K. V. K. Murthy

There is nothing like a military situation to signify individual character: two diametrically opposite responses by two officers of the same rank, to a common order from a superior are as good as indelible brands on their persons. And it is usually the contrarian one—the one who chooses to disobey judiciously, no matter the personal cost—whose judgment is eventually vindicated, who emerges the hero, and goes on to higher things.

In September 1965, in the slipstream of India’s brief war with Pakistan, China decided to help along her new-found ally by creating diversionary trouble for India on the Sikkim-Tibet border. Against a backdrop of increasingly strident diplomatic exchanges following a ludicrous allegation of sheep and cattle theft, the Chinese decided to mass troops behind two passes held by the Indians, Jelep La and Nathu La, in a bullying maneuver. The responsibility for these passes lay with two divisions, viz. 27 Division and 17 Division, commanded by Major General Harcharan Singh and Major General Sagat Singh, respectively. Both divisions were part of the formation called 33 Corps, headquartered in Siliguri under the command of Lieutenant General G. G. Bewoor.

The situation at the two passes was tense, with Indians holding their ground against unrestrained Chinese provocation; there was no use of firearms yet, but Indian troops laying a border fence were frequently bullied and interfered with. The Corps Commander (Bewoor)—possibly as a measure of de-escalation, and perhaps with vaguely tactical intentions—ordered his two Divisional Commanders to withdraw their men some eight or nine miles inland from Jelep La and Nathu La.

Harcharan Singh of 27 Division complied with alacrity. The Chinese promptly occupied Jelep La—for the historically-minded, the same pass through which Younghusband and his mission made their way to Lhasa in 1903-04—and the pass was lost to India for good.

But Sagat Singh of 17 Division refused to obey Corps’ orders. He decided his men wouldn’t budge an inch from Nathu La, come what may; and what’s more, set about methodically strengthening its defences. He knew he was risking his superior’s displeasure, possibly his career; but he also knew withdrawal would spell disaster, for it would lay the fragile Siliguri Corridor open to the Chinese now that Jelep La was gone.

Two years later, in September 1967 his 17 Division would give the Chinese a memorably bloody nose at Nathu La—quite literally too, since an infuriated Jat managed to knock down a pompous political commissar, breaking both his nose and his glasses (strangely reminiscent of the recent broken nose episode in Galwan). The battles of Nathu La, and Cho La (a slightly lower pass to the east of Nathu La) were savage, vicious and expensive, with some splendid heroics—the Gorkha Debi Prasad Limbu smashed the Chinese defensive line single-handed, silencing a heavy machine-gun and decapitating five Chinese with his khukri, before falling to a bullet—but the two passes remained firmly in Indian hands.

Major General Sagat Singh’s foresight and insubordination—one can’t help wondering if Nelson was one of his heroes—had paid off. The ignominy of Thag La Ridge of ’62 had been erased. The Chinese realised that the Indian Army had come a long way since then. Further proof would come in Doklam in 2017 and in Galwan this year.

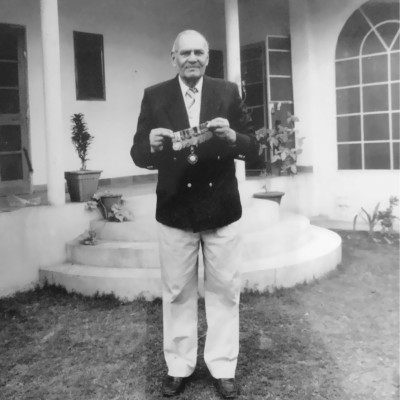

Sagat Singh did go on to greater things. As a Corps Commander in ’71 he spearheaded the march on Dhaka, with a heroic crossing of the Meghna river. In those historic surrender photographs, you will see this fabulous Rajput looming tall over General Niazi’s shoulder. Sadly he passed away a few years ago.

But all the above is merely a paraphrase, and a poor one at that. For the fuller picture, go to Probal Dasgupta’s book ‘Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten Victory Over China’. You won’t regret it.

***

PS: In 2002 my wife, younger son and I were in Sikkim on holiday. Driving to Nathu La—a tourist ‘must’ now—I was amused to see ominous signboards erected on the approach, “CAUTION: YOU ARE UNDER CHINESE OBSERVATION!” I remember thinking to myself, “Well, they can observe till kingdom come…”, but I didn’t know then that we owed Nathu La to Sagat Singh. If I had known, I would have sent him a silent but fervent salute. I repair the omission now.

Cover Picture: Nathu La (Jagran Josh)

Featured Image: (Sikkim Tourism India)