our posts even if they were in a position to do so.”[13] This was contrary to the Military intelligence appreciation annual review of 1959-60, that clearly indicated that Chinese would resist by force any attempt to take back territory held by them.

So the ‘Forward Policy’ was to be implemented. It was but without adequate infrastructure or resources. Penny pockets of posts were created all along the border from Kashmir to North East, with no access roads and limited administrative support. Troops took 5 to 6 days to reach their posts from their base camps. Maintenance of forward posts turned into nightmare.

When the Brigade Commanders and Division Commanders raised issues of infrastructure, communication and maintenance, Army Headquarters was silent.

Chinese did not accept the additional posts and patrols lightly. The two sides were within striking distances and a number of firing incidents took place.

A reappraisal was done by Western Command in August 1962. It clearly reflected facts on ground. Chinese had a full division with supporting arms in Ladakh. Indian army was thinly spread out and had no supporting arms. Infrastructure and communication problems continued to persist. The reappraisal went on to stress the gravity of the situation.

It clearly said:

“In view of the foregoing , it is imperative that political direction is based on military means. If the two are not correlated, there is a danger of creating a situation where we may lose both in material and moral sense much more than we already have. Thus there is no short cut to military preparedness to enable us to pursue effectively our present policy aimed at refuting the illegal Chinese claim over our territory”.

Unfortunately, the Western Command was not provided with additional troops nor was any action taken politically or diplomatically to diffuse tension.

NEFA

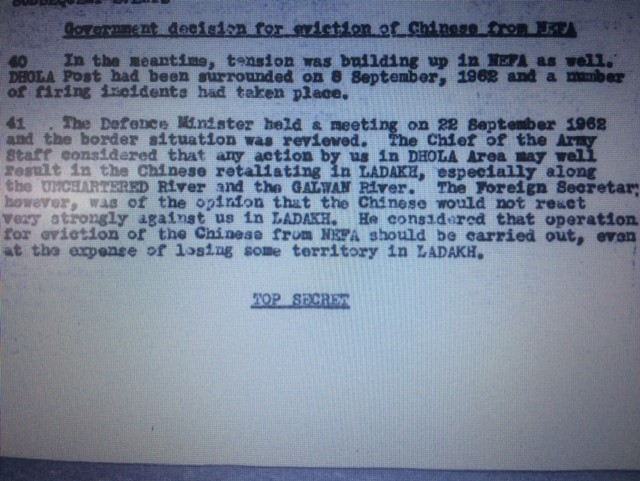

Meantime tension was building up in NEFA too. Dhola post had been surrounded on September 8, and the then Defence Minister Krishna Menon held a meeting on Sept 22 1962 to review the border situation. What transpired in the meeting was an uncritical acceptance of the statement that China will not retaliate to any forward movement by IA.

As stated earlier, assessments by the army of Chinese build up and possibility of retaliation were not taken into account. On what information did IB and the foreign ministry base its assumption that the Chinese would not retaliate is a question that has never been asked seriously nor answered.

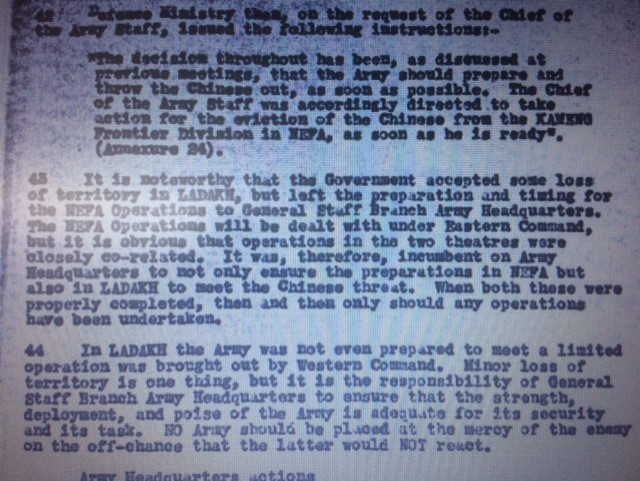

Indian army was asked to ‘throw out’ the Chinese from Indian territory. No cognisance was taken of the fact that Indian army at the time was simply not strong enough or equipped for the task.

To write about what followed would be painful to recount but is summarised in the following excerpts:

“In summary, the Indian army was in a poor state, especially in their readiness for alpine warfare. Their fire power, supply system, training, and readiness for mountain operations were all quite lacking. They had significant personnel shortages, and would often be outnumbered by the Chinese by 5:1.2 To pit troops in such circumstances against an enemy superior in every detail of military strength would be absurd; to leave them in an early winter of heavy snow and freezing temperatures would be to condemn them to steady and severe attrition from exposure and illness and, before long, starvation. But this is what India did.”

“At one point, Nehru had announced that 6,277 Indian soldiers were captured or missing. India’s casualties for the Border War were finally reported as follows:

Killed

1,383 Captured

3,968 Missing

1,696 “China released no casualty figures.”India released no figures for wounded, but casualties were high.”

“The significance of studying the China-India Border War lies in two areas: the military lessons to be learned, and the impact of the Border War on subsequent world history. The swift defeat of the Indian forces by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army emphasizes the following lessons: beware of assumptions; good intelligence is important to success; logistic/supply readiness is vital; one must be prepared for special (e.g. alpine) warfare; politicians can’t ignore the advice of senior officers regarding military readiness; and, generalship and command is important.”[14]

To be continued…

Cover Picture: Manorama

Featured Image: Indian Express

[1] Incursions at the Shipki La pass

[2] An account that whitewashed the Chinese aggression and put the blame for the 1962 war at India’s door, and towards this end quotes the Brooks-Bhagat report in a fragmentary manner.

[3] Account from ‘Water shed1967, India’s Forgotten Victory over China’, Probal Dasgupta

[4] ‘Chinese Threat’ (DOD), p. 39

[5] In August 1974, as Lieutenant General took over command of the largest corps (XVI Corps) in the Jammu Region, and 1975-76, was appointed Chairman of the Expert Committee constituted by the Government on Re-organisation and Modernisation for future defence of the country.

[6] ‘Chinese Threat’ (DOD), p. 39

[7] ‘Dragon on our Doorstep’, Pravin Sawhney & Gazala Wahab (p. 34)

[8] In October1959, while attempting to establish posts at Tsogstsalu, Indian troops crossed the Kongka Pass Hot Springs, and Shamal Lungpa. (China considers the Kongka Pass as its boundary with India, whereas India regards Lanak Pass further east as the boundary. The LAC arising from the 1962 war puts Tsogstsalu and Hot Springs on the Indian side and Shamal Lungpa on the Chinese side.)

On October 20, an initial Indian reconnaissance team was captured by the Chinese forces. A larger search party sent to look for them on October 21, encountered Chinese at a hill near Kongka Pass, which led to a firefight. Being in a more favourable position the Chinese managed to inflict 10 losses out of a total of 70 Indians, and 10 further (including the 3 captured earlier) were taken prisoner. One Chinese soldier was killed. The incident contributed to the heightened tensions that led to the 1962 Sino-Indian War.

[9] ‘The Chinese threat: Dragon on our Doorstep’, Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab, p. 44

[10] ‘Seal of Trouble—The 1993 agreement adds to woes of the Indian Army’, Pravin Sawhney and Ghazala Wahab

[11] ‘Line of Actual Control: Where it is located, and where India and China differ’

[12] ‘Henderson Brooks Report: An Introduction’, Neville Maxwell (the report was only–partially reproduced–by the author)

[13] §2, p. 8 (Maxwell in ‘Henderson Brooks Report: An Introduction’)

[14] ‘The China-India Border War’, James Barnard Calvin

Read the next installment of the talk with Col. C. M. Ramakrishnan here.